Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

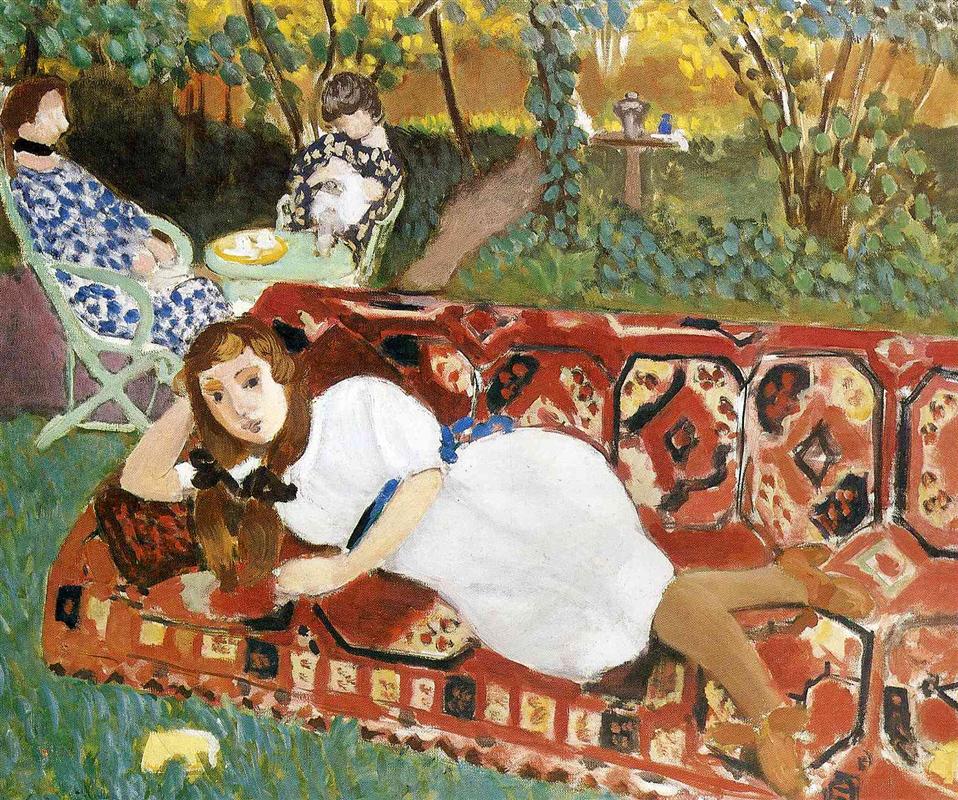

Henri Matisse’s “Young Women in the Garden” (1919) stages an afternoon of ease as a play of color, pattern, and posture. A girl in a white dress reclines across a scarlet Oriental carpet spread on the lawn, her long hair gathered with dark ribbons and her gaze turned outward. Behind her, two companions in blue patterned dresses sit at a small table beneath a canopy of leaves. The garden glows with late light; a stone pedestal at the right catches a spill of yellow, while ivy and shrubs weave a loose screen across the back of the scene. Nothing appears forced or theatrical, yet everything is designed. Matisse converts a casual moment into a modern orchestration where textiles act like architecture and color establishes space as surely as any perspective lines.

Historical Context

The painting belongs to Matisse’s early Nice period, a time when he turned from prewar turbulence to rooms, balconies, and gardens warmed by Mediterranean light. In 1919 he repeatedly explored domestic leisure—reading at a table, reclining on a couch, standing at a balustrade with a parasol—and he treated these scenarios not as anecdote but as opportunities to test the structural powers of color. “Young Women in the Garden” extends that project outdoors. It brings the signature elements of his interiors—patterned fabrics, shallow space, living contour—into a landscape, suggesting that his decorative logic is portable. The spread carpet becomes a movable room, a red island of design in the field of grass, and the garden itself behaves like a painted backdrop.

The Motif of Leisure

Three figures share the garden’s stage. The foreground model reclines, leaning on one arm with her body stretched diagonally across the carpet; this pose declares ownership of the red ground and gives the composition its major vector. Behind her, two companions sit at a small round table in wicker chairs. Their patterned blue garments echo one another, and their conversation or quiet companionship reads as a sustained chord rather than a narrative incident. Matisse favors the interval between actions, the pause in which people simply inhabit color, air, and texture. Leisure here is not decadence but the tempo that lets seeing take place.

Composition and Framing

Matisse builds the image on a strong diagonal created by the reclining figure and the carpet’s long edge. That diagonal is countered by the vertical trunks and clustered shrubs that fill the background. The scene divides into three horizontal bands: foreground carpet and lawn; middle band of seated women and table; background of trees and warm sky. The foreground figure anchors the design at the lower left, her head near the central seam and her feet toward the right edge; this skewed placement pulls the viewer into the scene without centering it, keeping the picture lively. Overlap is key: the white dress interrupts the carpet’s pattern; the carpet interrupts the lawn; the shrubs partially veil the upper table. These interlocks create depth without sacrificing the surface unity of color.

Color Architecture

Color does the architectural work. The red carpet is the dominant plane, a saturated ground that supports everything placed upon it. Its palette of scarlet, brick, and black delivers a warm bass line, and its repeating diamonds and medallions establish a steady beat. Against this warmth Matisse sets three cooling elements: the white of the recumbent figure’s dress, the light blue bows and shadows along her form, and the patterned blues of the seated companions. Fresh green grass adds a middle temperature, transitioning the eye from the carpet’s heat to the foliage’s cooler canopy. Small sparks—yellow on the pedestal, a pale plate at the table, flashes of skin—keep the harmony bright. Because each color family appears in more than one place, the eye experiences connection rather than contrast: the blues converse across the depth of the picture, the whites repeat in dress, plate, and specks of sunlight, and the reds echo faintly in the background earth.

Light and Atmosphere

The light is gentle, filtered through leaves rather than striking directly. It softens the white dress so it glows without glare, and it lets the carpet’s reds breathe. The upper garden shimmers with a warm, late-afternoon tone, more amber than gold, and that warmth binds the entire scene together. No cast shadow is allowed to dominate; modeling is achieved by temperature shifts and by the direction of the brush. This even climate is typical of the Nice period: light is an ally of harmony rather than a producer of drama.

Pattern as Structure

Pattern drives the composition. The carpet’s geometric tessellation provides the picture’s main grid, a portable architecture that keeps the surface coherent. The two blue dresses echo the idea of pattern at a smaller scale—a field of blossoms replacing the carpet’s diamonds—so that figure and ground belong to the same decorative family. Even the foliage participates: rounded leaves repeat like a green mosaic across the upper band, and the ivy on the right descends in a regular wave. Pattern here is not an overlay; it is the very skeleton of the painting, a system of repeats and variations that holds space and rhythm.

The Foreground Figure: Gesture and Presence

The reclining girl’s pose mixes ease and alertness. With her head propped on one hand and her other arm draped forward, she seems absorbed but not asleep; her gaze approaches the viewer directly, turning the foreground into a meeting place. The white dress, simplified into large planes, refuses the plush suggestiveness of satin modeling; it reads as light caught on cloth. Brown shoes, long hair tied with black ribbons, and a blue belt or bow add compact accents that keep the form grounded. The figure possesses the carpet without sinking into it; a narrow contour draws the line between body and pattern, maintaining the clarity that Matisse prizes.

The Seated Pair: Counterpoint and Depth

The two women at the table form a companion chord. Their dresses mirror one another in color but differ in posture: one leans back, the other forward as if occupied by a small object or pet. Between them, a pale plate sits on the tabletop like a quiet moon. They are set back just enough that the carpet can dominate without swallowing them, and their blue dresses project coolness into the warm middle distance. They give the painting the social counterpoint it would lack if it were only a single reclining figure; they are evidence of time continuing beyond the front stage.

The Garden as Stage

The rear band of shrubs and trees functions like a theatrical backdrop painted with leaves. Matisse compresses the space by allowing the foliage to meet the seated figures’ shoulders; at the right a trunk ascends into a burst of yellow-green. A stone pedestal with vessels and two small blue touches—perhaps birds or glass—stands as a still-life punctuation mark. This back wall of vegetation is not a depth illusion in the nineteenth-century sense; it is a screen that declares the painting’s surface even as it supplies the feeling of a place. The garden is not a realistic expanse but a zone of color in which human presence can unfold.

Rhythm and Movement

Though the scene describes rest, the design pulses with movement. The carpet’s medallions create a marching rhythm across the plane; the reclining body places a long slur over that beat; the row of shrubs breaks into syncopated clusters; and the tree trunk thrusts upward like a countermelody. Small curved accents—ribbons, shoes, the rounded tabletop—soften the angularity of the carpet and keep the overall song supple. The viewer’s eye naturally travels in a loop: it begins at the foreground face, passes along the red field to the right, rises through foliage and pedestal, crosses to the seated pair, and descends again to the carpet’s left edge. Each circuit confirms the painting’s compositional music.

Drawing and the Living Contour

Matisse’s contour is visible and humane. He sets the outline of the reclining figure with a supple, dark line that thickens and thins as it moves; it never cages the form, but it gives color something to press against. The seated women’s profiles are written in spare strokes that capture posture rather than detail. Leaf clusters are laid down with rounded touches that never calcify into neat ovals. The carpet’s pattern is plotted boldly, with occasional compressions or shifts that announce the hand rather than a mechanical repeat. This living line prevents the painting from sliding into mere decoration; it keeps breathing audible.

Material Presence and Brushwork

The paint varies in thickness according to the job at hand. The carpet’s reds are laid in with generous, slightly dry strokes that reveal the weave beneath and suggest nap. The white dress is thinner, almost scumbled, so it can catch surrounding hues and transmit light. The foliage is dabbed and pulled in small clusters, producing a mosaic of greens that reads as vibrating leaves rather than as botany. Across the surface Matisse leaves decisions legible—changes of mind are visible in a shifted contour or a repainted patch. That legibility gives the scene a present tense; we feel the making as well as the viewing.

Space: Shallow, Breathable, Modern

Depth is acknowledged but kept short. The overlapping of carpet, figures, and shrubs cues recession; the scaling of forms—large in front, smaller in back—confirms it. Yet perspective lines are absent, and the back band behaves like a decorative screen pressed near the surface. The result is a modern compromise in which painting remains an object while inviting habitation. We can imagine stepping onto the red carpet, yet we never forget that we are looking at color arranged on a plane.

The Carpet as Portable Interior

A central insight of the painting is the transformation of an interior device into an outdoor stage. The patterned carpet, familiar from Matisse’s couches and studio floors, is relocated to the grass. It carries with it all the structural benefits he enjoys indoors—flat pattern to unify the field, warm plane to support skin tones, a repeat to measure the eye’s progress—yet it meets open air and natural light. By laying an interior across the lawn, Matisse dissolves the boundary between domestic calm and landscape freedom. The garden becomes another room; the room becomes another patch of garden.

Dialogue with Tradition

“Young Women in the Garden” converses with a century of images of leisure—Renoir’s garden parties, Manet’s picnics—while updating their language. The figures’ dresses and the casual table nod to that lineage, but Matisse refuses anecdote and atmospheric shimmer. He keeps the surface organized by large colored shapes, lets pattern carry the burden of description, and compresses depth to preserve clarity. In doing so he proves that a modern decorative logic can host the same pleasures Impressionists once pursued—companionship outdoors, warmth, dappled air—without imitating their techniques.

Psychology without Drama

There is no explicit narrative, yet the trio’s arrangement suggests a psychology of gentle independence. The reclining figure addresses us directly; the seated pair converse among themselves. Each person occupies a distinct patch of pattern and light, and their separateness breeds harmony rather than tension. Matisse refuses melodrama; he proposes that order itself—clear relations of color, scale, and distance—can produce an atmosphere of well-being that registers as feeling.

How to Look

A rewarding way to approach the painting is to accept its decorative structure as guide. Begin at the foreground face and feel the firmness of its contour. Let your gaze travel along the red carpet’s edge, noting how the pattern compresses near the corners and opens where the body interrupts it. Step up the diagonal trunk toward the stone pedestal, then drift to the seated pair and the pale plate at their table. Cross the line of shrubs and descend through the grass’s cooler greens back to the carpet. Each loop reveals small harmonies—the echo between blue dresses and blue bows, the way brown shoes answer the carpet’s darker medallions, the dialogue between white dress and white glints on distant objects.

Lasting Significance

“Young Women in the Garden” encapsulates the Nice period’s conviction that harmony can be rebuilt from everyday things: a blanket spread on grass, a conversation at a small table, light falling through leaves. By importing the architecture of pattern into the outdoor world, Matisse declares that painting’s order is not confined to rooms. The work anticipates the late cut-outs in which leaf and fabric become pure silhouette, even as it celebrates oil’s softness and the nuanced climates of daylight. It remains a generous image, hospitable to the eye, confident that the decorative—rightly understood—can support human presence with dignity.

Conclusion

Matisse’s garden scene is less a transcript of an afternoon than a proposal for how to see one: through tuned color, breathing contour, and pattern that doubles as structure. The red carpet plants a portable interior on the lawn; the reclining girl gives it axis and scale; the seated companions supply balance and depth; the foliage frames a shallow, luminous stage. Each element participates in a system of repeats and variations that keeps the surface alive while granting the figures calm. In 1919, after years of upheaval, such lucidity amounted to solace. Today it still offers the same invitation: to move through the world at the pace of looking and to find order in simple, generous relationships of hue and shape.