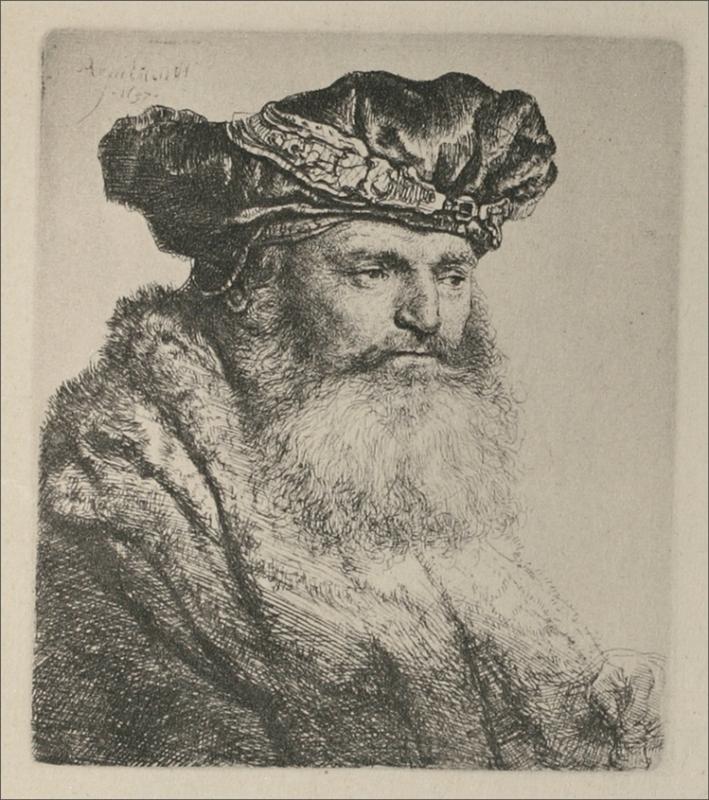

A Complete Analysis of “Polish Nobleman” by Rembrandt

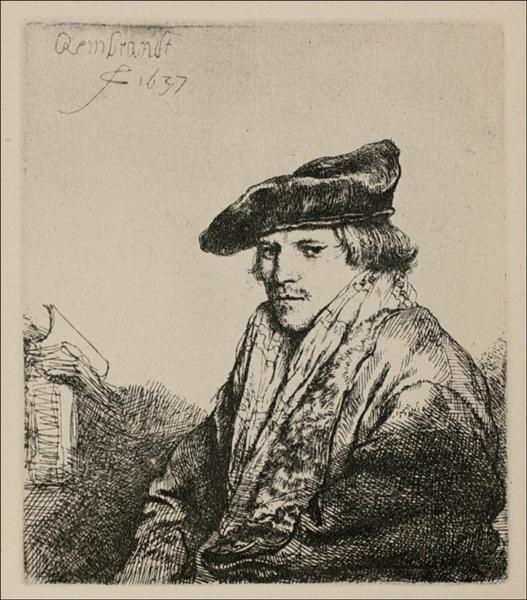

Painted in 1637, Rembrandt’s “Polish Nobleman” fuses fur, gold, and a searching gaze into a powerful tronie, using impasto highlights, smoky shadows, and a tight composition to stage authority and vulnerability in the same face.