Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

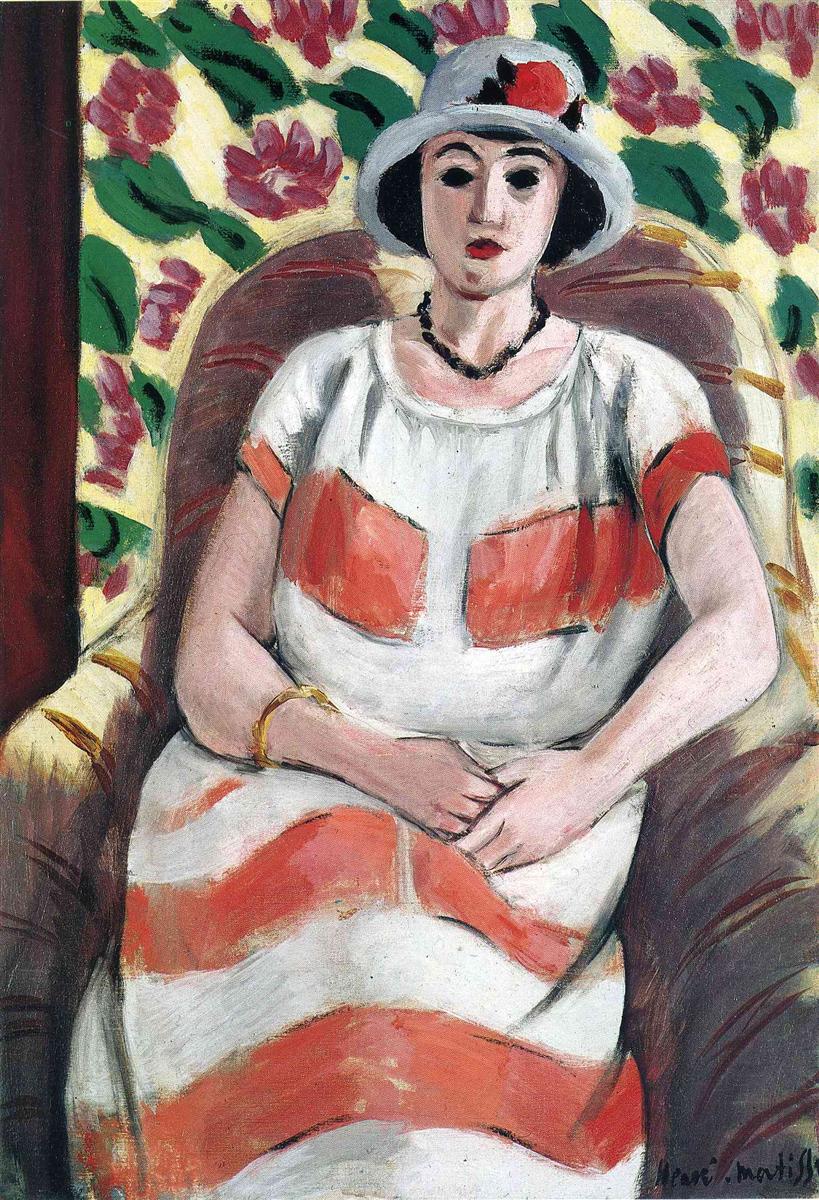

Henri Matisse’s “Young Woman in Pink” (1923) is a radiant portrait from his Nice period, painted when the artist had perfected a language of calm luminosity, patterned interiors, and poised human presence. A seated woman occupies an armchair set against a wallpaper of cream yellow scattered with dark green leaves and rose-pink blossoms. She wears a white dress punctuated by broad pink bands, a cloche hat tipped with a red accent, a black bead necklace, and a thin gold bracelet. The picture is intimate but not private; decorative yet disciplined. In it, Matisse transforms the everyday elegance of a modern sitter into a measured harmony of color and shape that still feels fresh a century later.

Historical Context

After 1917, Matisse worked for long stretches in Nice, a setting whose mild Mediterranean light supported his shift from the jolt of Fauvism to a quieter, orchestral modernism. The Nice years are defined by interiors—odalisques, readers, musicians—staged among screens, carpets, and flowers. Portraiture remained essential, but the emphasis moved from psychological probing to a balance of figure and décor. Painted in 1923, “Young Woman in Pink” stands at the center of this evolution. Instead of the theatrical props of his odalisques, Matisse chooses bourgeois accessories—a cloche hat, necklace, bracelet—and integrates them into the same decorative logic that governs his rooms. The result is a portrait that is modern in both spirit and style: modest, urbane, and fully pictorial.

Composition and Structure

The sitter is placed frontally, cropped at mid-thigh, and held within the curved embrace of the armchair. Her forearms rest lightly in her lap, fingers intertwined in a relaxed knot. This triangular basket of hands stabilizes the lower half, while the head, slightly tilted, and the hat’s circular brim supply a calm counter-rhythm above. The armchair’s rounded sides, brushed with ocher and mauve, echo the curve of shoulders and hat, gently containing the figure without smothering her. Matisse braces this central monument with two strong vertical strips at the edges: a deep burgundy band to the left (a drape or jamb) and a column of floral wallpaper to the right. These uprights function like stage flats, keeping the composition from drifting and offering a frame within the frame.

Pattern as Architecture

The wallpaper is more than background; it is the architectural field of the painting. Its repeat of leafy green and rose-pink flower clusters across a pale yellow ground produces a soft, steady pulse. The figure’s dress answers with its own pattern—a sequence of broad pink bars across bodice and skirt. By setting stripe against blossom, Matisse creates a counterpoint that drives the eye in measured loops: flowers to bands, bands back to flowers. The armchair features its own subdued striping, bridging wallpaper and dress. This three-part conversation among patterns is typical of the Nice period: ornament doesn’t decorate the figure from the outside; it integrates her from within, turning the whole surface into a democratic field where every element plays its role.

Color Climate

Color provides the picture’s climate. The yellow wall warms the room like sunlight; the green leaves cool it; the rose-pink blossoms supply a lyrical middle register. These hues reappear on the sitter in moderated form: pink blocks and bands on the dress, a red accent on the hat, a faint rose tint in cheeks and lips. The black necklace and the dark eyes act as grounding notes, preventing the palette from becoming sugary. Flesh is modeled with pearly creams touched by gray-violet shadows along the jaw and inner arm; these cools keep the skin luminous against the warm wall and chair. The bracelet’s small gold flare and the hat’s red flower serve as precise, sparkling accents that focus attention and calibrate the temperature of nearby colors.

Drawing and the Economy of Line

Matisse’s drawing is spare and exact. The face is assembled from a few confident strokes: arched brows, succinct lids, a small planar nose, and a compact vermilion mouth. There is no fussy modeling—just enough tonal shift to suggest the turn of cheek and the shadow beneath the hat’s brim. The hands, notoriously difficult for portraitists, are simplified into gently interlocked shapes that remain descriptive without stealing the scene. The dress’s bands are pulled with firm, slightly frayed edges that keep them alive; they sit on the cloth rather than sinking into it. Throughout the picture, contour tightens at the places where we need it—the jaw, wrist, hat brim—and relaxes elsewhere, preserving freshness and flow.

Light Without Drama

Illumination arrives as ambient glow rather than theatrical spot. There are no heavy cast shadows to pin the sitter to the chair. Instead, the room breathes: warmer light in the wall and chair; cooler notes in the folds of the dress; a soft dark under the chin; a milky highlight on the hat’s rim. This even light is central to the Nice period’s ethos. It allows color to carry expression and keeps the picture poised. The sitter seems present in our air, not staged on a deep set.

The Modern Sitter

Unlike the odalisques’ exoticized costume, this sitter’s cloche hat and striped dress anchor her in the modern 1920s. The hat’s rounded profile compresses the head into a pleasing oval, flattering the frontal pose and echoing the curve of the chair. The necklace and bracelet add urban polish while doing structural work: the necklace’s black beads gently punctuate the broad, pale plane of the chest, and the bracelet provides a small golden fulcrum that links the forearm to the hands. Matisse treats these accessories as notes in his score—never anecdotal, always functional.

Space by Layers, Not Perspective

Depth is achieved through layering rather than through strict vanishing points. The chair sits firmly in front of the wall; the figure sits in the chair; the left burgundy strip overlaps everything like a curtain drawn into the frame. This approach keeps us at conversational distance from the sitter. We feel near enough to touch the cloth’s roughness, the cool felt of the hat, the smooth bead of the necklace. The space is intimate without being confessional.

Rhythm and Tempo

The painting’s rhythm is set by repeating shapes: the blossoms’ rounded silhouettes; the chair’s arcs; the hat’s circle; the broad horizontal bands across the dress. These rounded forms are crossed by a few straight lines—the arms’ edges, the dress’s seams, the burgundy strip at left—preventing the rhythm from becoming lulling. The tempo is slow and assured, matching the sitter’s composure. You sense the measured time of a sitting—start, settle, hold—translated into visual cadence.

Brushwork and Material Presence

Matisse’s surface never hides how it was made. In the wallpaper, flowers are stamped with brisk, opaque touches, edges feathering where the brush lifts. The chair’s stripes are dragged wet-into-wet, leaving soft, mingled transitions that suggest upholstery nap. The dress’s pink bands are laid with determined, slightly dry strokes that let the ground flicker through, keeping the fabric breathing. In the face and hands, the paint thins and thickens with meticulous restraint—enough to describe, never so much as to harden. This varied touch keeps the portrait tactile and alive, poised between design and sensation.

Psychology by Poise, Not Drama

Matisse avoids narrative psychology. The expression is reserved, the eyes simplified, the mouth closed. Yet mood permeates the canvas: a quiet self-possession, the dignity of someone prepared to be seen without performing. The long horizontal of the mouth, the direct alignment of head and torso, and the restful basket of hands all contribute to this steadiness. The result is not coldness but calm; the viewer is invited to linger in a space where attention itself is the subject.

Dialogues with Other Works of 1923

Seen alongside the odalisques and reading women from 1923, “Young Woman in Pink” appears more urban and less theatrical. Décor is still vital, but the patterns are simpler—a single floral wallpaper rather than a room filled with screens and carpets. The palette pivots around pinks rather than the saturated reds of many Nice interiors, giving the picture a gentle buoyancy. The frontal pose and the hat echo Matisse’s fascination with iconic formats: a human figure tuned to design, stripped of anecdote, and intensified by ornamental rhyme.

The Role of Pink

The title directs us to pink, and Matisse treats it as more than a hue—pink becomes subject. It appears as blunt bands on the dress, as flushed notes in the cheek and lips, and as blossom color multiplied across the wall. Because the chair and wall are warm, he leavens pink with cools—pearl in the flesh, gray-violet in shadow, and green in the leaves—so the color never cloys. Instead, pink acts like a melody carried by different instruments across the picture: bold in the dress, lyrical in the flowers, whispered in the face. This orchestration shows Matisse’s command of color not as decoration but as structure.

Feminine Modernity

The cloche, stripes, bracelet, and necklace point to contemporary fashion, but Matisse avoids illustration. He is interested in how modernity looks when translated into paint: distilled shapes, clean rhythms, and colors that feel both tender and strong. The sitter’s clothes are stylish yet reduced to elemental forms—circles, bands, arcs—so they can join the painting’s larger harmony. In this way, “Young Woman in Pink” becomes a portrait of style itself, of the 1920s’ crisp clarity softened by decorative pleasure.

How to Look, Slowly

Begin with the hat’s red accent and feel how it anchors the top of the composition. Let your eye trace the brim’s ellipse and descend to the necklace’s small, regular beats. Follow the pink bands across the bodice to the folded hands; pause at the bracelet’s gold flash; then ride the broader pink stripes of the skirt outward to the chair arms. Step into the wallpaper’s blossoms and notice how each flower mirrors (but never duplicates) the dress’s pink. Return to the face—brows, lids, mouth—and feel how few marks carry the whole presence. This slow circuit reveals the painting’s logic: ornament as rhythm, pink as melody, poise as tempo.

Legacy and Relevance

“Young Woman in Pink” shows why Matisse’s Nice period remains influential for painters and designers alike. It demonstrates how to reconcile pattern with portraiture, how to substitute ambient light for dramatic effects, and how to build psychological presence from posture and chromatic climate rather than from narrative detail. The painting also proposes an ethic for looking today: to attend to color carefully, to accept serenity as a modern value, and to recognize that domestic elegance can bear the weight of art.

Conclusion

Matisse’s “Young Woman in Pink” is a compact symphony of rounded forms, floral rhythms, and carefully tuned color. Without theatrics, it achieves a poised intensity: the sitter’s modern accessories, the wallpaper’s gentle pulse, the dress’s pink bars, and the armchair’s soft arcs all conspire to hold attention in a steady, luminous chord. It is a portrait not merely of a person, but of a way of seeing—one that converts the ordinary into a quietly persuasive harmony. A century on, the canvas still offers what Matisse sought: a restful, radiant space where the eye finds balance and the spirit, a gentle lift.