A Complete Analysis of “Venus Frigida” by Peter Paul Rubens

An in-depth exploration of Rubens’s 1614 “Venus Frigida,” explaining the classical motto, composition, light, color, texture, psychology, and how food and wine restore warmth to love.

An in-depth exploration of Rubens’s 1614 “Venus Frigida,” explaining the classical motto, composition, light, color, texture, psychology, and how food and wine restore warmth to love.

An in-depth exploration of Rubens’s 1614 allegory “The Triumph of the Victory,” examining composition, iconography, color, anatomy, political rhetoric, and the ethical tension between glory and its human cost.

Rubens’s 1614 “Descent from the Cross” turns the Passion into a choreography of hands, cloth, and light. Through slashing diagonals, concentrated chiaroscuro, and the unsentimental tenderness of mourners who bear Christ’s weight, the painting makes doctrine bodily and immediate, teaching viewers how grief becomes service and how love refuses to look away.

Rubens’s 1614 “The Four Evangelists” stages Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John with their traditional symbols beneath a surging red canopy. Through gestural theology, precise light, and tactile surfaces, the painting dramatizes inspiration as collaboration between human authors and divine messenger, uniting scholarship, contemplation, and proclamation in a single Baroque masterpiece.

Rubens’s 1614 “St. Sebastian” presents a bound, arrow-pierced martyr modeled with classical grandeur and Baroque tenderness. Through sculptural anatomy, dramatic light, and a storm-clearing sky, the painting transforms suffering into steadfast grace, balancing erotic tension, devotional focus, and Counter-Reformation clarity in one unforgettable male nude.

Rubens’s 1614 “The Four Continents” stages a dazzling meeting of river gods, nymphs, and emblematic animals to personify Europe, Asia, Africa, and America. Through intertwined bodies, streaming urns, a snarling tiger, and a sunlit crocodile, the painting celebrates early modern global exchange while showcasing Rubens’s mastery of flesh tones, color harmonies, and Baroque abundance.

Rubens’s 1614 “Sine Cerere et Baccho friget Venus” turns a humanist proverb into a tender riverside scene: Venus and Cupid warm themselves at a small fire as the child feeds the flame with arrows. Through luminous skin tones, complementary color harmonies, and a witty allegory linking love to food and wine, the painting argues that affection thrives where nourishment and conviviality abound.

Rubens’s 1614 “Girl with Fan” presents a poised young woman in silvery satin, pearls, and an upright fan. With supple flesh tones, controlled highlights, and a conversational three-quarter turn, the portrait transforms fashion into character, balancing Antwerp decorum with Venetian sheen.

Rubens’s 1614 “Lament of Christ” stages an intimate vigil around Christ’s body, using diagonal composition, warm chiaroscuro, and the eloquence of hands to translate grief into touch. Drapery, color, and close-knit figures turn lament into an act of love and a quiet promise of dawn.

Rubens’s 1613 “St. James the Apostle” presents the pilgrim saint in a half-length turn, gripping a travel staff and cradling a book beneath a blazing red mantle. With dramatic chiaroscuro, expressive anatomy, and a gaze that meets the viewer, the painting fuses mission, memory, and martyr-love into a single Baroque presence.

Rubens’s 1614 “The Judgment of Solomon” stages the biblical trial at its most perilous instant. With spiraling composition, radiant color, and piercing psychology, the painting links Solomon’s calm authority to the fragile life of the infant, turning a famous verdict into a public lesson on power, mercy, and truth.

Rubens’s 1613 “Sine Cerere et Baccho friget Venus” turns the Latin proverb into a swirl of bodies and harvest. Venus advances with Cupid as Bacchic and Ceres-like figures heap grapes, grain, and fruit at her feet, proving that love’s warmth is fed by bread, wine, and communal abundance.

Rubens’s 1613 “Jupiter and Callisto” captures the myth’s pivotal deception: Jupiter, disguised as Diana, coaxes the nymph in a moonlit bower while an eagle reveals his identity. Tight composition, cool–warm color contrasts, and eloquent gestures turn seduction into a lucid meditation on trust and power.

Rubens’s 1613 “Venus, Cupid, Bacchus and Ceres” turns a classical proverb into living color: without food and wine, love grows cold. Through a semicircle of luminous nudes, still-life delicacies, and hospitable gestures, the painting celebrates how grain, wine, and beauty sustain affection.

Rubens’s 1612 “Roman Charity” turns a stone cell into a sanctuary of compassion. Warm light, muscular anatomy, and restrained intimacy portray Pero nursing her shackled father, transforming a classical tale into a Baroque meditation on mercy, dignity, and embodied care.

Rubens’s 1612 “Death of Adonis,” a pen-and-wash drawing, captures Venus rushing forward to grasp her dying lover. Swift diagonals, eloquent hands, and translucent brown washes bind embrace and collapse into a single contour, revealing Baroque emotion at its most intimate and immediate.

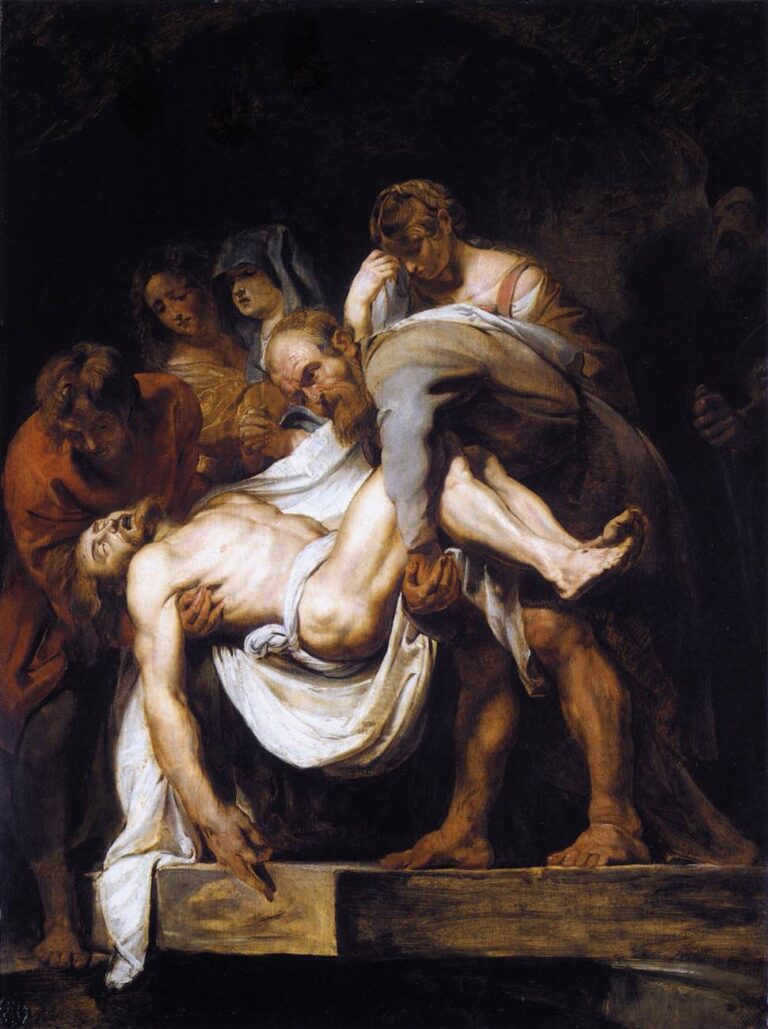

Rubens’s 1612 “The Entombment” captures the charged moment Christ is lowered onto the tomb’s slab. Sculptural anatomy, linen that shines like a spotlight, and solemn chiaroscuro turn grief into action, revealing a theology of care through straining hands, bowed heads, and the altar-like stone.

Soaring on Zeus’s eagle, Rubens’s 1612 “The Abduction of Ganymede” turns myth into Baroque spectacle. Heroic anatomy, vast black wings, celestial attendants with a golden cup, and a distant Olympian banquet create an ascending drama about desire, divine favor, and elevation to service.