Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

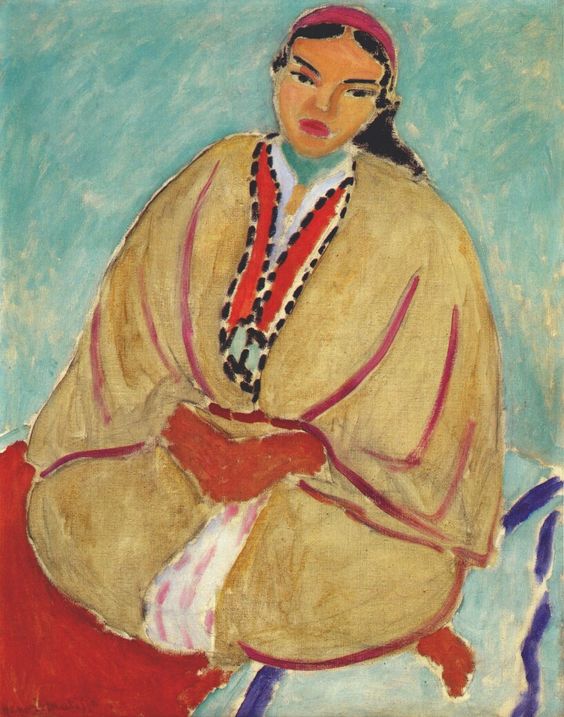

Henri Matisse’s “Zorah in Yellow” (1912) belongs to the luminous cluster of paintings the artist made during his first stay in Morocco. It is both a portrait and an experiment in building an image through fields of color, compressed drawing, and a few carefully tuned accents. Seated close to the picture plane, Zorah fills the canvas with the quiet mass of her yellow burnous. The surrounding air is an even, windless turquoise. A braid-like chain of dark and red strokes travels down her chest; a ribbon of rose outlines the garment’s arcs and seams; a flare of red at the lower edge anchors the figure to the ground. Nothing in the painting feels stagey or theatrical; it is poised and direct, as if the artist set out to honor the sitter’s presence by stripping the picture to essential intervals of hue, edge, and rhythm.

A First Look at the Image

Zorah sits cross-legged, her hands folded softly at her lap. The face is frontal but not rigid, turned just enough to break strict symmetry. The head is wrapped with a rose band or scarf that catches the same chromatic note used to articulate the burnous. The eyes are simplified ovals with dark lids; the mouth is a compact shape set low in the face, giving the expression a calm reserve. The garment’s yellow is not uniform; it drifts from sandy ochre to warm straw, occasionally allowing the tooth of the canvas to sparkle through. The background is a single atmosphere, a sea-glass blue brushed in broad, directional strokes that give the plain field a faint, breathing motion. The overall effect is of stillness held within color.

Format, Scale, and the Architecture of the Figure

The painting’s format—neither fully square nor strongly vertical—suits a seated figure that gathers into itself. Matisse uses the garment’s crescents to build a series of nested arcs that echo the canvas’s perimeter. The lower hem curves upward just inside the bottom edge; higher seams trace larger arcs that guide the viewer’s eye back toward the center; the topmost contour, resting at the shoulders, prepares the rise of the head. These arcs create a shell-like enclosure around Zorah’s face and hands, concentrating attention without forcing it. Within this architecture, small diagonals—folds at the elbow, the angle of the headband, the prismatic wedge of a white underscarf—keep the composition from becoming static. The format is not neutral framing; it is a chosen geometry that makes the body the room it inhabits.

Color as the Engine of Portraiture

Matisse constructs identity through color relationships rather than meticulous description. The yellow garment is the key signature; every other hue tunes itself around this central pitch. Because the ground is cool turquoise, the yellow reads warm rather than bright, like sunlight stored in cloth. The rose outline is not decorative trim: it is the complementary note that clarifies the yellow’s temperature and gently magnetizes the eye along the garment’s edges. A narrow ladder of black and red down the chest intensifies the center without turning fussy; it functions like a spine of accents around which the large fields can breathe. The face, modeled minimally, is a set of warm ochres and pinks that resonate with the burnous while standing apart from it. The few blues in the underscarf or beneath the knees do the same work as the ground, reinforcing the cool–warm dialogue that carries the whole painting.

Drawing with the Brush

Contour in “Zorah in Yellow” is painted, not drawn in pencil and colored afterward. You can feel the weight of the brush as it writes the garment’s arcs, thickening on a turn and thinning as the hand lifts. Inside forms, the brush marks are broad but clear. Matisse avoids the temptation to model folds with crosshatching or tight shading; he lets one stroke define direction, another set an edge, a third lay a flat region of color. This refusal of fuss keeps the figure monumental and lucid. Notice the small economy of marks that establish the face: a curved stroke for the brow, a brief flare for the nose, two dark commas for the eyes, a compact lip. The writing is spare but sensitively pitched; the face reads at once, yet holds nuance upon longer looking.

Light by Adjacency Rather than Illusion

There is no spotlight in this painting, no cast shadow anchoring the figure, no theatrical lighting. Instead, the sensation of light comes from adjacency. A lighter passage of yellow appears brighter because a rose outline hugs it; the turquoise ground feels luminous because it wraps a warmer form; the face glows where a cool note touches its edge. This strategy keeps the surface unified: every region participates in the same climate and breathes the same air. The result is neither flat nor illusionistic; it is pictorial light, built from relationships rather than tricks.

The Burnous as Structure and Symbol

The burnous, a capacious outer garment, gives Matisse the large planes he favors. Its size lets him reduce the body to a nearly abstract mass without losing dignity or presence. The garment’s outlines become the architecture of the picture; the folded hands are a small sanctuary at its center. Emphasizing this form resists the typical temptations of portraiture in unfamiliar cultures. There is no catalog of ethnographic detail, no performance of “otherness.” The garment is not costume; it is structure, allowing color and rhythm to stand in for narrative. Simultaneously, the burnous carries quiet cultural specificity through its shape and drape, signaling place and tradition without illustration.

The Psychological Temperature of the Pose

Zorah’s posture—cross-legged, shoulders relaxed, hands gathered—communicates composure without self-consciousness. The slight forward lean implies attention; the turned head softens the formality of the frontal pose; the folded hands organize the center. Matisse neither sentimentalizes nor dramatizes the sitter. He lets attitude arise from a few structural choices: the nested arcs of the garment, the downward ride of the eyes, the small counter-curve in the headband, the gentle asymmetry of the sleeves. The face is calm but not blank. Because the modeling is restrained, the viewer reads emotion through color and shape rather than facial theatrics. The psychological temperature is therefore steady and humane.

Background as Silent Atmosphere

The ground is a single, cool field of turquoise-blue broken by soft shifts of value and direction. Instead of telling us where Zorah sits, Matisse builds an atmosphere that sets off her form as a relief. The coolness of this space makes the warm garment advance; the softness of the brush marks keeps the field from turning decorative. A few slivers of rose and blue at the bottom edge hint at the surface on which she sits, but these are rhythm more than narrative. The background’s reticence gives the figure room to breathe and preserves the painting’s clarity.

Edge, Halo, and the Push-Pull of Planes

Matisse often uses small halos of ground or return strokes of garment color to adjust edges. Along the sleeves and hem you can see places where yellow slips over turquoise and is corrected by a thin return of cool paint, or where the rose line rides a fraction outside the yellow, creating a crisp seam. These micro-edges enact a push-pull that animates the surface. The body appears to press forward, the background to yield. The slight tremor of these edges keeps the painting alive at every scale; there is no dead, ruler-straight boundary to detach the figure from its air.

Material Surface and the Trace of Making

The painting records its own order of decisions. A thin wash of turquoise sets the ground; warm yellows are scrubbed over it, allowing occasional flecks of blue to sparkle through. The rose outline arrives as a later, faster pass, its speed evident in the tiny tails and thickenings where a curve tightens. The dark-and-red chain at the center sits on top of these layers like calligraphy. Small adjustments remain visible, especially at the hand and lower hem, where alternatives were tested and then partially painted out. This transparency of process contributes to the painting’s honesty. It is not an image polished into anonymity; it is a set of choices you can see and feel.

Relation to Matisse’s Moroccan Cycle

“Zorah in Yellow” speaks to the family of works Matisse made in Tangier, including portraits of Fatma and Zorah in different poses, and the tall standing figure of “The Moroccan Amido.” What unites them is the discipline of simplification, the reliance on saturations of cool and warm, and the refusal to turn setting and costume into spectacle. What distinguishes this canvas is its emphasis on the burnous’s nested architecture and the decision to stage the figure so close to the viewer that garment becomes landscape. Among the cycle, it may be the most quietly monumental: not the tallest, not the most dramatic, but the one in which a single color field—the yellow of the cloak—carries the most structural weight.

Decorative Intelligence Without Excess

Decoration in Matisse’s work is never added on; it is in the bones of the composition. Here, the only overtly decorative element is the central necklace or braided tie, painted as a ladder of black and red touches. Rather than multiply patterns, he restricts himself to this one linear figure, using it to stabilize the central axis and to inject a vigorous rhythm that counters the garment’s broad planes. The rose outline plays a similar role: it is a structural ornament that clarifies and binds rather than embroidering details. This discipline allows the painting to speak in a few strong syllables instead of many small ones.

Space Without Perspective

The canvas offers almost no orthodox spatial cues. There is no cast shadow, tiled floor, or receding wall. Depth is suggested by overlaps (hands over garment, garment over edge), by value steps (warmer yellows forward against cooler ground), and by the scale of the figure relative to the canvas. This compressed, shallow space is a deliberate modern choice. It keeps attention on the relationships that matter—color, contour, rhythm—rather than expending energy on the illusion of room. You feel the nearness of the sitter not because of tricks of perspective but because the painting has collapsed the distance between her and the viewer.

Cultural Specificity and the Ethics of Looking

Painted by a European artist in North Africa in 1912, the portrait invites scrutiny about representation. Matisse’s method is notable for its restraint. He does not stage an exotic scene; he does not turn clothing into costume drama; he avoids voyeurism by anchoring the sitter’s gaze and posture in calm self-possession. The painting transmits difference—of dress, of light, of setting—without turning the sitter into a curiosity. It exemplifies a way of looking across cultures that privileges attention over appropriation and clarity over spectacle.

Echoes, Anticipations, and Afterlife

Several features of “Zorah in Yellow” anticipate Matisse’s later achievements. The translation of a body into nested, near-abstract shapes foreshadows the cut-outs, where leaves, dancers, and figures are reduced to essential silhouettes. The reliance on a dominant field color animated by a few accents presages the organizing strategies of “The Red Studio” and “The Pink Studio.” Designers, photographers, and painters have all learned from this economy: that a single strong field tuned by sparing contrasts can carry complex emotion and presence.

Looking Slowly: What to Notice Over Time

A first glance at the painting gives you color and posture. A second and third reveal small calibrations that account for its staying power. The rose outline is not one color but several notes, sometimes hotter, sometimes cooler, sometimes thinning to near-nothing where the garment needs to soften. The face carries a faint asymmetry—the right eyebrow rides a shade higher; the mouth’s corners are not twins—that prevents the portrait from freezing. The hands, schematized and warm, echo the red wedge at the lower edge, as if warmth were pooling at the center. The turquoise ground, brushed in directional swaths, quietly sets a circular motion around the figure, keeping the stillness alive.

Why the Painting Still Feels New

The painting’s freshness lies in its clarity. Many portraits attempt to persuade with detail; “Zorah in Yellow” convinces with decisions. Every element—format, color, line, pose—serves a single purpose: to let a person’s presence occupy space without noise. Because the means are pared down, nothing dates. The yellow is not a fashion hue; it is a structural choice. The contour is not a mannerism; it is a functional edge. The atmosphere is not locale for its own sake; it is the necessary climate for these forms to exist. The painting’s modernity is not a style but a method.

Conclusion

“Zorah in Yellow” is a portrait of composure built from color’s simplest verbs: warm against cool, curve against plane, accent against field. The garment’s nested arcs make an architecture that shelters the face and hands; the turquoise ground holds the whole like air; spare contours write the body rather than tracing it; light is made by adjacency, not illusion. Matisse’s restraint does not flatten identity; it honors it. The picture meets the viewer with serenity, confident that a person can be fully present in a few tuned notes. In this confidence lies the work’s enduring radiance.