Image source: commons.wikimedia.org

Albert Aublet’s Young Tunisian offers an exquisite glimpse into 19th-century Orientalist art, blending exquisite technical skill with the exotic romanticism that characterized European fascination with North Africa during the late 1800s. Created during the height of European colonial expansion, Young Tunisian stands not only as a portrait of an individual woman but as a carefully constructed cultural narrative, reflecting both the artist’s personal observations and the Western imagination’s idealized vision of the East. In this analysis, we will explore the painting’s historical background, compositional elements, artistic techniques, cultural symbolism, and its position within both Aublet’s body of work and the broader Orientalist movement.

Historical and Biographical Context

Albert Aublet (1851–1938) was a French painter known for his refined academic technique and his many contributions to the Orientalist genre. Born in Paris and trained at the École des Beaux-Arts under the prominent teacher Claudius Jacquand, Aublet inherited the academic tradition that emphasized precision, realism, and detailed finish. Like many European artists of his time, Aublet was deeply drawn to North Africa and the Middle East, regions which offered both visual inspiration and an aura of exotic mystery to Western audiences.

During the late 19th century, Tunisia—like Algeria, Egypt, and Morocco—became a favorite destination for European artists, writers, and travelers. French influence in Tunisia grew steadily, culminating in its establishment as a French protectorate in 1881. This colonial presence allowed unprecedented access for European artists to local scenes, architecture, and subjects, though always filtered through the lens of Western perspectives and biases.

Aublet traveled to Tunisia in the 1880s, and this encounter had a profound impact on his work. Young Tunisian was produced during this period of personal and artistic exploration, capturing Aublet’s fascination with the region’s people, clothing, and architecture while showcasing his academic training and sensitivity to detail.

Composition and Visual Structure

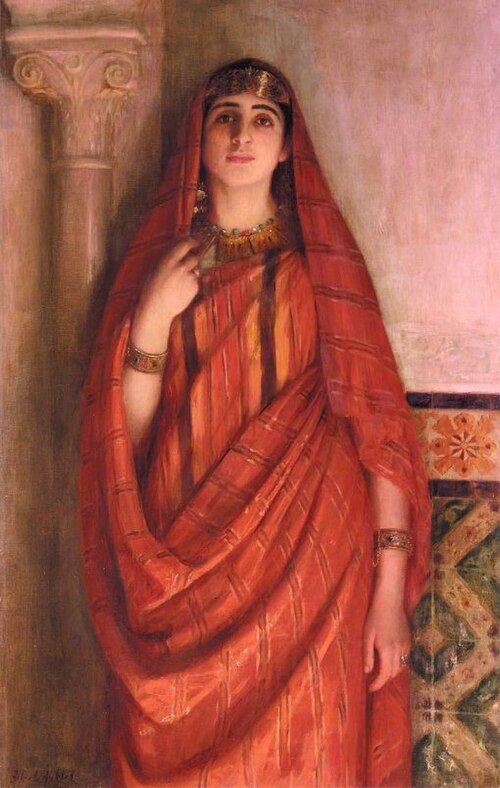

At first glance, Young Tunisian presents a straightforward portrait of a young woman standing in a quiet, dignified pose. Yet, on closer inspection, the painting reveals careful attention to composition, balance, and symbolic narrative.

The young woman stands slightly off-center against an architectural background, her full figure framed vertically by a fluted column on the left and a section of North African geometric tilework on the right. This architectural framing not only grounds her within an identifiable North African context but also lends the portrait a sense of timeless stability and order.

The verticality of the composition echoes the upright posture of the subject herself. She gazes calmly outward, engaging the viewer directly with a poised yet reserved expression. The placement of her hands is particularly expressive: one hand gently holds the edge of her flowing red garment, while the other rests delicately against her hip, fingers lightly curled. This subtle gesture conveys both grace and modesty, reinforcing the dignity of the sitter.

The controlled balance of the composition reflects Aublet’s academic training, where careful attention to proportion, pose, and balance was paramount. Nothing in the painting feels accidental; every element serves the central goal of elevating the beauty and dignity of the subject.

Use of Color and Light

Color plays a dominant role in Young Tunisian, particularly the rich, warm tones of the woman’s attire. She is wrapped in a voluminous red robe—a burnous or traditional North African draped garment—rendered with sumptuous attention to the folds and weight of the fabric. The red garment features faint horizontal stripes of gold and subtle variations in hue, creating a vibrant interplay of warm tones.

This deep red color conveys both sensual richness and cultural association, as red was often linked to ceremonial dress in North Africa. The robe’s color is skillfully offset by the softer ivory of the surrounding architecture and the earthy tones of the tiles, creating a harmonious balance that allows the figure to dominate the scene without overwhelming it.

Aublet’s handling of light is equally masterful. The soft, even illumination allows for the clear visibility of every detail while preserving a sense of intimacy. There are no harsh shadows or dramatic contrasts; instead, the light gently caresses the surfaces, emphasizing the roundness of the figure, the textures of the fabrics, and the smoothness of the column. The overall effect is one of quiet radiance, inviting contemplation rather than spectacle.

Attention to Detail

One of the most striking features of Young Tunisian is Aublet’s extraordinary attention to fine detail. Every element of the woman’s appearance is rendered with care: her jewelry, her headdress, her bracelets, and the fine patterning of her robe are all meticulously depicted.

Around her neck, she wears a golden necklace, possibly incorporating traditional Berber or North African design motifs, while her simple golden headband holds her dark hair in place. Her bracelets and rings add further elements of cultural specificity and subtle luxury. These adornments, while not ostentatious, reinforce the Orientalist fascination with exotic ornamentation and craftsmanship.

The background also reflects Aublet’s dedication to detail. The fluted column on the left hints at Islamic or Moorish architecture, while the mosaic tilework on the right displays geometric patterns typical of North African design, inspired by centuries of Islamic art that eschewed figuration in favor of abstract, mathematical beauty.

Thematic Elements and Orientalism

Young Tunisian belongs firmly within the 19th-century tradition of Orientalist painting, which portrayed Eastern cultures through the imaginative lens of European artists and collectors. This genre was characterized by a blend of genuine fascination, aesthetic admiration, and problematic exoticism.

In Orientalist art, North African and Middle Eastern subjects were often depicted as timeless, sensual, and unchanging, frequently in ways that reflected Western fantasies rather than the lived realities of the people portrayed. Young Tunisian participates in this tradition, offering Western viewers an idealized vision of the North African woman—graceful, mysterious, and adorned in beautiful fabrics and jewelry.

However, unlike some of the more eroticized or fantastical Orientalist images of harems, odalisques, or bathers, Aublet’s painting maintains a level of dignity and restraint. The young woman’s fully covered figure, her upright posture, and her calm gaze suggest self-possession rather than objectification. This more respectful approach distinguishes Young Tunisian from many of its contemporaries.

Nonetheless, the painting cannot be fully divorced from its colonial context. The act of portraying and consuming images of “the exotic other” served to reinforce the power imbalance between colonizing nations and their subjects. The portrayal of cultural difference was often simplified and romanticized, flattening the complexities of Tunisian society into easily digestible visual tropes.

Aublet’s Artistic Style

Albert Aublet’s artistic style embodies many of the values of French academic art: technical mastery, attention to form, and polished execution. Unlike the avant-garde movements gaining ground in Paris at the time—Impressionism, Symbolism, and Post-Impressionism—Aublet remained rooted in the classical traditions of portraiture and genre painting.

His smooth, detailed brushwork, careful modeling of form, and balanced compositions reflect the training and ideals of the École des Beaux-Arts. However, Aublet’s Orientalist subjects allowed him to explore a richer palette, more elaborate textures, and distinctive cultural motifs that might not have been permissible in purely academic historical or mythological painting.

In Young Tunisian, Aublet demonstrates both his academic discipline and his sensitivity to the visual richness of North African culture. His portrayal avoids caricature and invites admiration for the subject’s poise and elegance, even as it participates in the broader Orientalist genre.

Gender and Representation

The representation of women in Orientalist art has been the subject of extensive critical analysis, particularly regarding the ways in which European male artists projected their fantasies onto female subjects from colonized cultures. In many Orientalist works, women were depicted in various states of undress, within imagined harems or baths, serving Western fantasies of Eastern sensuality and availability.

Young Tunisian offers a more restrained and respectful portrayal. The woman’s body is fully covered in rich, voluminous fabric; her jewelry is elegant but modest; her expression is contemplative rather than inviting or submissive. Rather than presenting her as an object of desire, Aublet positions her as a subject of beauty and cultural dignity.

Still, the painting must be understood within its context: a European male artist portraying a colonized woman for a Western audience. Her carefully staged pose, the selection of exotic costume, and the architectural setting all contribute to the creation of a scene designed to satisfy Western curiosity about North African life—filtered, stylized, and idealized.

The Influence of Tunisia and North Africa

Aublet’s travels to Tunisia deeply informed his artistic output. For European artists of the 19th century, North Africa offered both visual and cultural experiences that felt radically different from the familiar landscapes and customs of Europe. The vibrant markets, colorful textiles, architectural ornamentation, and intense Mediterranean light all provided rich material for painting.

In Young Tunisian, Aublet captures several of these elements with precision and sensitivity. The drapery of the burnous reflects the artist’s study of Tunisian textiles; the architectural background echoes local design motifs; and the soft, glowing light suggests the unique luminosity of the Mediterranean sun.

For French audiences in the 1880s and 1890s, such paintings offered both an escape into the exotic and a subtle reinforcement of their own national identity as colonial overseers of these foreign lands. Aublet’s work thus served as both aesthetic pleasure and cultural documentation within the imperial imagination.

Legacy and Contemporary Reflection

Albert Aublet’s Young Tunisian remains a striking and beautiful example of late 19th-century Orientalist art. Its technical finesse, compositional grace, and cultural detail continue to attract admiration from art historians and collectors.

However, contemporary viewers and scholars increasingly approach Orientalist paintings with a critical awareness of their complex historical context. Works like Young Tunisian exist at the intersection of genuine artistic admiration and the unequal power dynamics of colonialism. They reflect both the curiosity and the control that European artists exercised over the representation of non-European peoples.

In today’s globalized art world, Aublet’s painting can be appreciated both for its beauty and for the conversations it provokes about cultural representation, power, and historical memory.

Conclusion

Young Tunisian by Albert Aublet stands as a masterful blend of academic technique, cultural fascination, and artistic sensitivity. Through its elegant composition, rich color palette, and attention to detail, the painting embodies many of the strengths and contradictions of Orientalist art.

While it offers a dignified and restrained portrayal of its subject, it remains a product of its time—a window into both the European romanticization of North Africa and the technical excellence of 19th-century French academic painting. Today, Young Tunisian invites viewers not only to admire its beauty but to reflect on the historical and cultural forces that shaped its creation.

By engaging deeply with both the aesthetic qualities and the broader historical context of the painting, we gain a fuller appreciation of its complexity and its lasting significance within art history.