Bartolome Esteban Murillo Paintings: A Complete Guide to Murillo’s Art

Murillo paintings are some of the most beloved works of the Spanish Baroque. His soft light, tender expressions and warm colours made his religious scenes and genre pictures hugely popular in seventeenth-century Seville and across Europe. On this page you’ll find an overview of Bartolome Esteban Murillo’s life, the main themes of his art, and a curated selection of his most important paintings with links to in-depth analyses.

Who Was Bartolome Esteban Murillo?

Bartolome Esteban Murillo (baptised on 1 January 1618, probably born in late December 1617) was a leading painter of the Spanish Baroque and the dominant artistic figure in seventeenth-century Seville. He grew up in a bustling port city that was both a commercial gateway to the Americas and a deeply religious centre filled with churches, confraternities and monasteries eager for devotional images. Orphaned at a young age, he was taken in by his older sister and her husband, and it was in this environment that he began his training as a painter.

Bartolome Esteban Murillo (baptised on 1 January 1618, probably born in late December 1617) was a leading painter of the Spanish Baroque and the dominant artistic figure in seventeenth-century Seville. He grew up in a bustling port city that was both a commercial gateway to the Americas and a deeply religious centre filled with churches, confraternities and monasteries eager for devotional images. Orphaned at a young age, he was taken in by his older sister and her husband, and it was in this environment that he began his training as a painter.

Murillo’s first artistic formation took place in Seville in the workshop of Juan del Castillo, a relative and established painter. Through Castillo and the wider Sevillian milieu, he absorbed the naturalism and strong contrasts of light and shadow associated with Francisco de Zurbaran, Jusepe de Ribera and other early Baroque masters. At some point in the 1640s he probably travelled to Madrid, where he would have seen the royal collections and the work of Diego Velazquez; this encounter helped soften his palette and broaden his sense of composition. Whether or not he ever visited Italy has been debated, but his paintings show that he was well aware of both Flemish and Italian models, which arrived in Seville through trade.

His breakthrough came in the mid-1640s, when he received a major commission to paint a cycle of canvases on Franciscan themes for the convent of San Francisco in Seville. These works already display the mixture of realism and gentle spirituality that would define his mature style. Over the following decades Murillo became the most sought-after painter in the city, producing altarpieces, Immaculate Conception images, scenes from the lives of saints, and numerous variations on the Virgin and Child. At the same time, he developed a parallel line of genre scenes showing beggar boys, flower sellers and street urchins—paintings that reveal both the poverty of Seville after plague and economic decline, and the artist’s empathy for ordinary people. Many of these works were collected by foreign merchants and made their way into European collections.

In 1660 Murillo helped to found the Academy of Art in Seville (the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de Santa Isabel de Hungría) and served as one of its first leaders, shaping the training of younger artists and consolidating his status as head of the Sevillian school. By this time his style had evolved from sharper tenebrism to a softer, luminous approach in which figures seem to emerge from a vaporous, glowing atmosphere. This combination of clear storytelling, emotional warmth and refined technique made him one of the most admired painters in Spain and, later, across Europe. Murillo died in 1682 after falling from scaffolding while working on a commission in Cadiz, but his reputation as the great religious painter of his age endured for centuries, and his works remain central to any discussion of Spanish Baroque art today.

What Makes Murillo’s Paintings Unique?

Murillo’s paintings are easy to recognise because of their gentle, glowing light and softly modeled forms. Instead of using violent contrasts between darkness and brightness, he prefers a pearly atmosphere where figures seem to emerge gradually from the surrounding space. This kind of light wraps saints, children and ordinary people in the same tender radiance and gives even simple scenes a quiet sense of dignity. His religious images do not feel distant or frightening. They feel calm and approachable, as if the divine has moved closer to the viewer and taken on a human warmth.

Emotion is another key to understanding why Murillo’s paintings stand out. He does not rely on dramatic gestures or theatrical poses. Instead, he uses small, precise details in faces and hands to tell the story. A slight tilt of the head, a gentle smile, fingers pressed to the chest in devotion, or a child’s absorbed expression while playing or eating can carry the emotional weight of the whole scene. These subtle choices allow Murillo to show feelings such as tenderness, humility, playful mischief or quiet sorrow in a way that is immediately readable. Viewers may not know the full religious narrative behind a picture, but they can still understand the human emotion at its center.

Colour also plays an important role in the uniqueness of Murillo’s style. He often chooses warm, harmonious combinations of deep blues, rich reds, soft creams and golden browns. These colours help to soften the impact of harsh realities, especially in his paintings of poor children and beggars. Even when the subject is poverty, torn clothing or bare interiors, the overall mood is gentle rather than brutal. The colour harmonies and the soft transitions of light turn everyday hardship into something contemplative and almost poetic. In religious works, the same palette supports an atmosphere of serenity and comfort, making the sacred scenes feel welcoming rather than intimidating.

Murillo is distinctive as well in the way he brings together religious art and scenes of daily life. Many artists of his time focused mainly on altarpieces or mainly on genre scenes. Murillo became famous for both. His images of the Virgin and Child, the Immaculate Conception and various saints are filled with clouds, angels and flowing draperies, yet the faces and gestures feel close to real human experience. His pictures of street children, on the other hand, are grounded in sharp observation of Seville’s poorer quarters, but they are painted with the same luminous grace he uses for holy figures. As a result, the spiritual and the ordinary reflect each other. Holy figures look more human and approachable, and ordinary children receive a level of care and tenderness that gives them a quiet, almost sacred presence.

Finally, Murillo’s compositions contribute to this sense of harmony and emotional clarity. He often arranges his figures in gentle diagonals or curved groupings that guide the eye smoothly from one part of the canvas to another. Draperies, clouds, architectural frames and patches of open sky are placed so that they support the main figures without distracting from them. Empty spaces of light or shadow act like pauses in a musical phrase, giving viewers time to absorb what they see. When all these elements come together, the result is a body of work that feels balanced, humane and deeply inviting, which explains why Murillo’s paintings continue to attract and move audiences centuries after they were first created.

Famous Murillo Paintings

The Aranjuez Immaculate Conception

“The Aranjuez Immaculate Conception” is widely admired as one of Murillo’s most iconic visions of the Virgin conceived without sin, a central theme in Spanish Counter-Reformation art. The painting shows Mary rising above a crescent moon and a swirling cloud of cherubs, all bathed in Murillo’s characteristic soft, golden light. Her gentle expression, flowing drapery and the harmonious balance of blue and white helped shape how generations of believers imagined the Immaculate Conception. As a result, this work became a key reference for church decoration, devotional imagery and later painters interested in Spanish Baroque spirituality. Read the full analysis here.

The Young Beggar

“The Young Beggar” is often seen as a landmark work in Murillo’s career because it shows his early mastery of realistic genre painting. The canvas presents a poor boy quietly delousing his shirt in a shaft of light, a simple action that becomes poignant through the artist’s careful attention to pose, expression and detail. Strong contrasts between the bright foreground and dark background highlight the child’s vulnerable body and torn clothing, turning a common street scene into a powerful image of poverty and dignity. This combination of sharp observation, emotional tenderness and dramatic Baroque lighting helped make the painting one of the best known depictions of street life in seventeenth century Seville. Read the full analysis here.

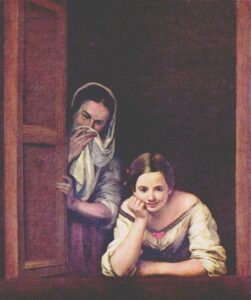

A Girl and her Duenna

A Girl and her Duenna

“A Girl and her Duenna” stands out as one of Murillo’s most engaging genre scenes, showing everyday life rather than a strictly religious subject. The painting captures a playful young woman leaning on a windowsill while her older chaperone peers out from behind, creating a lively contrast between youth and watchful propriety. Murillo’s subtle handling of expression and body language hints at flirtation and social ritual, inviting viewers to imagine the unseen street below. This blend of narrative suggestion, warm colour and intimate framing has made the work a key example of his interest in human character and social nuance. Read the full analysis here.

The Holy Family with the Little Bird

The Holy Family with the Little Bird

“The Holy Family with the Little Bird” is admired for the way Murillo turns a sacred subject into an intimate domestic scene. The Christ Child plays with a small bird on Joseph’s lap while Mary spins thread nearby, so the Holy Family appears as a loving, everyday household. The bird subtly alludes to the future Passion of Christ, adding quiet theological depth to the tender moment. Murillo’s warm light, natural poses and gentle expressions helped shape later depictions of the Holy Family as affectionate and approachable. Read the full analysis here.

Immaculate Conception of the Escorial

Immaculate Conception of the Escorial

“Immaculate Conception of the Escorial” presents the Virgin Mary rising in a golden haze of light, surrounded by clouds and cherubs, as she stands on a crescent moon. Murillo’s soft brushwork and delicate colour transitions give the scene a dreamy, weightless quality that became closely associated with his style. The painting helped establish the standard visual formula for the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception in Spain, with its youthful Virgin, flowing blue mantle and symbolic moon and stars. Because of its beauty and clarity of devotion, it became one of the most influential Marian images of the Spanish Baroque. Read the full analysis here.

Two Boys Eating a Melon and Grapes

Two Boys Eating a Melon and Grapes

“Two Boys Eating a Melon and Grapes” shows Murillo’s gift for turning an ordinary moment of street life into a vivid, engaging scene. The two ragged boys enjoy their fruit with unselfconscious pleasure, one tipping grapes into his mouth while the other clutches a melon, which makes the picture feel both humorous and tender. Strong light falls on their bare feet, torn clothes and expressive faces, highlighting the contrast between poverty and abundance. This combination of sharp realism, warm colour and affectionate observation has made the painting one of his most memorable images of Sevillian street children. Read the full analysis here.

Christ the Good Shepherd

Christ the Good Shepherd

“Christ the Good Shepherd” presents the Christ Child seated beside a lamb, turning a theological title into a tender, almost childlike image of care and protection. Murillo emphasizes the quiet bond between boy and animal through the gentle touch of Christ’s hand and the calm, trusting pose of the lamb. Soft light, pastel colours and a tranquil landscape create a peaceful mood that invites personal devotion rather than awe or fear. The painting became an enduring model for later depictions of the Good Shepherd because it combines clear religious symbolism with the emotional warmth of a childhood portrait. Read the full analysis here.

Vision of St. Anthony of Padua

Vision of St. Anthony of Padua

“Vision of St. Anthony of Padua” shows the saint kneeling in prayer as the Christ Child appears above him in a burst of light, surrounded by a host of angels. Murillo uses a strong contrast between the dark chapel interior and the radiant upper half of the canvas to emphasize the miracle. The sweeping movement of the clouds and the reaching gestures of both saint and child create a powerful sense of spiritual longing and response. This blend of dramatic Baroque lighting with tender, human emotion makes the painting one of Murillo’s most evocative depictions of a mystical vision. Read the full analysis here.

The Adoration of the Shepherds

The Adoration of the Shepherds

“The Adoration of the Shepherds” shows Murillo’s ability to turn a traditional Nativity into an intimate encounter between ordinary people and the divine. The shepherds kneel close to the Christ Child, their rough clothing and weathered faces lit by the same soft glow that surrounds Mary and the baby. This balance between humble realism and gentle radiance makes the scene feel both domestic and sacred at once. The painting became a key model for later depictions of the Nativity because it combines clear storytelling with deep warmth and human tenderness. Read the full analysis here.

The Return of the Prodigal Son

The Return of the Prodigal Son

“The Return of the Prodigal Son” highlights Murillo’s gift for telling a heartfelt biblical story through human emotion. The kneeling son clings to his father in a desperate embrace, while the older man bends over him with a mixture of sorrow, relief and forgiveness. Figures in the background watch the scene with varied reactions, turning the parable into a living drama set in an everyday street. Warm light and soft colours soften the ragged clothing and bare feet of the prodigal, emphasizing mercy and reconciliation rather than punishment. Read the full analysis here.