Image source: commons.wikimedia.org

Few portraits in the history of modern art embody the tension between classical tradition and modern abstraction as compellingly as Paul Cézanne’s unfinished masterpiece Gustave Geffroy, painted around 1895–1896. While Cézanne is most often celebrated for his revolutionary still lifes, landscapes, and bathers, his rare forays into portraiture reveal his intellectual and artistic struggles more nakedly. In Gustave Geffroy, we encounter not only a likeness of a man but a portrait of Cézanne’s search for order, structure, and emotional restraint within the modern world.

The subject of the painting, Gustave Geffroy (1855–1926), was an important French art critic, historian, and early champion of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. A close associate of Monet, Rodin, and other leading figures of the time, Geffroy was one of the first serious critics to appreciate Cézanne’s radical contributions to painting. His sympathetic writings helped to introduce Cézanne’s work to a broader intellectual public at a time when the artist was still largely misunderstood and marginalized by the mainstream art world. In gratitude, Cézanne agreed to paint Geffroy’s portrait, though their artistic collaboration would prove fraught and ultimately incomplete.

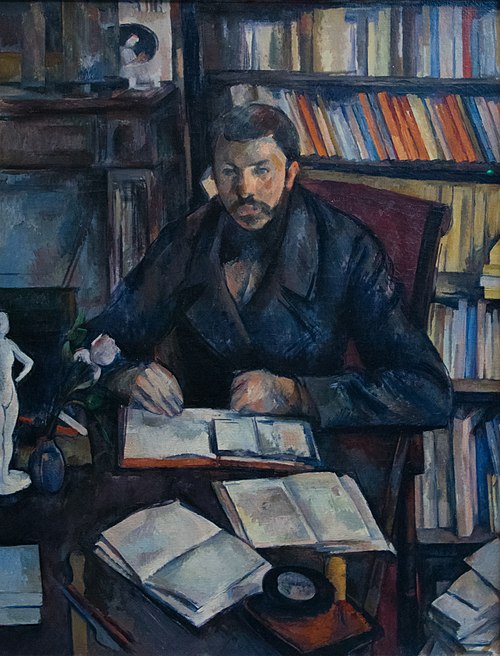

At first glance, Gustave Geffroy appears to follow many conventions of the intellectual portrait. The sitter is positioned at a large writing desk, surrounded by books, papers, and the tools of scholarship. Behind him, towering shelves of books line the background, emphasizing Geffroy’s identity as a man of letters. To his left sits a small sculpture, perhaps a nod to his wider interest in art and aesthetics. The setting is intimate but formal, framing Geffroy within the intellectual world he inhabited.

Yet beyond this initial recognition, the painting reveals itself as anything but conventional. Cézanne’s composition is marked by its structural complexity and deliberate tension. The viewer’s eye is drawn along multiple axes: the diagonal tilt of the desk, the triangular arrangement of books and papers, the rhythmic progression of vertical lines from bookshelves and chair, and the interlocking geometric planes that define every form. Even Geffroy’s seated body becomes part of this larger architectural structure, his broad shoulders and bent arms forming a pyramid that anchors the scene.

Cézanne’s treatment of space here is both ambitious and disorienting. Unlike the linear perspective of classical portraiture, where spatial depth recedes logically into the background, Cézanne’s space is fractured into a mosaic of overlapping planes and subtle shifts in perspective. The table seems to tilt slightly forward; the background bookshelves press uncomfortably close; the books on the desk appear both stacked and flattened. This spatial ambiguity is characteristic of Cézanne’s mature work and would exert profound influence on later Cubist painters such as Picasso and Braque.

The handling of Geffroy himself is equally complex. His head, set against a darker background, emerges with sculptural solidity. The features are modeled with Cézanne’s characteristic brushstrokes—short, chiseled planes of color that suggest volume without sacrificing surface texture. Geffroy’s expression is serious, focused, and slightly remote. His dark beard and hair blend into the muted tones of his clothing, allowing the face to emerge as the central focal point. Yet unlike the psychological intensity of a Rembrandt or Van Gogh portrait, Cézanne keeps emotional distance. The viewer is invited not into Geffroy’s mind, but into Cézanne’s analytical observation of form, volume, and relation.

Color in Gustave Geffroy is masterfully restrained. Cézanne employs a palette dominated by cool blues, earthy browns, and muted ochres, punctuated by the occasional warmer highlight—a pink flower in a vase, the orange-red bindings of books, the yellowed pages scattered across the desk. These controlled chromatic contrasts serve not to create visual drama but to stabilize the overall harmony of the painting. The restrained palette allows the structural relationships between forms to take precedence over coloristic effects.

The unfinished quality of the painting adds yet another layer of fascination. While the upper half of the composition is nearly complete, the lower half—particularly the books and papers on the desk—remains loosely sketched, with areas of exposed canvas and suggestive outlines. This incompletion may not have been entirely unintended; Cézanne struggled with the portrait for many months before abandoning it, reportedly dissatisfied with his ability to reconcile his formal ambitions with the demands of portraiture. The result is a kind of suspended resolution, where the viewer becomes acutely aware of the painting as a process of construction rather than a finished image.

Historically, the Gustave Geffroy portrait occupies a pivotal place within Cézanne’s development as an artist. By the mid-1890s, Cézanne had fully matured into the painter who would reshape the course of modern art. He had moved beyond the Impressionist concern with fleeting light and atmosphere toward a deeper investigation of structure, form, and permanence. His oft-quoted goal was to “make of Impressionism something solid and durable, like the art of the museums.” In this sense, Gustave Geffroy reflects Cézanne’s struggle to adapt this ambition to the genre of portraiture, where the depiction of personality and likeness traditionally stood in tension with formal abstraction.

Cézanne’s approach to portraiture was always uneasy. While he completed numerous portraits throughout his career—including many of his wife Hortense, his son Paul, and himself—he often approached these works less as psychological studies than as exercises in form. His sitters are frequently characterized by a kind of still, monumental detachment, their individuality subsumed into broader concerns with volume, balance, and compositional tension. In Gustave Geffroy, this tendency reaches one of its most extreme expressions. The portrait is not about Geffroy’s inner life but about the architecture of his physical presence within space.

Yet it would be a mistake to see Gustave Geffroy as cold or devoid of emotion. Beneath Cézanne’s formal rigor lies a deep, if restrained, respect for his subject. Geffroy was not only a champion of Cézanne’s art but a rare intellectual who grasped the significance of Cézanne’s revolution in seeing. In portraying Geffroy surrounded by books, art, and the labor of thought, Cézanne acknowledges their shared devotion to inquiry and intellectual labor. The portrait thus becomes a tribute to the kind of serious, disciplined attention that both men brought to their respective crafts.

One might also read Gustave Geffroy as a meditation on the artist’s own position within modern art. By the time of this painting, Cézanne was increasingly recognized as a pioneer of modern painting, though he remained isolated from the Parisian art establishment. His friendship with Geffroy represented a rare connection to the intellectual currents of the time. Yet in the painting’s unresolved spatial tensions, its hovering between completion and abandonment, we sense Cézanne’s own anxieties about the adequacy of his vision—his struggle to impose order on the complexity of perception.

From an art historical perspective, Gustave Geffroy stands as a harbinger of 20th-century modernism. The painting’s fractured space, planar organization, and abstraction of form anticipate many of the innovations that would define Cubism, abstraction, and even later conceptual approaches to portraiture. Picasso and Braque both acknowledged Cézanne’s influence as foundational to their breaking apart of form and perspective, and paintings such as Gustave Geffroy illustrate precisely the kind of analysis that would fuel these radical departures.

Beyond its formal innovations, however, the portrait resonates with enduring questions about the nature of representation itself. How does one capture not just the surface of a person, but their place within a larger structure of meaning? How does the artist balance observation with interpretation, fidelity with invention? In Gustave Geffroy, Cézanne confronts these questions directly, allowing the viewer to witness both his remarkable mastery and his persistent struggle.

Today, Gustave Geffroy remains one of the most fascinating and instructive works within Cézanne’s oeuvre. Its incomplete state invites us into the very heart of Cézanne’s creative process, exposing the painter’s labor in real time. Its fusion of traditional portrait conventions with radical spatial experimentation marks it as both a culmination of 19th-century realist traditions and a launching point for 20th-century modernism. In this singular image, we see Cézanne grappling with the very problems of art that would define modern painting for decades to come.

In conclusion, Gustave Geffroy by Paul Cézanne is far more than a simple likeness of an art critic. It is a masterclass in the tensions that defined Cézanne’s career: between classical order and modern abstraction, between observation and construction, between portraiture and structural analysis. Through its complex spatial architecture, restrained color palette, and suspended state of completion, the painting becomes a profound meditation on the nature of perception, the labor of seeing, and the very foundations of modern art. It stands as a testament to Cézanne’s role not only as a painter of extraordinary vision but as one of the essential architects of modern artistic thought.