Image source: wikiart.org

A First Look at the Scene

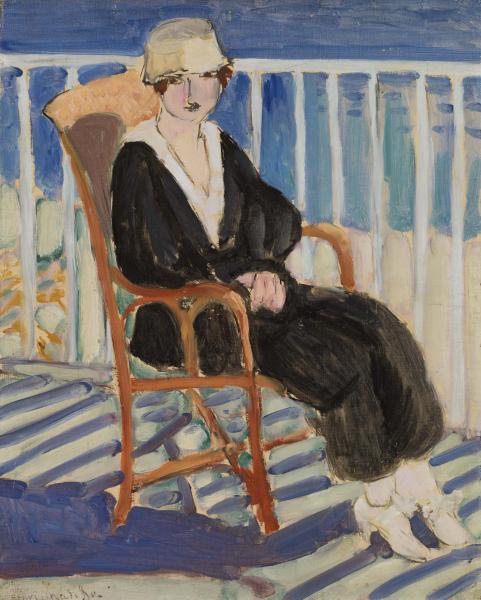

Henri Matisse’s “Young Girl on a Balcony over the Ocean” presents a poised, modern figure seated on a wicker chair, framed by a white balustrade and the blue breathing space of sea and sky. The composition is simple—girl, chair, rail, horizon—yet it feels charged. Diagonal blue shadows rake across the floorboards like musical bars; the baluster spindles beat a vertical rhythm; beyond them, blue bands of water and atmosphere melt into one another. The sitter wears a black dress with a white V-neck, a pale cloche-like hat, and white shoes whose highlights echo the bright rails. Everything is reduced to large, legible relations of color and line. With a few tuned tones—lapis, milk-white, soft peach, and the living black of dress and contours—Matisse converts an ordinary balcony into a climate of calm.

The Moment in Matisse’s Career

The date, 1918, matters. Matisse had just pivoted from the carved severity of his mid-1910s canvases to the tempered light of the Côte d’Azur. The Nice years would bring interiors, windows, and odalisques; but first came pictures like this, where he tested a new key: shallow, breathable space; tuned color rather than blazing complement; black used as a positive, structuring pigment; and everyday subjects composed with classical clarity. The earlier Fauve heat is present only as memory; here the drama is the steadiness of Mediterranean light and the serenity of measured form after a decade of upheaval.

Composition as Architecture

The composition is built from a handful of strong gears. Horizontals—seat rail, balcony rail, sea horizon—calm the eye. Verticals—the evenly spaced balusters—hold the central band like a picket choir. Diagonals—those long blue shadows cast by the railing—tilt across the floor and inject movement without breaking the calm. The girl sits slightly off-center but commands the rectangle because her dark dress forms the largest singular mass. The wicker chair’s warm arcs cuff the figure, adding a supple counter-shape among the rectilinear elements. Seen as pure design, the painting is a duet between straight lines (architecture, sea) and curved ones (body, chair).

The Balcony Motif and the Idea of Threshold

Matisse’s Nice period loves thresholds: windows, balconies, screens—the places where interior calm meets exterior air. This painting is a lucid statement of that theme. The sitter is neither entirely indoors nor outdoors; the balcony is a platform for contemplation. The white balusters stake out a permeable barrier: they separate the figure from the ocean while letting the blue pass through as light and color. In Matisse’s language, thresholds are not merely places; they are instruments that tune the relationship between world and design.

Palette: Tuned Blues, Living Blacks, and Quiet Warmth

Color does the emotional work with the soft authority of a chamber piece. The balcony’s shadows are cool, slightly violet blues; the water beyond deepens from turquoise toward indigo; the sky is a milkier, brushed blue. These cools are balanced by restrained warmth: the peachy back of the wicker, the sitter’s flesh notes, and the faint ochre on the hat. The dress and choker are black, but Matisse handles black as living pigment, not absence—it shifts from brown-black to blue-black depending on neighbors. Because saturation is moderated, temperature shifts carry light: the white of the rail and collar is not clinical but sunlit; blues bloom where they meet those whites; flesh glows because it sits between cool sea and warm chair.

Black as a Positive Color

Matisse is a master of black used as color. Here, black anchors the composition: it gives the dress weight, binds the head to the shoulders via the ribbon at the neck, and draws the eyes and mouth with calligraphic precision. Where black meets white—collar against garment, shoes against shadow—the contrast sings; where it meets blue, it moderates and cools; against the peach of the chair it warms. These blacks are the composition’s bass line, the steady frequency under the blues.

Brushwork and the Visible Pace of Making

The painting keeps faith with the act of painting. The sea is brushed in horizontal passes that leave ridges, like ripples of wind; the balusters are laid with sure, vertical strokes that thicken near joints; shadows are swept diagonally with loaded bristles that deposit pigment unevenly, producing a striped vibration on the floor. The sitter’s dress is a field of varied blacks built from broad, directional strokes; the hat is a quick, creamy cap of paint with a darker band; facial features are minimal but decisive—two dark almonds and a pink, abbreviated mouth. Nothing is overpolished, and that visible making is part of the image’s modernity.

Space Held Close to the Plane

Depth in the picture is believable yet shallow. Overlap does most of the work: chair in front of girl, girl in front of rail, rail in front of sea. Value shifts seal the illusion—the nearer blues are stronger; the horizon’s band is cooler and lighter. But Matisse refuses theatrical perspective. The figure sits, and the sea sits, on the same stage: the picture plane. This commitment allows the painting to perform as both scene and decorative object—world and woven surface at once.

The Figure: Fashion, Poise, and Psychology

The young girl is modern without being anecdotal. The cloche-like hat, black dress with white V-neck, and white slippers belong to the present tense of 1918 but also function as compositional devices: pale hat against blue sky; white collar piercing the dark dress; bright shoes stepping into the cool shade. Her hands clasp loosely; her posture is composed, slightly turned, calm rather than coy. The head tilts marginally as if to test the air. Matisse resists overt psychology; the portrait’s feeling arrives through relation—how the black mass sits within the white pickets and blues, how warmth gathers behind her in the wicker, how the angled shadows tease the stillness of her pose.

Shadows as Music

Those diagonal shadows are the painting’s rhythm section. Cast by the morning or late-afternoon sun low over the sea, they run across the deck like a set of long, parallel notes. Their value varies as the brush loads and empties; their blue changes temperature as it crosses floorboards and meets reflected sky. They convert the balcony from simple platform into time and tempo. With the regular verticals of the rails, the shadows’ obliques create syncopation—a quiet swing that keeps the composition breathing.

The Chair’s Role: Warm Counterform and Human Scale

The wicker chair is more than a prop; it is a warm counterform and an index of scale. Its back flares like a shell, and its caramel tone mediates between cool sea and dark dress. The openwork pattern near the girl’s shoulder softens the left edge and insinuates a decorative motif without stealing focus. Its curved arms encircle the midsection of the girl’s black silhouette, giving the central mass a gentle, human contour amid the straight rails. The chair also sets the balcony’s dimension: we infer the depth of the deck and the height of the railing because the chair belongs to a body we understand.

Pattern Without Clutter

Matisse permits two kinds of pattern—structural and suggestive. Structural pattern is the railing’s repeated pickets and their cast shadows. Suggestive pattern appears as color patches beyond the rails at lower left, where pebbles or beach umbrellas flicker. He keeps this background notation loose and low-contrast so it reads as the sea-edge’s texture rather than as narrative detail. The result is a maximum of graphic clarity with a minimum of descriptive burden.

Edges, Joins, and the Craft of Meeting

Edges are tailored to what they represent. Where white rail meets blue sea, the seam is crisp: sunlit wood against distance. Where blue shadow crosses floor, the edges soften as bristles skate over texture. Where cheek meets hat, a warm halo blooms—wet paint tugged into neighbor—signaling the head’s roundness without elaborate modeling. The dress’s black meets the chair with a firm contour, anchoring mass; meets the rail with a softer edge, letting light refract into fabric. These varied joins keep the simplified forms from reading like pasted cutouts and seat the figure convincingly in air.

Evidence of Revision and the Courage to Stop

Close looking reveals pentimenti: a rail restated, the shadow grid corrected at the edge, the chair arm retraced after the dress was darkened, the outline of the hat clarified with a later pass of blue. Matisse does not sand away these traces. They are the record of search and correction—the visible proof that the composition’s inevitability was earned. He stops when relations ring true, not when surfaces are cosmetically smooth.

Dialogues with Tradition

The balcony scene nods to a modern lineage: Manet’s “The Balcony,” the Impressionists’ promenades, and Matisse’s own “Open Window” motif from earlier years. But instead of figure-as-spectacle or optical flicker, he offers poise and structure: a figure nested within a design of rails, shadows, and sea bands. Japanese print sensibility murmurs in the flat color fields and bold contour; Cézanne’s lesson echoes in the planar treatment of the head and dress. Yet the total is unmistakably Matisse: serenity achieved through a handful of true relations.

Relationship to Contemporaneous Works

Compared with “The Violinist at the Window” from the same year, this canvas flips orientation and mood: the musician’s interior diagonals become outdoor ones; the ochres and reds become a cooler coastal chord. Set beside “The Black Shawl,” it swaps recline for upright and patterned textile for the structural music of cast shadows. With the early Nice landscapes, it shares the positive use of black and a shallow depth that keeps the viewer near the surface. Together these works map a vocabulary—threshold, tuned palette, structural black, rhythmic repetition—that Matisse would refine throughout the 1920s.

The Ethics of Looking

The painting offers companionship without trespass. The girl is not an object of scrutiny; her gaze is poised but withheld, her body fully clothed, her hands folded. The vantage is respectful—slightly below eye level, a fellow sitter on the balcony rather than a voyeur. The true subject is not her identity but the climate she inhabits. This restraint is key to the work’s lasting ease: we are invited to share the air, not to possess the figure.

How to Look: A Guided Circuit

Enter at the bright shoes and feel the cool blue shadow wash over them. Follow that diagonal across the floor until it meets the chair leg; climb the warm arc of the wicker to the sitter’s folded hands; cross the white V of the collar into the black field of the dress; lift to the pale hat where a lozenge of light kisses the brim. Step through the pickets into the sea’s horizontal bands—near blues darker, far blues lighter—and rise to the milky sky. Drift back down along a baluster to another blue shadow and repeat the loop. The painting performs like a quiet song on repeat.

Why It Still Feels Contemporary

A century later, the canvas looks fresh because its clarity aligns with modern eyes. Big shapes read at a glance; the palette is sophisticated rather than loud; process is visible and honest; space remains close to the plane in a way that suits photographic and graphic sensibilities. Most of all, the painting trusts a few exact relations—black mass against white rails, blue shadows across ground, human curve against architecture—to carry mood. That trust is modern in the best sense: rigorous, humane, and generous.

Conclusion: Balance Composed from Air and Line

“Young Girl on a Balcony over the Ocean” is a compact manifesto for Matisse’s early Nice period. With minimal means—a chair, a figure, a railing, a slice of sea—he composes an image that steadies the breath. Blues whisper through whites; blacks anchor; warmth glows from wicker and skin. The diagonals of shadow give the piece time, the balcony sets the theme of threshold, and the sitter embodies the poised modernity Matisse sought after years of turmoil. It is not a spectacle but a cadence: a view you can live with, an hour of sea air held inside a rectangle.