Image source: commons.wikimedia.org

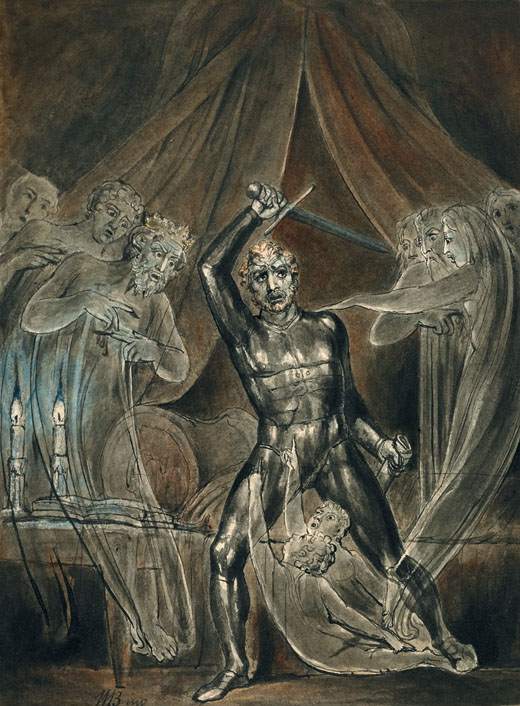

In the vast and mysterious world of William Blake (1757–1827), few works better capture his unique vision than Richard III and the Ghosts. Painted around 1806, this haunting image brings together Shakespearean drama, psychological terror, spiritual symbolism, and Blake’s singular visual language.

As one of the most original figures of British Romanticism, Blake defies traditional classification. He was poet, mystic, painter, and engraver — a visionary whose art sought to unveil the unseen worlds of imagination, spirituality, and human conscience. In Richard III and the Ghosts, Blake interprets one of Shakespeare’s most chilling moments: the king’s haunted vision on the eve of the Battle of Bosworth Field.

This in-depth analysis will explore Blake’s artistic choices, symbolic content, historical background, and lasting impact.

The Literary Source: Shakespeare’s Richard III

Blake’s painting draws directly from Shakespeare’s play “Richard III,” Act V, Scene III. On the eve of battle, King Richard is visited in his dreams by the ghosts of his many victims, who curse him and bless his enemy, Henry Tudor.

The ghosts include:

King Henry VI

Prince Edward

Clarence (Richard’s brother)

Lord Hastings

The Princes in the Tower

Lady Anne (Richard’s wife)

Buckingham

The scene is one of Shakespeare’s most psychologically intense moments — a confrontation with guilt, remorse, and the inevitability of Richard’s downfall.

Blake’s painting does not depict the full cast of ghosts, but rather distills the emotional core of the scene: Richard’s internal torment as the weight of his crimes crushes him.

The Composition: A Theater of the Mind

Central Figure: Richard III

At the heart of the painting stands Richard III, frozen in a moment of terror and defiance:

He raises a sword, as if to strike at the phantoms that surround him.

His body is tense, muscular, and almost statuesque.

His facial expression blends fear, rage, and desperation.

Richard is caught between:

Self-defense and helplessness

Defiance and psychological collapse

Physical power and moral impotence

His armored form becomes not only a defense against battle, but a symbolic shell attempting to protect him from the consequences of his own conscience.

The Ghosts

Surrounding Richard are the spectral forms of the murdered:

Their faces are pale, hollow-eyed, and ethereal.

Some point accusingly; others appear sorrowful.

They float in draped, almost otherworldly garments.

Their presence is both accusatory and spiritual — representing Richard’s sins made manifest.

The Setting

The background is dominated by:

A darkened chamber, perhaps his tent.

Heavy red drapery, giving the scene a theatrical and claustrophobic atmosphere.

Two burning candles placed on either side, symbolizing life and death, hope and doom.

The use of limited space enhances the sense that Richard is trapped not by physical enemies but by his own mind.

Light and Color: The Drama of Chiaroscuro

Blake uses stark contrasts of light and dark to heighten the scene’s emotional intensity:

The pale ghosts are illuminated from within, glowing with a cold, spectral light.

Richard himself is painted in darker tones, emphasizing the weight of guilt and fear.

The background is rich in deep browns and reds, enhancing the sense of oppressive atmosphere.

The only warmth comes from the flickering candle flames, suggesting flickering life and unstable fate.

Blake’s limited color palette focuses attention on spiritual conflict rather than physical reality.

Psychological Depth: The Inner Nightmare

While Shakespeare’s scene unfolds in Richard’s dream, Blake makes the psychological dimension fully explicit:

The ghosts do not simply appear; they seem to emerge from Richard’s mind, manifesting as projections of his inner torment.

Richard’s raised sword is not simply self-defense but a futile gesture against his own conscience.

The absence of any battlefield elements or physical action reinforces that this is a visionary struggle.

Blake visualizes not only the external plot but the invisible spiritual battle for Richard’s soul.

Symbolism: The Moral Universe of William Blake

Blake was deeply influenced by his personal spiritual philosophy, which combined elements of:

Christian mysticism

Gnostic thought

Personal mythology

Radical morality

Within this framework, Richard III and the Ghosts becomes not only a Shakespearean illustration but a spiritual allegory.

Richard as the Fallen Man

His armored, muscular body recalls Blake’s recurring figure of the Fallen Man — a symbol of human pride, separation from divine love, and enslavement to material power.

Richard’s rise to power through deceit and murder reflects Blake’s view of spiritual corruption through worldly ambition.

The Ghosts as Divine Judgment

The ghosts function not simply as spirits of the dead but as manifestations of divine law.

They represent the moral balance that Blake believed governed the universe — sins must be accounted for, and inner corruption ultimately consumes the guilty.

The Swords and Gestures

Richard’s upraised sword may symbolize the futility of violence against spiritual forces.

The ghosts’ pointing fingers echo accusation, prophecy, and judgment.

Artistic Techniques: Blake’s Unique Visual Language

Unlike most painters of his time, Blake:

Combined watercolor, ink, and tempera techniques.

Used fine line work from his background as an engraver.

Preferred flat planes of color with minimal modeling.

Created highly stylized, visionary compositions rather than naturalistic scenes.

In Richard III and the Ghosts, this results in:

Ethereal, transparent ghosts that seem to float between worlds.

Strong contour lines defining every figure.

Symbolic rather than realistic space and perspective.

Blake’s deliberate rejection of traditional painterly techniques allows his work to operate in a mythic, dreamlike register.

Blake's Broader Engagement with Shakespeare

Blake illustrated numerous scenes from Shakespeare, including:

Macbeth (The Three Witches)

King Lear (Cordelia and Lear)

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

In all these works, Blake:

Focused on spiritual and psychological themes rather than theatrical realism.

Found in Shakespeare’s plays a mirror of his own mystical and moral concerns.

Saw Shakespeare not just as a playwright but as a kindred visionary exploring the battle between innocence and corruption, spirit and matter.

Richard III and the Ghosts is one of his most successful Shakespearean interpretations for its pure concentration of guilt, terror, and divine judgment.

The Romantic Context

Blake’s work belongs firmly to the Romantic movement, which emphasized:

Intense emotion

Individual moral struggle

The supernatural

Rebellion against classical order

Where many Romantics (e.g. Delacroix, Géricault, Friedrich) explored these themes through large-scale oil paintings, Blake explored them through his intimate, highly personal visual and poetic world.

Richard III and the Ghosts exemplifies the Romantic fascination with the subconscious, foreshadowing later explorations of psychological interiority in art.

Reception and Legacy

In Blake’s lifetime, his work was largely misunderstood or ignored. His highly idiosyncratic style was:

Too visionary for the academic art world.

Too symbolic for mainstream taste.

Too private for the public marketplace.

However, by the late 19th and 20th centuries, Blake came to be recognized as:

A founding figure of visionary Romantic art.

A precursor to Symbolism, Surrealism, and psychological modernism.

One of Britain’s most original cultural voices.

Richard III and the Ghosts is now viewed as a masterpiece of spiritual illustration, merging literature, morality, and psychological insight.

Comparison with Other Depictions of Richard III

Many artists have portrayed Richard III, usually emphasizing:

His physical deformity (as described by Shakespeare).

The battlefield drama of Bosworth.

The political intrigue of his rise and fall.

Blake, in contrast, strips away historical detail and focuses entirely on the moral and spiritual essence of the character. There are no soldiers, tents, or external enemies — only the king facing his own inner collapse.

In this way, Blake’s version is one of the most profoundly psychological depictions of Richard III ever created.

Conclusion: The Power of Visionary Conscience

Richard III and the Ghosts (c. 1806) by William Blake stands as a profound visual meditation on:

The destructive power of ambition.

The inescapable force of conscience.

The spiritual consequences of evil deeds.

The ultimate judgment that awaits all human souls.

Through his singular vision, Blake transforms Shakespeare’s scene into a universal allegory of guilt, terror, and moral reckoning, rendered with an artistic language that is uniquely his own.

Even today, more than two centuries after its creation, Blake’s painting continues to haunt viewers with its combination of psychological realism and visionary mysticism, reminding us of the eternal struggle between light and darkness that plays out within every human heart.