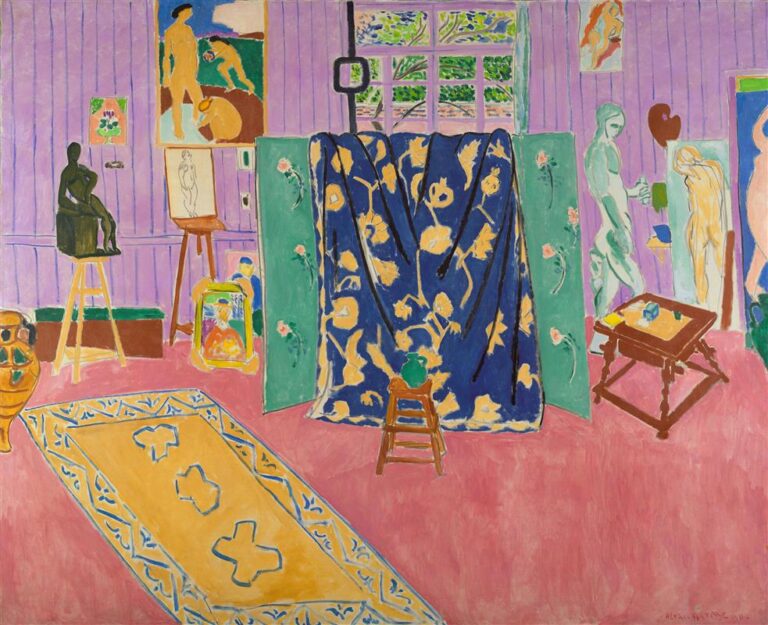

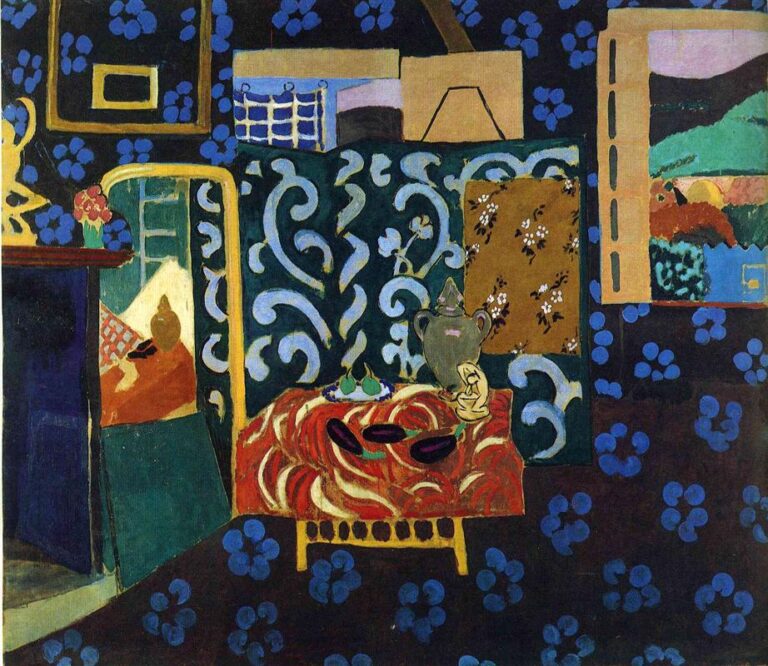

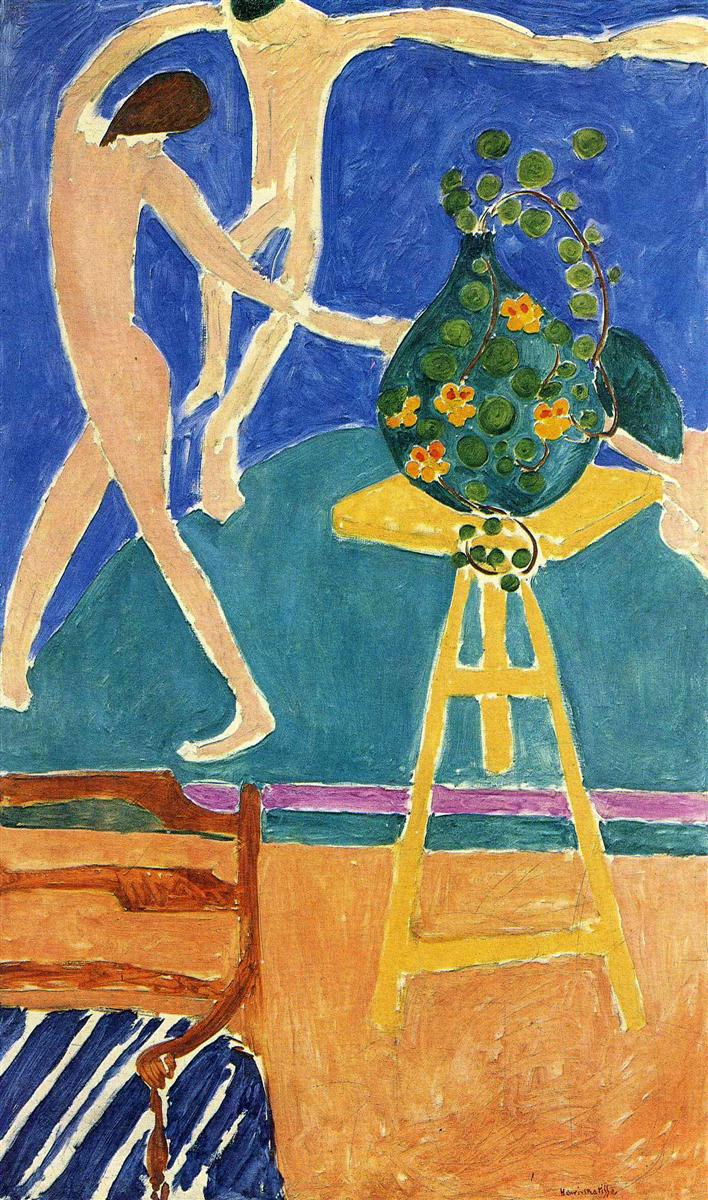

A Complete Analysis of “Nasturtiums with ‘The Dance’” by Henri Matisse

Matisse’s 1912 studio canvas stages a dialogue between a humble still life and the iconic ring of dancers from his earlier mural, weaving ultramarine, orange, and green into a seamless harmony of movement and calm. This in-depth analysis explores the painting’s color architecture, rhythmic line, and the studio as a theater of modern life.