Image source: commons.wikimedia.org

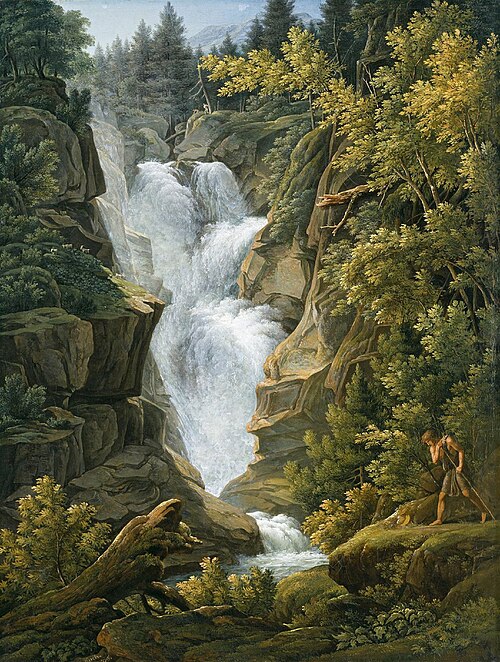

Joseph Anton Koch’s Waterfall in the Bern Highlands, painted in 1796, stands as one of the most powerful examples of early Romantic landscape painting. In this extraordinary work, Koch captures not just the majesty of nature, but its spiritual and emotional resonance—a hallmark of the Romantic movement that was just emerging at the close of the 18th century. This painting reflects Koch’s deep respect for the natural world, blending precise observation with poetic intensity, and invites viewers into a dramatic, almost sacred encounter with the Alpine wilderness.

In this analysis, we will explore the painting’s historical context, composition, symbolism, emotional power, and Koch’s broader contribution to the art of landscape painting.

Historical Context: The Emergence of Romanticism

By the late 18th century, European art was undergoing a profound transformation. The dominant style of Neoclassicism, with its emphasis on order, rationality, and classical ideals, was increasingly challenged by the emerging movement of Romanticism. Where Neoclassicism looked to the calm beauty of antiquity, Romanticism turned to the wild, untamed forces of nature, to emotion, the sublime, and the individual’s experience of the world’s grandeur.

Joseph Anton Koch (1768–1839), born in the Tyrolean Alps of Austria, was uniquely positioned to embody this transition. His early life amidst mountainous landscapes profoundly shaped his artistic vision. Although he spent much of his career in Rome, where he engaged with classical traditions, Koch’s most powerful works reflect the awe-inspiring drama of his native mountains.

In Waterfall in the Bern Highlands, painted when Koch was only in his late twenties, we see one of his earliest full expressions of Romantic landscape. The Bernese Oberland in Switzerland, with its towering peaks and plunging waterfalls, offered the perfect setting for his exploration of nature’s sublime power.

Composition: A Theatrical Encounter with Nature

The structure of Waterfall in the Bern Highlands immediately conveys a sense of grandeur. The composition is vertical, emphasizing the downward force of the cascading water and the towering cliffs that frame it. The waterfall dominates the center, cutting through a densely wooded, rocky gorge that leads the eye from the high mountain peaks down through the forested slopes to the calmer waters at the bottom of the painting.

The scene is enclosed by massive rock formations, which rise steeply on either side. Their rough, angular forms contrast with the fluid motion of the falling water, heightening the drama. Vegetation clings to the cliffs, with trees bending and twisting in response to the rugged terrain and the powerful spray from the waterfall.

Koch’s mastery of perspective and spatial arrangement creates a compelling depth. The eye is drawn both upward toward the mist-shrouded mountain peaks and downward along the waterfall’s path, creating a continuous movement that mimics the dynamic flow of water itself.

In the lower right corner, a lone figure stands, dwarfed by the surrounding wilderness. The tiny human presence serves to accentuate the monumental scale of the landscape and reminds the viewer of humanity’s relative insignificance in the face of nature’s immensity—a key theme in Romantic art.

Light and Atmosphere: A Study in Sublime Illumination

Light plays a critical role in establishing the emotional tone of the painting. Koch bathes the scene in a soft, almost ethereal light that filters through the forest canopy and highlights the spray of the waterfall. This illumination creates a sense of freshness and purity, enhancing the spiritual quality of the scene.

The light dances off the cascading water, rendering it simultaneously powerful and delicate. The fine mist rising from the base of the waterfall catches the sunlight, producing a luminous veil that adds depth and atmosphere.

Unlike the harsh, directed light of earlier Baroque landscapes, Koch’s lighting is diffuse, suggesting a natural, ever-shifting interaction between sunlight, moisture, and foliage. This approach allows the viewer to feel as though they are standing within the scene itself, experiencing the shifting light and cool dampness of the Alpine air.

The balance of light and shadow also serves to emphasize the contrasts between stability and movement, rock and water, permanence and transience—central tensions that give the painting its Romantic power.

Symbolism: Nature as the Sublime

Waterfall in the Bern Highlands is not a mere topographical study but a profound meditation on the sublime—a concept that was central to Romantic philosophy. The sublime refers to experiences that inspire both awe and terror, placing the viewer in a position of humility before forces greater than themselves.

In Koch’s painting, the waterfall symbolizes nature’s unstoppable power. Its ceaseless motion contrasts with the immovable cliffs and ancient trees, evoking a timeless cycle of change and permanence. The rocks suggest the enduring strength of the earth, while the rushing water reminds us of nature’s constant transformation.

The lone figure in the foreground, likely a traveler or shepherd, gazes toward the waterfall. This human presence serves as a surrogate for the viewer, inviting us to contemplate the scene not simply as an external spectacle but as an emotional experience. We share the figure’s awe, recognizing both the beauty and danger inherent in such an overwhelming environment.

In this sense, Koch’s work transcends mere landscape painting to become a spiritual reflection on humanity’s place within the vast, often incomprehensible forces of the natural world.

The Romantic Landscape Tradition

Koch’s Waterfall in the Bern Highlands sits at the intersection of several important artistic traditions. On one hand, it draws from the legacy of 17th-century landscape painters like Claude Lorrain and Jacob van Ruisdael, who celebrated nature’s grandeur and harmony. Yet Koch infuses this tradition with a new intensity and emotional charge, reflecting the Romantic desire to capture the sublime.

Unlike Neoclassical landscapes that often used nature as a backdrop for mythological or historical narratives, Romantic landscapes placed nature itself at the center. The wilderness is no longer merely decorative but becomes a subject worthy of reverence and deep contemplation.

Koch’s attention to naturalistic detail—every rock, tree, and stream carefully rendered—demonstrates his scientific curiosity and his close observation of nature. Yet he arranges these details into a composition that transcends mere documentation, creating an idealized vision of the Alpine sublime.

This blending of realism and idealization would influence later Romantic painters, including Caspar David Friedrich, who shared Koch’s fascination with humanity’s confrontation with nature’s immensity.

Emotional and Psychological Impact

Perhaps the most enduring power of Waterfall in the Bern Highlands lies in its emotional effect on the viewer. The painting evokes feelings of awe, wonder, and even a touch of fear—emotions that define the Romantic experience of the sublime.

The viewer is drawn into a world that feels both inviting and intimidating. The freshness of the foliage, the clarity of the rushing water, and the peaceful blue-gray mountains in the distance suggest nature’s serene beauty. Yet the towering cliffs, the force of the waterfall, and the small, vulnerable figure emphasize nature’s overwhelming scale and power.

This duality invites introspection. We are reminded not only of nature’s grandeur but of our own mortality and smallness within the cosmic order. The painting thus functions both as a celebration of nature’s beauty and as a spiritual meditation on human existence.

Technique and Artistic Mastery

Koch’s technique in Waterfall in the Bern Highlands reflects his exceptional skill as a draftsman and painter. Every element is rendered with clarity and precision, yet without sacrificing the overall unity of the scene.

The textures of the rocks are carefully articulated, with cracks, shadows, and surface variations that suggest ancient geological forces at work. The foliage is painted with remarkable attention to the diversity of leaf shapes, sizes, and colors, capturing the richness of Alpine plant life. The water, most challenging of all, is rendered with a delicate balance of transparency and motion, conveying both its weight and its ethereal spray.

Koch’s ability to combine such meticulous detail with a cohesive, emotionally charged composition demonstrates his mastery of the landscape genre. His work bridges the scientific observation of nature with the poetic aspirations of Romanticism, creating a vision that feels both true to life and elevated beyond it.

Koch’s Legacy in Art History

Although Joseph Anton Koch is sometimes overshadowed by more famous Romantic painters like Caspar David Friedrich, his contribution to the development of Romantic landscape painting is substantial.

Koch’s Alpine scenes brought a new seriousness to landscape art, elevating it to a vehicle for philosophical and spiritual inquiry. His influence extended to both German and Italian landscape traditions, inspiring artists who sought to capture nature’s grandeur not merely for aesthetic pleasure but as a means of contemplating humanity’s relationship with the natural world.

Koch’s blending of precise natural observation with emotional resonance helped lay the groundwork for 19th-century landscape movements across Europe, from the German Romantic tradition to the American Hudson River School.

Conclusion: Nature’s Eternal Voice

Waterfall in the Bern Highlands stands as one of Joseph Anton Koch’s greatest achievements, embodying the core ideals of Romantic landscape painting. In its towering cliffs, cascading water, and enveloping forest, we find a visual symphony of nature’s grandeur and mystery.

The painting invites viewers into a moment of profound contemplation—a space where beauty, power, and humility coexist. Koch transforms a specific Alpine scene into a timeless meditation on the sublime, offering not just a view of nature but an emotional encounter with its eternal forces.

More than two centuries later, Waterfall in the Bern Highlands continues to resonate with modern audiences who, in an increasingly industrialized and disconnected world, may find in Koch’s vision a reminder of nature’s enduring power to inspire awe, reverence, and reflection.