Image source: commons.wikimedia.org

The Fairytale Witch II (Die Märchendrude II), painted by Paula Modersohn-Becker, is one of the most intriguing and psychologically rich works of early 20th-century German modernism. Created during a period of personal and artistic transformation, the painting combines elements of symbolism, primitivism, and expressionism, reflecting the artist’s unique vision and the broader cultural shifts of her time. In this in-depth analysis, we will explore the historical context, composition, color usage, symbolism, psychological depth, and lasting significance of this mysterious and haunting work.

Historical Context: The Emergence of German Modernism

Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876–1907) was a pioneering figure in early modern art, particularly within Germany’s avant-garde scene. She was a key member of the Worpswede artists’ colony, which sought to escape the pressures of urban industrial life and find inspiration in rural simplicity and nature. While many of her male contemporaries focused on landscapes and scenes of peasant life, Modersohn-Becker’s art was deeply personal, frequently centering on women, motherhood, and the cycles of life.

At the turn of the 20th century, German art was undergoing a major transition. While Paris remained the center of modern innovation, Germany was developing its own modernist voice through movements like Expressionism, Symbolism, and Jugendstil (Art Nouveau). Modersohn-Becker’s work stands at the intersection of these currents, blending German romanticism, French post-impressionism, and her own instinctive primitivism.

Painted near the end of her brief life, The Fairytale Witch II reflects Modersohn-Becker’s increasingly experimental approach and her deep engagement with themes of myth, femininity, and mortality. The painting draws on German folklore and fairy tale tradition while simultaneously subverting and reinterpreting these cultural archetypes.

Composition: A World of Symbolic Tension

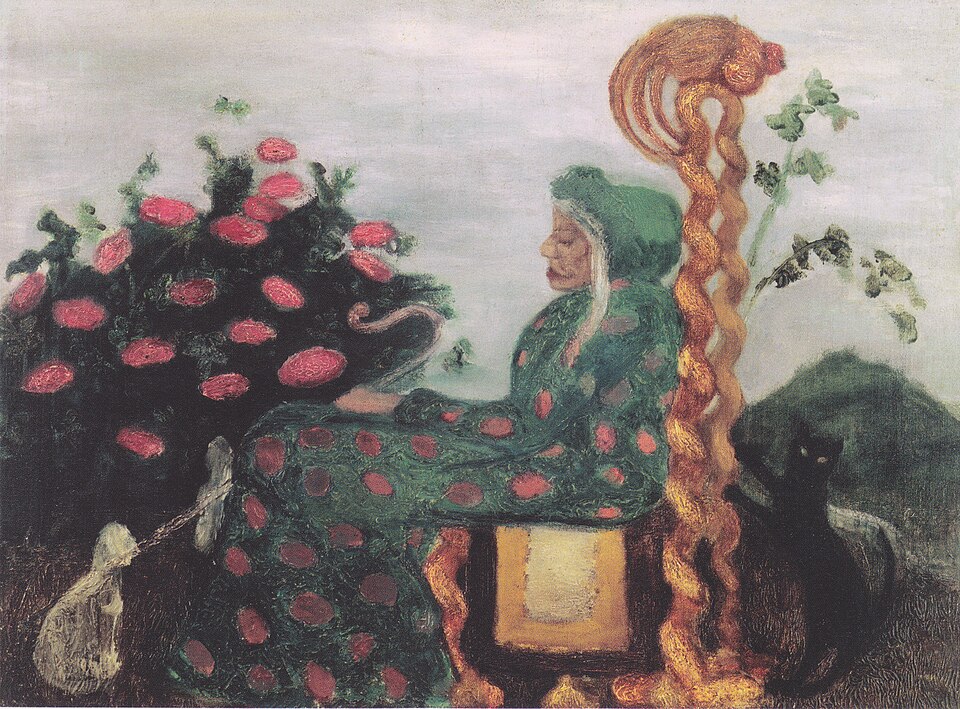

The composition of The Fairytale Witch II is deceptively simple but loaded with symbolic meaning. The central figure—a seated elderly woman—is shown in profile, her long, exaggerated braid curling unnaturally down from the elaborate golden chair that frames her. Her face is closed, her eyes cast downward in contemplation or perhaps resignation.

Behind her, a large bush blooms with oversized, vividly pink flowers, adding a surreal, dreamlike quality to the scene. A black cat sits beside her chair, its piercing yellow eyes directly meeting the viewer’s gaze, introducing an element of mysticism and unsettling presence. On the lower left, a chained animal—likely a goat—appears subdued, its ambiguous form adding further symbolic depth.

Unlike traditional portraiture that aims to flatter or document, Modersohn-Becker presents a world of inner tension and ambiguity. The flat, compressed space reinforces the psychological unease, as if the entire scene exists in a timeless, mythic space outside of everyday reality.

Color Palette: Earthy Symbolism and Emotional Contrast

Modersohn-Becker’s color choices are deliberate and symbolic. The earthy green tones of the woman’s robe dominate the foreground, covered with circular, blood-red spots that stand out like ritualistic symbols. These patterns echo the blooming flowers in the background, linking nature, fertility, and possibly danger or sacrifice.

The muted sky is painted in pale, washed-out shades of grey-blue, creating a sense of isolation and distance. The chair’s golden hues introduce a royal, almost sacred quality to the scene, while also visually contrasting with the surrounding somber colors. The black cat and chained goat introduce darker, shadowy tones that suggest forces of control, submission, or hidden power.

Rather than using color to describe light and natural appearance, Modersohn-Becker applies it symbolically to communicate mood, emotional undertone, and spiritual significance. The overall palette oscillates between life-affirming vitality (seen in the flowers and gold) and ominous darkness (seen in the chained animal and black cat).

Brushwork and Technique: Primitivist Expression

Modersohn-Becker’s brushwork in The Fairytale Witch II is highly characteristic of her late period. The surface is textured, with visible strokes that suggest both deliberation and spontaneity. The forms are simplified, almost childlike, recalling the influence of early Renaissance frescoes and African and Oceanic art, which were gaining attention in European avant-garde circles at the time.

The simplified anatomy, flattened spatial depth, and absence of intricate detail reflect Modersohn-Becker’s embrace of primitivism—a reaction against academic realism and the polished aesthetic of the 19th century. This intentional naivety allows her to focus on the psychological and symbolic resonance of the scene rather than getting lost in external appearances.

This technique imbues the painting with a raw, almost ritualistic energy, as if viewers are witnessing a fragment from an ancient, half-forgotten myth.

Symbolism and Interpretation: The Witch as Archetype

At the heart of The Fairytale Witch II is the archetype of the witch—a figure deeply embedded in European folklore, often representing both wisdom and danger, fertility and destruction. In German tradition, witches were both feared and revered as custodians of secret knowledge, natural remedies, and feminine power that operated outside patriarchal structures.

Modersohn-Becker’s witch is not presented as grotesque or malevolent, but rather as solemn, introspective, and quietly powerful. The elongated braid, flowing like liquid gold, suggests a link to vitality, fertility, and perhaps the life force itself. Hair has long been associated with power and sexuality in myth, and its exaggerated presence here emphasizes its importance.

The chained goat may represent submission, domestication of wild instincts, or sacrificial ritual. Goats are also historically linked with pagan fertility rites and the devil, adding multiple layers of meaning. The black cat, traditionally linked to witchcraft and feminine intuition, becomes both a companion and an ambiguous symbol of the otherworldly.

The flowers bursting behind the woman symbolize life, growth, and perhaps even resurrection. Yet their exaggerated, oversized forms create a slightly surreal atmosphere, reinforcing the painting’s fairy-tale unreality.

Psychological Depth: Femininity, Isolation, and Mortality

One of the most compelling aspects of The Fairytale Witch II is its psychological complexity. Modersohn-Becker’s paintings often explore themes of femininity not through idealized beauty but through cycles of aging, fertility, motherhood, and solitude.

The seated woman may represent both an individual and an archetype of the aging female body—an uncommon and even radical subject in an art world dominated by youthful nudes and male fantasies. In this sense, Modersohn-Becker aligns herself with the symbolic exploration of female experience, confronting the viewer with a rarely acknowledged dimension of womanhood.

The painting’s quiet isolation reflects Modersohn-Becker’s own life struggles. As a female artist navigating both personal and professional ambitions at a time when women were marginalized in the art world, she often experienced profound solitude. This tension between inner power and external limitation permeates the painting, offering a deeply personal reflection on autonomy, aging, and mortality.

Influences: German Romanticism, Symbolism, and Early Expressionism

While Modersohn-Becker’s work is often associated with the Worpswede colony, her broader influences are equally important in understanding The Fairytale Witch II. German Romanticism, with its emphasis on nature, folklore, and the sublime, provided a cultural backdrop for much of her generation.

She was also influenced by Symbolist painters such as Odilon Redon and Puvis de Chavannes, who explored dreams, spirituality, and myth through simplified forms and otherworldly atmospheres. Like Redon, Modersohn-Becker rejected literal representation in favor of suggestion and psychological depth.

The work also prefigures the Expressionist movement that would soon flourish in Germany. Groups such as Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter would carry forward similar interests in bold color, primitivism, and emotional directness, though Modersohn-Becker’s art remains more introspective and intimate than much of Expressionism’s extroverted energy.

Paula Modersohn-Becker’s Legacy: A Pioneer of Female Modernism

Paula Modersohn-Becker’s career was tragically short; she died in 1907 at the age of 31, shortly after giving birth to her first child. Yet in that brief time, she created a groundbreaking body of work that anticipated many of the central concerns of 20th-century art.

Her exploration of female identity, psychological depth, and symbolic language positioned her as one of the first truly modern female artists. Unlike many of her contemporaries, she painted women not as passive objects but as full participants in the human experience, with agency, dignity, and complexity.

The Fairytale Witch II encapsulates this legacy. It is a haunting, deeply original work that refuses easy interpretation, inviting viewers into a symbolic world that blends personal narrative, cultural mythology, and universal themes of life, power, and transformation.

Enduring Significance: A Feminist and Modernist Milestone

Even today, The Fairytale Witch II resonates with contemporary viewers. Its mysterious, layered imagery continues to spark discussions about femininity, aging, and the human psyche. As interest in early female modernists grows, Modersohn-Becker’s work has been increasingly recognized for its originality and quiet radicalism.

The painting’s ambiguous symbols allow it to transcend time and culture, functioning almost like a visual poem that invites multiple readings. Is the woman a sorceress, a healer, a prisoner, or a queen? Is the chained animal a symbol of sacrifice or domesticated power? Modersohn-Becker offers no clear answers, trusting the viewer to confront their own interpretations.

In this way, The Fairytale Witch II embodies the best of modernist experimentation: it disrupts convention while remaining deeply human, intimate, and emotionally rich.

Conclusion: A Haunting Masterpiece of Inner Power

The Fairytale Witch II stands as one of Paula Modersohn-Becker’s most captivating achievements. Through its primal symbolism, muted yet charged color palette, and dreamlike composition, the painting invites us into a world where myth and reality blur, where personal and collective narratives converge.

In her short life, Modersohn-Becker redefined the possibilities of modern art, opening space for women’s voices, experiences, and inner worlds to enter the canon of serious artistic inquiry. Her work remains a touchstone for modern feminist art history and a profound statement on the complexities of life, aging, and feminine strength.

For any art lover or scholar, The Fairytale Witch II offers not just visual beauty, but a portal into the deeper currents that shaped early modernism—a haunting reminder of how personal vision can transcend both time and biography to become universal.