Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

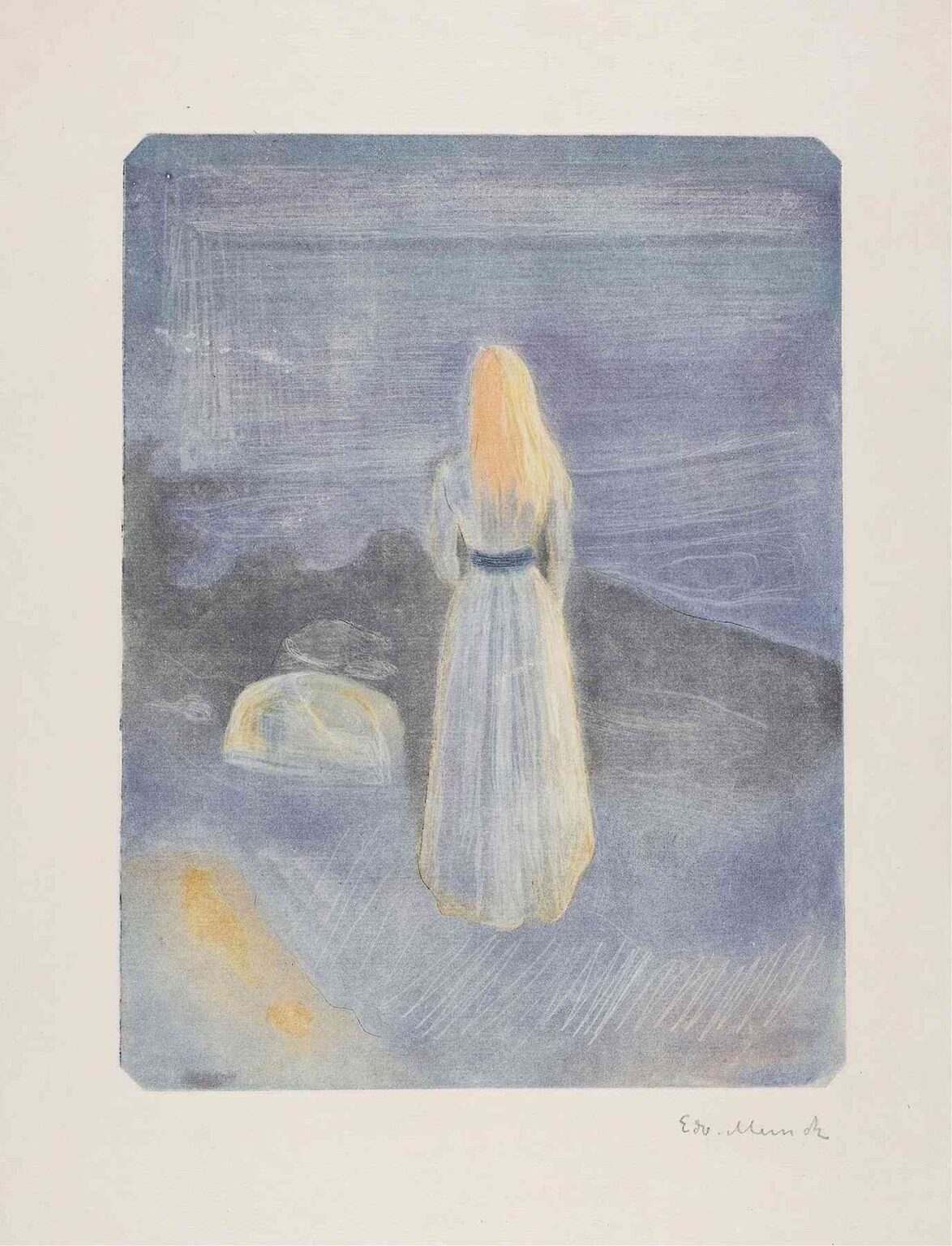

Young Woman on the Beach (1896) by Edvard Munch is a haunting woodcut that captures a solitary female figure standing at the water’s edge, her back turned to the viewer as she gazes out across a vast, shadowy seascape. Executed at a pivotal moment in Munch’s career, this print exemplifies his mastery of relief techniques and his enduring fascination with the intersections of memory, emotion, and landscape. Through its spare composition, nuanced tonality, and evocative symbolism, Young Woman on the Beach transforms a simple seaside scene into a profound meditation on solitude, yearning, and the liminal space between land and sea, conscious and unconscious.

Historical and Biographical Context

By 1896, Edvard Munch (1863–1944) had established himself as a leading figure in the Symbolist movement. Following his early training at the Royal School of Art and Design in Kristiania (now Oslo) and formative travels in Paris and Berlin, Munch returned to Norway brimming with new ideas about art’s capacity to express inner states. Personal tragedies—the death of his mother in 1868 and his sister Sophie in 1877—intensified his interest in themes of grief, anxiety, and existential reflection. In the mid-1890s, he began to explore woodcut printmaking as a means to broaden the dissemination of his images, experimenting with color and registration to capture fleeting moods. Young Woman on the Beach emerges from this period of technical innovation and psychological exploration, reflecting Munch’s ambition to externalize subjective experience through bold, graphic means.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Munch arranges Young Woman on the Beach in a vertical format, dividing the image into discreet spatial registers. The lower third is occupied by the pale, rippling shoreline and the woman’s flowing gown. Above, a dark, horizontal band of land or rock serves as a visual barrier, anchoring the figure and separating her from the open sea. The upper half of the composition is dominated by the sea and sky rendered in soft, bluish washes. The woman stands slightly off-center, her slender form interrupting the horizon line. This placement heightens her vulnerability and underscores her isolation. The receding lines of her dress and the undulating water surface guide the viewer’s eye outward, creating a dynamic tension between her interior focus and the boundless expanse before her. Negative space abounds around and beyond her, inviting contemplation of what lies both within and beyond the frame.

Color Palette, Light, and Atmosphere

Although executed as a woodcut, Young Woman on the Beach employs subtle color modulation—soft blues, pale yellows, and muted grays—achieved through delicate inking and hand-applied washes. The pale tones of the woman’s dress and hair suggest luminescence, as though she is bathed in moonlight or early dawn’s first glow. In contrast, the band of land behind her is rendered in deep indigo, providing a stark counterpoint that intensifies the sense of separation from the watery horizon. The sky and sea display barely perceptible gradations, moving from deeper hues at the top to lighter washes near the shore. This atmospheric subtlety evokes a time of day when light is transitory—twilight or pre-dawn—symbols in Munch’s work of both endings and new beginnings. The overall effect is one of stillness tinged with anticipation: the world holds its breath, and the viewer shares in the woman’s quiet waiting.

Technique and Printmaking Innovations

Munch’s approach to color woodcut was unconventional and experimental. For Young Woman on the Beach, he carved multiple blocks, each corresponding to a different hue, and meticulously registered them to align the final image. Unlike the clean precision favored in traditional Japanese prints, Munch allowed the wood grain to show through in areas of light inking, its vertical striations imparting a tactile quality to the water and sky. He varied the wiping of the block to achieve painterly gradations, letting the paper’s natural tone contribute to the composition. Hand-applied color—particularly in the figure’s gown and hair—adds a personal touch, as no two impressions are exactly alike. These technical choices reflect Munch’s belief that printmaking should be an extension of painting, capable of capturing nuance and emotional depth rather than merely reproducing line work.

Symbolism and Thematic Interpretation

The solitary figure at the water’s edge has long served as a symbol of introspection and existential longing in art. In Young Woman on the Beach, the woman’s back turned to the viewer creates both distance and invitation: we witness her contemplation, yet remain strangers to her interior world. Water often signifies the unconscious, memory, and emotional depths; the barely delineated horizon suggests the edge of consciousness, a boundary both terrifying and magnetic. The land barrier behind her can be read as the safety of the known world—or the obstacles that keep her from fully immersing herself in the depths. Munch’s signature symbolist motifs—thresholds, shorelines, twilight—here converge to evoke the tension between yearning and retreat, the pull of the unknown and the comfort of what lies behind.

Psychological Dimensions

Munch’s art is deeply rooted in the exploration of mental and emotional states. Young Woman on the Beach captures a moment of poised stillness, where the figure’s posture—straight-backed yet relaxed—suggests readiness as much as resignation. Her position at the edge of two realms embodies the psychological dynamic of transition: the moment before decision, the pause before surrender. The viewer is invited to project personal feelings of anticipation, melancholy, or desire onto her silent vigil. In psychoanalytic terms, the shoreline becomes a metaphor for the ego boundary—where conscious life meets the deeper currents of the id. Munch’s own diary entries from this period describe experiences of intense emotional reverie by the fjords of Norway, hinting that the print may encapsulate his own moments of existential reflection.

Relation to Munch’s Oeuvre

Young Woman on the Beach fits within Munch’s broader Frieze of Life cycle, which includes works such as Melancholy (1896), Moonlight (1896), and Ashes (1894). Each piece explores variations on themes of love, loss, longing, and mortality through recurring settings—roads, shorelines, and interior thresholds. Compared to his more dramatic canvases like The Scream (1893) or Anxiety (1894), this print is quieter yet no less profound; it channels emotional intensity through subtle tonality rather than overt gesture. Munch’s experiments in printmaking influenced German Expressionists—Käthe Kollwitz, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Emil Nolde—who saw in his graphic works a model for conveying raw feeling in black and white or limited color. Young Woman on the Beach thus occupies a pivotal place in Munch’s transition from Symbolist painter to modernist print pioneer.

Reception and Critical Legacy

When first published in 1896, Young Woman on the Beach appeared in a limited edition portfolio of Munch’s woodcuts, alongside The Dance of Life (1899) and Madonna (1894–95). Collectors and critics praised its atmospheric subtlety and technical finesse, noting how Munch had expanded the expressive possibilities of relief printmaking. In the decades that followed, the print was exhibited in major retrospectives of Munch’s work—in Oslo, Berlin, and New York—and scholars highlighted its significance in his graphic output. Contemporary printmakers continue to study its layered blocks and hand-applied color as exemplary of a hybrid approach that bridges painting and print. As digital and hand-pulled print media evolve, Young Woman on the Beach remains a touchstone for artists seeking to convey mood and narrative through pared-down means.

Conservation and Provenance

Original impressions of Young Woman on the Beach are held by institutions such as the Munch Museum (Oslo), the British Museum (London), and the Museum of Modern Art (New York). Conservation work focuses on stabilizing the delicate Japanese-style paper, which is prone to embrittlement over time, and protecting the hand-applied colors from fading under light exposure. Technical studies—using infrared reflectography and microscopy—have revealed Munch’s carving marks and inking variations, offering insight into his process. Early impressions passed through private Scandinavian collectors before being acquired by public museums in the early 20th century, underscoring the work’s high esteem among both artists and connoisseurs.

Broader Cultural Significance

Beyond art-historical circles, Young Woman on the Beach resonates as a universal image of contemplation and psychological threshold. Writers and poets have referenced its motif of the solitary observer at water’s edge to convey states of yearning or transition. In film and photography, the backlit silhouette by the shore recalls Munch’s composition, signaling moments of reflective pause or emotional suspense. In contemporary wellness and design, the print’s interplay of cool and warm tones—and its evocation of liminal light—has inspired color palettes and spatial arrangements intended to foster calm and introspection. Its enduring relevance lies in its ability to evoke the universal human experience of standing between past and future, known and unknown.

Conclusion

Young Woman on the Beach (1896) stands as a testament to Edvard Munch’s ability to distill profound emotional states into deceptively simple graphic forms. Through a masterful combination of composition, subtle color layering, and innovative woodcut techniques, Munch creates a scene pregnant with psychological tension—a solitary figure poised at the threshold of inner depths and outer expanse. As both a milestone in the history of modern printmaking and a timeless meditation on solitude and longing, Young Woman on the Beach continues to invite viewers into its quiet, introspective world, where each whisper of wave and shift of light echoes the stirrings of the human soul.