Image source: commons.wikimedia.org

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Dante and Beatrice Meeting in Purgatory, painted in 1853, stands as one of the most emotionally charged and symbolically rich works of the early Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Deeply rooted in personal devotion, medieval romanticism, and spiritual allegory, the painting not only reflects Rossetti’s lifelong fascination with his namesake, Dante Alighieri, but also encapsulates many of the intellectual, aesthetic, and emotional concerns that defined his art and the wider Pre-Raphaelite movement.

Rossetti and the Cult of Dante

To fully appreciate Dante and Beatrice Meeting in Purgatory, one must first understand the central role that Dante Alighieri played in Rossetti’s artistic and personal life. Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882), born to an Italian émigré family in London, was named after the great Florentine poet. From his earliest years, Rossetti immersed himself in the study of The Divine Comedy and La Vita Nuova, which together formed the backbone of his romantic idealism and spiritual symbolism. Beatrice Portinari, Dante Alighieri’s muse and spiritual guide, became for Rossetti both a literary obsession and an archetype of unattainable, pure love.

This painting illustrates a moment drawn from The Divine Comedy, specifically from Purgatorio. In Dante’s narrative, after his journey through Hell, he encounters Beatrice in Purgatory. She appears not simply as the woman he once loved in life, but as a symbol of divine grace, leading him toward spiritual salvation. This reunion is both deeply personal and profoundly allegorical—a moment where earthly love transforms into a vehicle for eternal redemption.

Composition and Arrangement

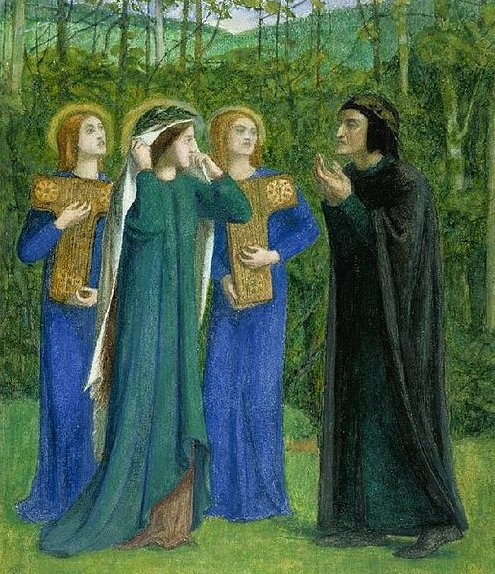

Rossetti’s composition is intimate and carefully structured. In a forested glade, Beatrice stands slightly apart, her head turned delicately as she acknowledges Dante’s presence. She is accompanied by two angelic attendants, both dressed in radiant blue robes and holding golden books — likely referencing the recording of human deeds and divine judgment. Dante, robed in dark garments, approaches her with an expression of reverence and longing, his hands raised in a gesture that suggests both supplication and awe.

The spatial arrangement is strikingly frontal, with the figures standing parallel to the picture plane. This compositional flatness, characteristic of early Pre-Raphaelite work, draws from the aesthetics of medieval Italian frescoes and manuscript illuminations. The visual simplicity creates an almost iconographic stillness, emphasizing the timeless, sacred nature of the encounter rather than a fleeting narrative moment.

Behind the figures, a wall of vertical tree trunks forms a natural backdrop, their rhythmic patterning contributing to the painting’s sense of order and quiet. The subdued, earthy greens of the forest set off the luminous figures in the foreground, allowing their colors and gestures to dominate the viewer’s focus.

Color and Symbolism

Color plays a central symbolic role in Dante and Beatrice Meeting in Purgatory. Beatrice’s gown is a rich emerald green, a hue often associated with hope, rebirth, and spiritual renewal. This aligns perfectly with her role in Purgatorio as Dante’s guide to ultimate redemption. Her veil and pale complexion create a soft luminosity, suggesting both her ethereal purity and her elevated spiritual status.

The two angels flanking her wear deep blue robes accented with golden embroidery, suggesting celestial wisdom and divine authority. The golden books they hold further reinforce the notion of eternal truth and divine law. The contrast between the angels’ vibrant blues and Beatrice’s green connects human love to the broader cosmic order, with Beatrice serving as an intermediary between earthly desire and heavenly justice.

Dante himself is robed in black, symbolizing both his penitential state and his still-unredeemed soul. His posture and gesture echo traditional depictions of pilgrims and penitent saints, emphasizing humility, yearning, and awe before the object of his devotion.

The entire color scheme reinforces Rossetti’s blending of emotional intimacy with spiritual transcendence. Each hue carries layered meanings, guiding the viewer’s understanding of the scene’s emotional and allegorical dimensions.

The Psychological Drama

Beyond its narrative source, Dante and Beatrice Meeting in Purgatory serves as a powerful exploration of the complex dynamics of idealized love. For Rossetti, this was not merely a literary subject but a deeply personal one. Throughout his life, Rossetti wrestled with his own experiences of unattainable love, loss, and mourning. The figure of Beatrice often stood in for his lost muse, Elizabeth Siddal, whose premature death haunted him for years.

In this painting, Beatrice’s reserved, almost aloof posture contrasts sharply with Dante’s intensity. She does not move toward him but acknowledges his approach with a kind of dignified detachment. This distance highlights the tension between earthly longing and spiritual fulfillment that defines much of Rossetti’s work. Dante’s visible yearning is not for physical reunion but for spiritual reconciliation—a love that transcends mortal limitations.

The psychological tension between presence and absence, between desire and sanctity, mirrors Rossetti’s own emotional struggles. His Pre-Raphaelite fascination with unattainable beauty, tragic muses, and divine femininity finds poignant expression in this carefully composed encounter.

Pre-Raphaelite Ideals in Full Expression

Dante and Beatrice Meeting in Purgatory is a quintessential Pre-Raphaelite painting in its technique and ideals. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848 by Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, and John Everett Millais, sought to reform British art by rejecting the academic conventions of the Royal Academy and returning to the purity, detail, and moral seriousness of early Renaissance art.

Rossetti’s use of bright, jewel-like colors, painstaking attention to detail, and flat compositional space reflects these early Renaissance influences, especially the work of Giotto, Fra Angelico, and Botticelli. The painting’s carefully drawn drapery, stylized halos, and decorative simplicity recall medieval illuminated manuscripts and church frescoes, which the Pre-Raphaelites admired for their sincerity and spiritual depth.

Moreover, the Pre-Raphaelite emphasis on literary themes, particularly those drawn from Dante and medieval romance, is fully embodied in this work. Rossetti saw himself not only as a painter but as a poet and translator, blurring the lines between visual and literary arts. His 1861 translation of La Vita Nuova demonstrates his lifelong immersion in Dantean literature, making his visual representations of these narratives deeply personal interpretations rather than mere illustrations.

The Broader Cultural Context

Rossetti’s painting must also be seen within the larger Victorian context, where the revival of medievalism served as both a reaction against industrialization and a means of exploring complex moral and emotional issues. The 19th century’s fascination with chivalric love, purity, and moral virtue provided fertile ground for Rossetti’s Dantean themes.

Yet Rossetti complicates this idealism by introducing psychological ambiguity. His Beatrice is not simply a radiant beacon of divine grace; she is also emotionally distant, even melancholic. The subtle tensions in their interaction reflect not only theological concerns but also Victorian anxieties about gender, purity, and unattainable ideals.

Victorian viewers would have recognized in Dante and Beatrice Meeting in Purgatory both the elevation of pure love and its inherent sadness. The separation between Dante and Beatrice mirrors the broader Victorian tendency to elevate women as angelic figures while simultaneously denying them full emotional or spiritual autonomy—a dynamic that Rossetti both participates in and critiques through his art.

Rossetti’s Personal Mythology

Throughout his life, Rossetti cultivated a highly personal mythology around the figures of Dante and Beatrice. This painting is not merely an illustration of Purgatorio but an expression of Rossetti’s ongoing dialogue with his own creative identity. Like Dante, he saw himself as both a poet and artist whose life was shaped by the loss of an idealized love.

The parallels between Beatrice and Elizabeth Siddal are difficult to ignore. Siddal, Rossetti’s muse, model, and wife, died in 1862 after years of illness and depression. Rossetti’s grief was profound and haunted much of his later work. In Beatrice, he found a mythological mirror for his own mourning—a woman elevated to spiritual perfection after earthly loss.

By painting Beatrice as both accessible and untouchable, Rossetti confronts his complex feelings of longing, loss, and transcendence. The painting becomes a deeply personal meditation on love’s ability to endure beyond death, yet remain forever unattainable.

Influence and Legacy

Dante and Beatrice Meeting in Purgatory exemplifies many of the innovations that would come to define Rossetti’s influence on Symbolism and Aestheticism later in the century. His emphasis on mood, atmosphere, and symbolic meaning over strict narrative realism helped pave the way for the poetic visual languages of artists like Edward Burne-Jones, Gustave Moreau, and even the early works of Gustav Klimt.

Rossetti’s fusion of poetry and painting also helped legitimize the idea of the artist as a multi-disciplinary visionary, blurring the boundaries between art forms. His work foreshadows many of the modernist explorations of inner states, archetypal figures, and ambiguous narratives that would dominate the 20th century.

Even today, Dante and Beatrice Meeting in Purgatory remains a touchstone for understanding not only Rossetti’s personal artistic journey but the entire ethos of the Pre-Raphaelite movement—a world where beauty, spirituality, literature, and personal emotion were inseparably entwined.

Conclusion

In Dante and Beatrice Meeting in Purgatory, Dante Gabriel Rossetti offers more than a simple scene from The Divine Comedy. He presents a deeply layered meditation on love, loss, salvation, and idealization. Through his careful composition, jewel-toned palette, and psychologically charged figures, Rossetti transforms a literary encounter into a timeless visual poem. The painting stands not only as a masterwork of Pre-Raphaelite art but as a personal shrine to the artist’s lifelong preoccupations with devotion, mortality, and the spiritual dimensions of beauty.

Rossetti’s Beatrice, poised delicately between grace and distance, continues to captivate viewers with her serene beauty and unresolved emotional complexity. In this suspended moment of reunion, Rossetti captures the eternal longing at the heart of both Dante’s poem and his own artistic vision—where the boundaries between mortal love and divine salvation are forever intertwined.