A Complete Analysis of “In Bed” by Rembrandt

Rembrandt’s 1646 etching “In Bed” captures two lovers in a Dutch box bed beneath a heavy canopy, rendering privacy, consent, and tactile intimacy with masterful line, humane light, and everyday detail.

Rembrandt’s 1646 etching “In Bed” captures two lovers in a Dutch box bed beneath a heavy canopy, rendering privacy, consent, and tactile intimacy with masterful line, humane light, and everyday detail.

Rembrandt’s 1646 “Holy Family with a Curtain” transforms the Nativity into a private Dutch interior—Mary and the Christ Child by a hearth, Joseph at work, and a trompe-l’œil red drape that both conceals and invites—uniting intimacy, consent, and luminous chiaroscuro.

Rembrandt’s 1646 etching portrays an elderly beggar pausing with her staff, rendered in incisive lines and spacious negative ground—an intimate study of posture, texture, and dignity that turns a fleeting street encounter into a lasting human presence.

Rembrandt’s 1646 “Adoration of the Shepherds” is a glowing nocturne where a newborn’s radiance outshines lanterns, rough rafters shelter the crowd, and varied human responses—reverence, curiosity, doubt—turn the Nativity into a living study of light and community.

Rembrandt’s 1646 “Abraham Serving the Angels” turns Genesis 18 into an intimate nocturne of hospitality—three radiant angels at table, Abraham kneeling with vessels, and Sarah watching from the doorway—where light, gesture, and domestic detail carry the promise.

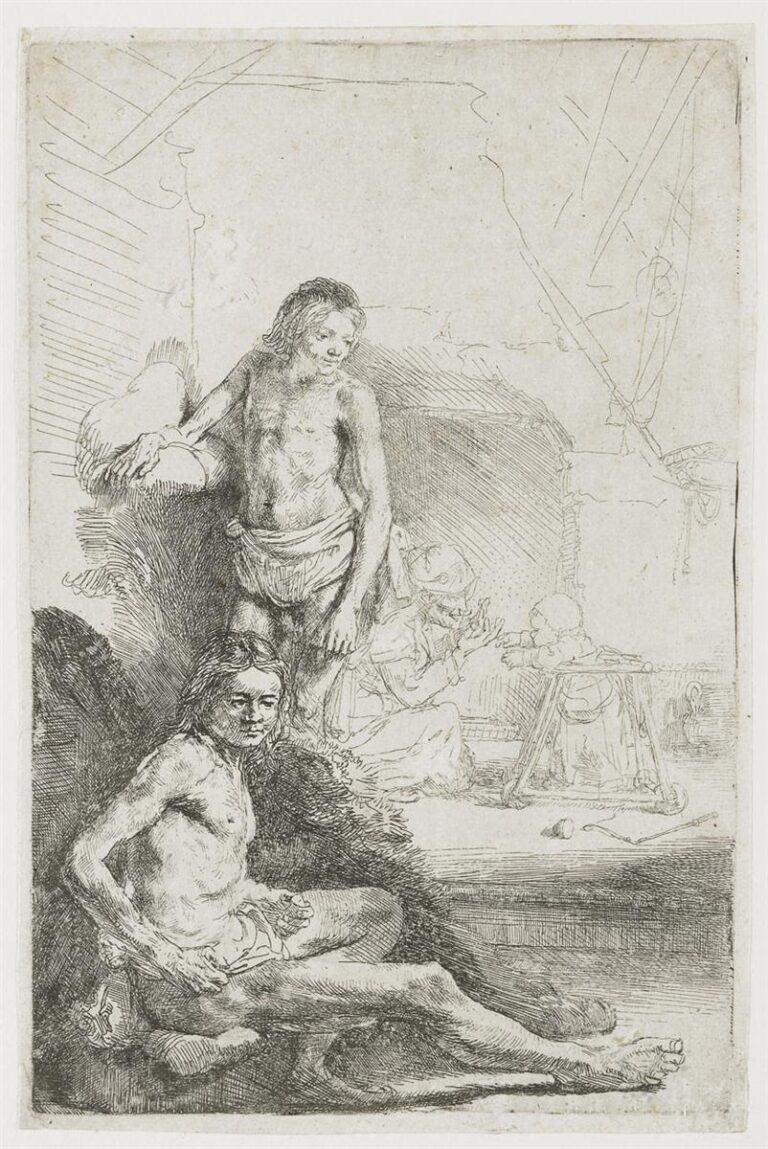

Rembrandt’s 1646 etching pairs two studies of a nude youth with a tender background scene of a mother guiding a baby in a walking frame, fusing studio practice and domestic life into a nuanced meditation on growth, light, and line.

Rembrandt’s 1645 drawing “Three Women and a Child at the Door” turns a simple threshold into a vivid social stage—three generations gathered in ink lines and wash where gesture, space, and care create an intimate drama of everyday life.

Explore Rembrandt’s 1645 “Portrait of a Young Girl”—a close, lyrical study where warm light, a coral necklace, and restrained brushwork turn a tilted head into a timeless meditation on presence and interior life.

Rembrandt’s 1645 “Woman in Bed” captures a private, lamp-lit moment as a figure parts a red curtain, revealing masterful chiaroscuro, tactile textiles, and an intimate ethics of looking that turns a bedside gesture into a meditation on presence.

Rembrandt’s 1645 drawing “Boazcast” captures Boaz pouring grain for Ruth with swift pen and wash, turning a brief scene from the Book of Ruth into a vivid study of gesture, reciprocity, and everyday mercy.

Rembrandt’s 1645 landscape “The Mill” transforms a windmill on a headland into a meditation on weather, work, and human scale—where storm and light divide the sky, figures labor at the water’s edge, and a quiet machine anchors Dutch life.

Rembrandt’s 1645 domestic drama “Tobit and Anna with the Kid” turns a brief episode from the Book of Tobit into a luminous study of trust, poverty, and conscience, using window light, hearth glow, and subtle gesture to reveal reconciliation in a humble room.

Rembrandt’s 1645 “The Holy Family” transforms sacred history into a tender domestic nocturne—Mary tending the sleeping Christ, Joseph quietly at the hearth, and soft angels aloft—uniting everyday Dutch life with luminous, empathetic chiaroscuro.

Explore Rembrandt’s 1645 etching “The Omval,” a riverside panorama on the Amstel where a gnarled tree, windmill, boats, and vast sky reveal his mastery of line, space, and everyday Dutch life.

Explore Rembrandt’s 1645 etching of a shaded boathouse and quiet brook—an intimate landscape where line, tone, and negative space turn shelter, water, and light into a lyrical meditation.

Explore Rembrandt’s 1645 oval self-portrait—an intimate study of light, texture, gaze, and mid-career self-scrutiny that turns paint into living presence.

Explore Rembrandt’s 1645 portrayal of St. Peter after his denial—an intimate etching where gesture, line, and quiet space reveal repentance turning toward hope.

Discover Rembrandt’s 1645 drawing of an elderly thinker inclined toward a book—an austere meditation on line, negative space, posture, and the quiet dignity of interior life.