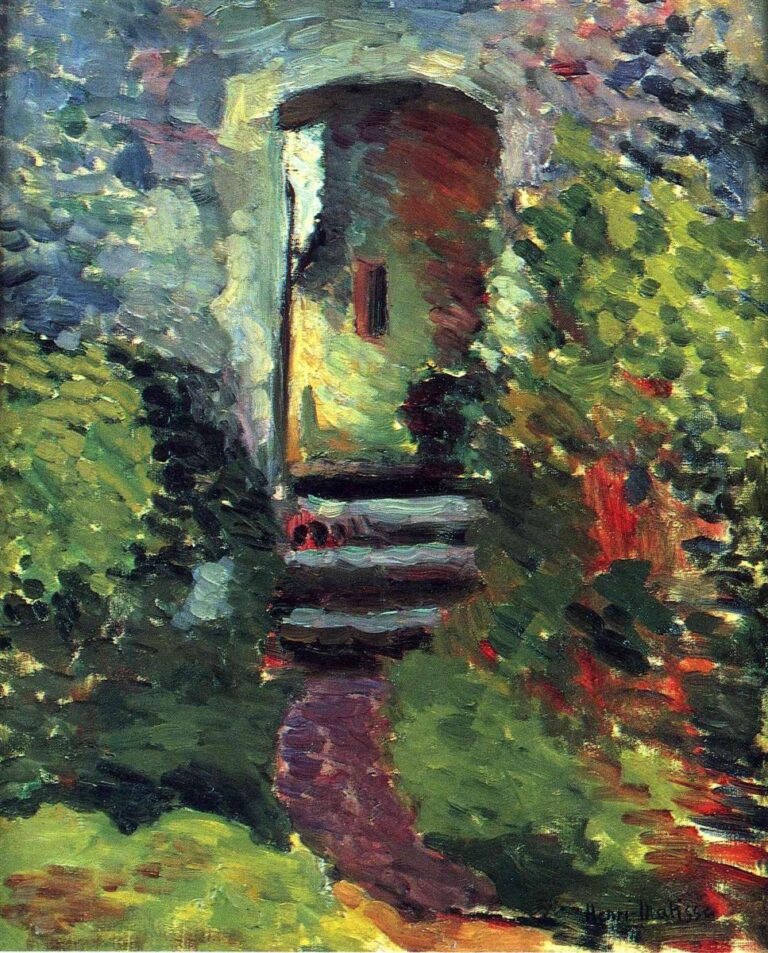

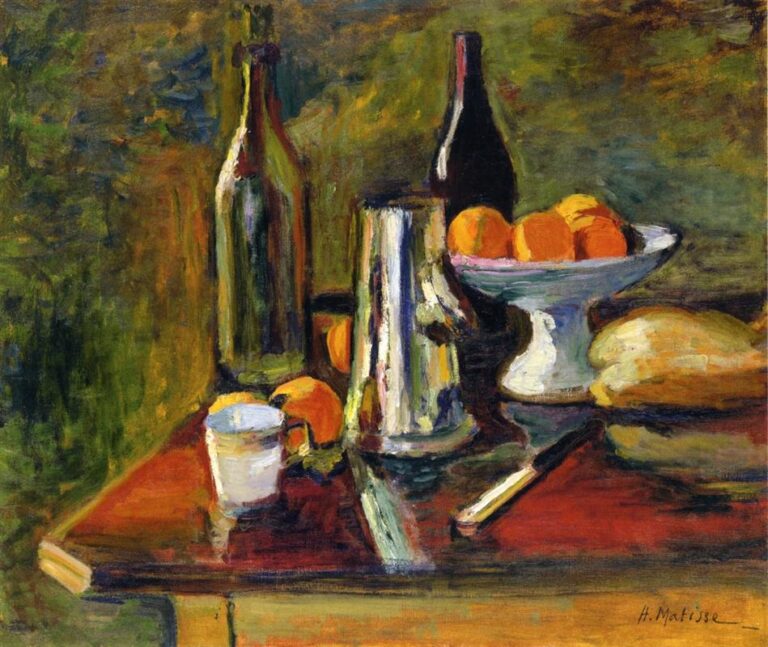

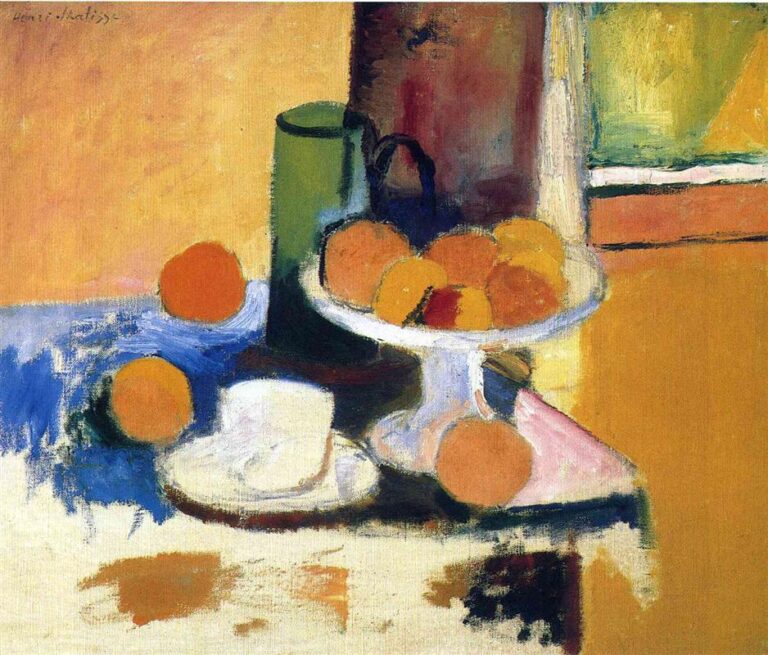

A Complete Analysis of “Still Life with Oranges II” by Henri Matisse

Painted in 1899, “Still Life with Oranges II” condenses a tabletop of commonplace objects into a daring architecture of color. A cool green jug, a white compote heaped with oranges, and a small cup surge forward against planes of saffron, peach, and ultramarine. Edges are built by temperature rather than line, and large unblended passages test how far color alone can describe light, space, and touch. This compact canvas records Matisse’s decisive turn from tonal realism toward the liberated language that will soon crystallize as Fauvism.