Image source: commons.wikimedia.org

Few 19th-century American painters captured the spiritual resonance of landscape as powerfully as George Inness. His 1870s painting Saco Valley stands as a masterful example of his mature style, combining technical refinement, emotional subtlety, and deeply personal philosophical meaning. With its soft atmospheric tones, luminous light, and tranquil pastoral setting, Saco Valley embodies both the aesthetic and spiritual ideals that defined Inness’s lifelong pursuit to represent not just nature, but nature’s unseen essence.

George Inness (1825–1894) occupies a central place within American landscape painting. While many of his early works reflect the influence of the Hudson River School, known for its grand, heroic vistas, Inness gradually moved away from that tradition toward a more intimate, tonally subtle approach. His mature paintings balance careful observation of nature with an inner vision shaped by the ideas of Swedenborgian mysticism, which taught that the natural world served as a visible representation of spiritual realities. Inness did not simply paint trees, skies, and fields; he painted the divine order he perceived within them.

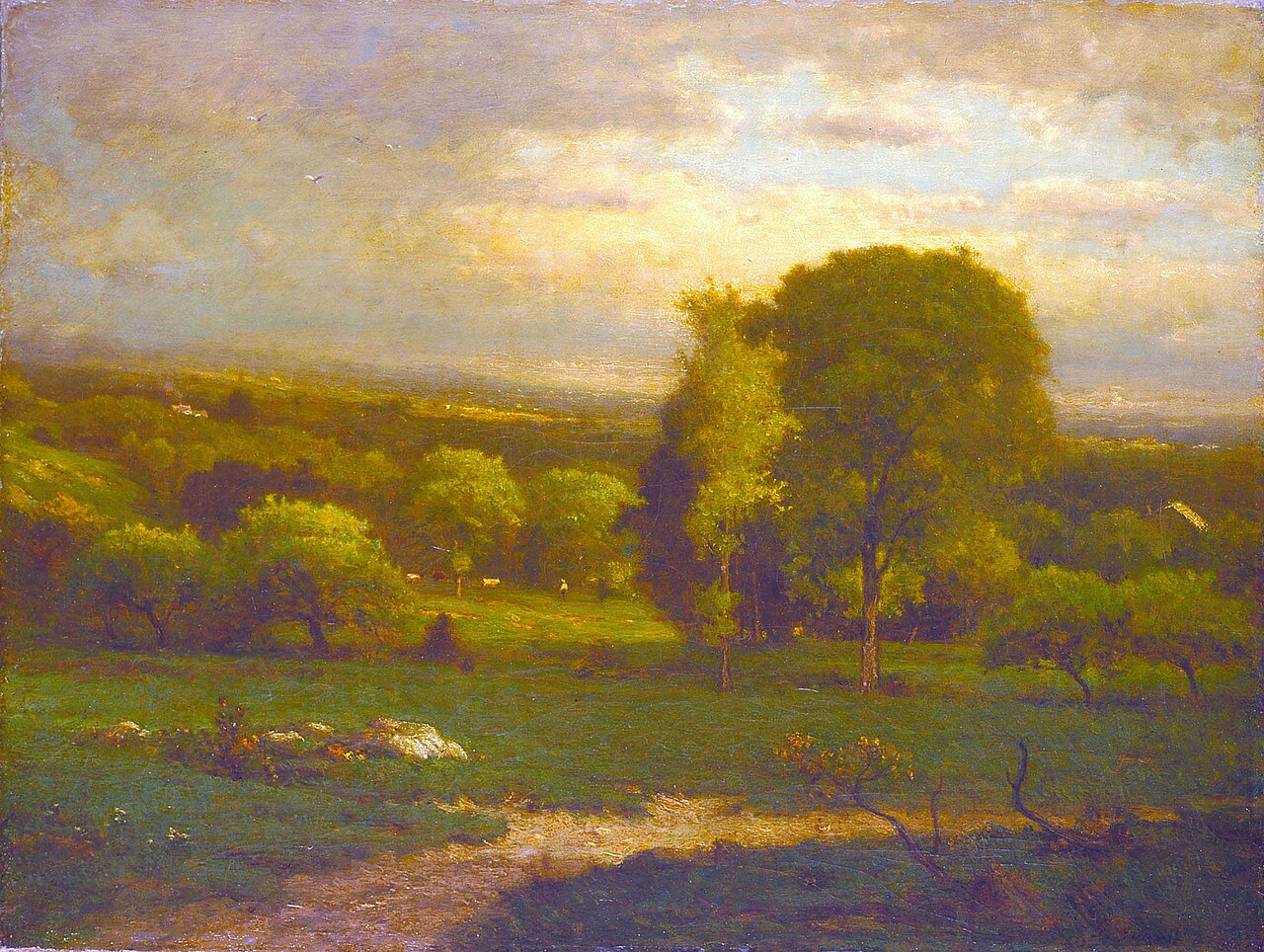

Saco Valley captures a quiet moment of pastoral serenity. The scene unfolds gently, offering a harmonious blend of open fields, distant rolling hills, and luminous sky. The landscape is suffused with a soft, golden light that seems to emanate from within the scene itself rather than from an external source. This radiance bathes the foliage in subtle warm tones, blending greens, golds, and soft purples into a seamless atmospheric whole. The painting does not seek to overwhelm the viewer with dramatic contrasts or monumental scenery but instead invites contemplation and stillness.

At the heart of the composition stands a large, full tree, dominating the foreground while maintaining a graceful balance with its surroundings. Its dark, solid form anchors the scene and draws the eye forward, while the smaller trees scattered throughout the middle ground create a sense of depth without rigid perspective. The tree’s irregular edges blur gently into the ambient light, illustrating Inness’s mastery of dissolving form into atmosphere. Behind this central cluster, the valley unfolds into receding fields and wooded hills, fading gradually into the horizon beneath a cloud-filled sky.

The sky itself is a marvel of tonal painting. Unlike the clear blue skies typical of many Hudson River School landscapes, Inness opts for a hazier, more diffuse atmosphere. Soft layers of clouds hover in varying shades of cream, lavender, and muted blue, reinforcing the painting’s overall mood of quiet introspection. This atmospheric subtlety creates a sense of infinite space while preserving an intimate connection to the immediate landscape. The sky does not merely serve as a backdrop but participates fully in the emotional tenor of the scene.

One of Inness’s great strengths in Saco Valley lies in his ability to convey mood through restrained color. The painting’s limited palette enhances its unified effect, blending warm earth tones, muted greens, and soft pastels into a harmonious visual field. The gentle diffusion of color fosters a contemplative calm, inviting the viewer to linger and absorb the painting’s quietude. Inness avoids sharp contrasts, allowing the entire scene to breathe as a single living organism.

Throughout Saco Valley, Inness’s brushwork reflects his commitment to suggestion over description. Close inspection reveals that many of the trees and grasses are rendered with minimal, almost abstract strokes. Rather than laboring over every leaf or blade of grass, Inness suggests form through soft transitions of tone and texture. This technique allows the viewer’s eye to complete the image, engaging the imagination and creating a more personal experience of the landscape. The viewer is not presented with a meticulously detailed topography but rather with an impression of nature’s underlying unity.

While Saco Valley offers no grand narrative, its spiritual undercurrents are profound. Inness was deeply influenced by the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg, an 18th-century Swedish mystic whose theology emphasized the correspondence between the material and spiritual worlds. For Inness, nature was not merely scenery but a living testament to divine order. The gentle rhythms of trees, fields, and clouds in Saco Valley reflect this belief in a higher, unseen harmony governing all things. The painting becomes a visual prayer, a meditation on the sacredness of nature’s rhythms and forms.

Historically, Saco Valley belongs to a period in American art when landscape painting was undergoing a significant transformation. Earlier 19th-century American painters such as Thomas Cole, Frederic Church, and Albert Bierstadt presented grand, theatrical vistas that celebrated the sublime power of wilderness and Manifest Destiny. In contrast, Inness and his contemporaries in the so-called “Tonalist” movement embraced a more intimate, poetic vision of the American landscape. Tonalism favored muted colors, atmospheric effects, and quiet moods over grandeur and spectacle. Inness’s work played a foundational role in defining this shift.

Inness’s move away from strict topographical accuracy also marked an important break from the prevailing realism of earlier American landscape traditions. Rather than providing a precise map of Saco Valley’s geographical features, Inness abstracts and simplifies the scene, prioritizing mood and harmony over faithful documentation. The result is a landscape that feels both specific and universal, rooted in a particular place yet resonant with broader emotional and spiritual meaning.

The setting of Saco Valley itself adds another layer of resonance. The Saco Valley region, stretching through parts of New Hampshire and Maine, was a favored destination for American painters seeking inspiration from New England’s varied natural beauty. Its rolling hills, meandering rivers, and soft light offered an ideal subject for artists interested in capturing both the physical beauty and the psychological mood of the landscape. For Inness, Saco Valley provided not only a site of visual interest but a sanctuary for his spiritual meditations.

The emotional impact of Saco Valley lies in its ability to suggest both permanence and transience. The sturdy trees, the enduring fields, and the long horizon evoke the timelessness of the earth, while the fleeting light and gently moving clouds remind us of the ephemeral nature of individual moments. This duality reflects Inness’s own philosophical contemplation of time, change, and the eternal.

Inness’s mature style, as seen in Saco Valley, also reflects his increasing emphasis on what he called “the subjective element” in art. For him, painting was not about copying nature but about expressing one’s internal response to it. In this sense, Saco Valley is not simply a record of external forms but a translation of Inness’s personal experience of standing before the valley, feeling its light, air, and spiritual presence. The painting thus becomes a bridge between outer world and inner state, inviting viewers to enter into a shared contemplative experience.

While Saco Valley may lack the dramatic vistas that characterize some of Inness’s earlier or more commercially popular works, it achieves a depth of feeling that rewards careful viewing. The more one studies the painting, the more its subtleties reveal themselves: the faint glow along the horizon line, the barely suggested distant trees, the interplay of shadow and reflection on the ground. These quiet details accumulate to create a powerful sense of stillness and unity, drawing the viewer into a state of meditative absorption.

In the broader context of American art history, George Inness stands as a bridge between the grandeur of the Hudson River School and the modernist innovations that would follow in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His tonal approach laid groundwork not only for American Tonalism but also for later developments in Impressionism and abstract landscape painting. Inness’s emphasis on mood, atmosphere, and personal vision anticipates many of the concerns that would occupy later modern artists.

Saco Valley remains an exemplary statement of Inness’s artistic and spiritual philosophy. It invites viewers not to marvel at nature’s grandiosity but to find peace and transcendence in its gentle harmonies. The painting functions almost as a visual hymn—quiet, reverent, and profound. It asks its audience to slow down, to look beyond surface appearances, and to recognize the deeper currents of life flowing through the natural world.

In conclusion, Saco Valley by George Inness stands as a masterwork of American tonal landscape painting. Its quiet luminosity, restrained color, and soft atmospheric treatment reveal an artist at the height of his powers, blending technical mastery with profound spiritual insight. Inness’s ability to evoke both the physical and metaphysical qualities of the landscape elevates Saco Valley beyond mere depiction into the realm of poetic meditation. The painting endures as a timeless invitation to contemplate the sacred rhythms of nature and to experience, if only for a moment, the peace that lies at the heart of the world.