Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

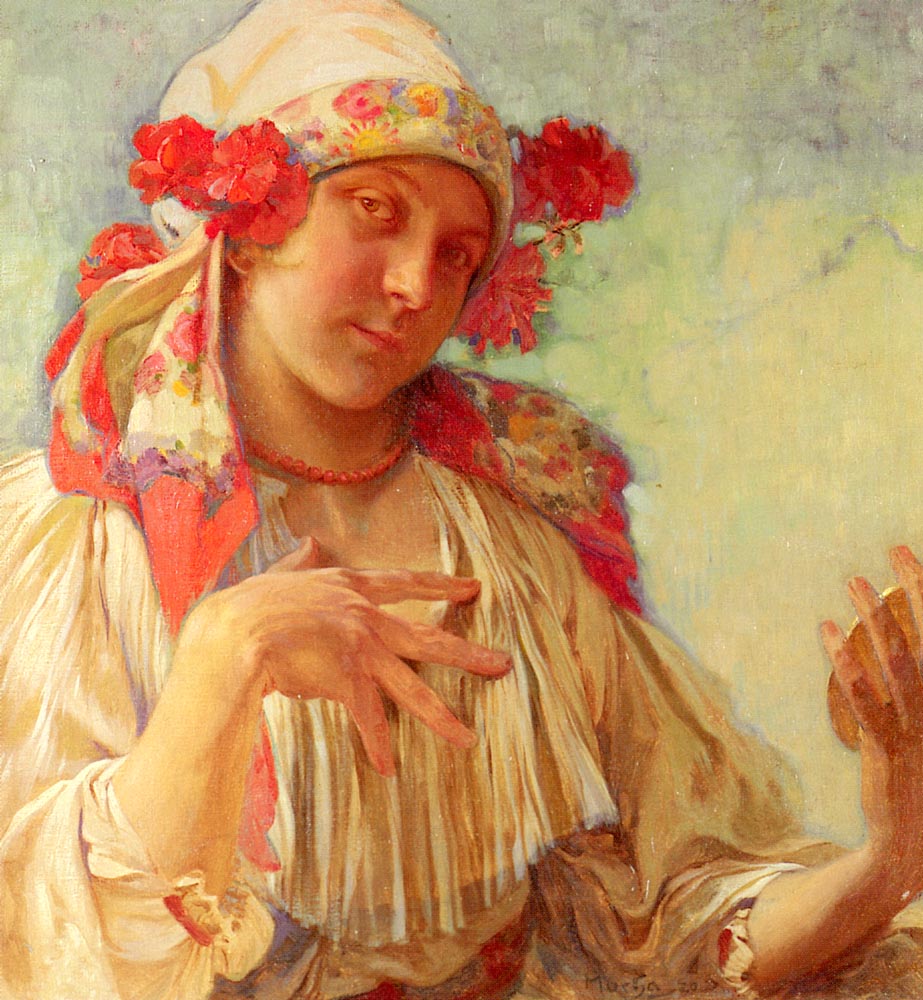

Alphonse Mucha’s “Young Girl in Moravian Costume” is an intimate oil portrait that condenses the artist’s lifelong devotion to Slavic identity, craft, and beauty into a single human encounter. Instead of the gilded halos, elongated arabesques, and tall decorative panels that made Mucha the emblem of Art Nouveau, this painting offers a young woman at close range, her head slightly cocked, her eyes alive with self-possession. She wears the distinctive kroj—the traditional dress—of Moravia: a floral headscarf knotted over a white cap, bright blossoms tucked at the ears, a coral bead necklace, and a pleated chemise whose soft folds glow under a gentle light. One hand unfurls in a graceful, dancer-like gesture while the other raises a small round object at the picture’s edge, its rim catching a thread of light. The background dissolves into a warm sky-colored field, so that costume and skin seem to bloom from the canvas. The result is both a portrait and a declaration: this is a living face of Moravia, rendered with intelligence, affection, and painterly authority.

A Portrait That Feels Like Conversation

Mucha brings the viewer close—so close that the model’s breath and warmth seem to touch the surface of the painting. The composition cuts off at the bust, cropping out any setting and turning the encounter into a conversation. The sitter’s head tilts toward us; her mouth holds the suggestion of a smile; her eyes follow ours with steady curiosity rather than coyness. In many of Mucha’s commercial posters, the woman’s gaze is a public performance, directed outward to a boulevard full of passersby. Here the gaze is private. We are not spectators of a spectacle; we are guests in the presence of a person. That difference animates everything else—the hands speak more softly, the fabric breathes instead of staging itself, and the color carries the warmth of contact rather than the flash of display.

The Theater Of Hands

The left hand unfurls in an elegant, slightly theatrical gesture, each finger described with anatomical care and a subtle play of tendons under the skin. It appears to be mid-movement: perhaps a dancer’s flourish, perhaps a conversational emphasis, perhaps the instinctive grace with which people arrange their bodies when they are being watched by someone they trust. The right hand holds a small circular object—its specific identity remains tantalizingly open. Whether a tambourine, a mirror, or a wooden hoop, it functions as a visual counterweight to the splayed left hand and as a narrative prompt. The two hands together frame the chest and face, staging the act of presentation without resorting to rhetoric. In Mucha’s work, hands are never mere accessories; they are the punctuation of a sentence written in light.

Costume As Cultural Memory

Every element of the costume arrives with meaning. The scarf’s floral band speaks to Moravian textile traditions whose motifs—roses, poppies, and wildflowers—carry the memory of fields and seasons. The white chemise, gathered into disciplined pleats, signals a craft vocabulary honed by generations; its surface is not flat but alive with the micro-architecture of folds, the habits of washing and starching, the care of hands that prepared garments for feast days. The slender necklace of coral beads sits at the base of the throat like a protective talisman; throughout Central and Eastern Europe, such beads have been prized for both beauty and symbolism, often associated with vitality and health. Mucha renders these objects lovingly, but he never lets them eclipse the person. Costume is the vessel; character is the wine.

Color That Warms Without Shouting

The palette belongs to sun and skin. Creamy whites dominate the blouse and headscarf, but they are never cold: warm ochres and soft pinks are woven through the paint to keep the fabric alive. The florals introduce saturated reds and tender violets; these hues echo in the blossoms tucked near the ears and in the coral necklace, establishing a rhythmic scattering of chromatic accents around the face. The background is a diluted blue-green that recedes without deadening, like a cloudlit sky seen through a thin veil. Mucha was a master of printed color in his lithographs; here, with oil, he proves equally adept at mixing tones that glow from within. The transitions are liquid, the shadows transparent, the highlights never chalky. Color guides us not to spectacle but to intimacy.

Light As Touch

The light in “Young Girl in Moravian Costume” is as soft and encompassing as daylight spilling from a high window. It falls gently across the forehead, knuckles, and pleats, and it turns at the curve of the cheek with the care one uses in touching another person’s face. There is little theatrical contrast; instead, the image is held together by a network of small, faithful modulations. Where the pleated blouse catches light, Mucha paints a creamy ridge tipped with a fine thread of brightness; where the hand dips into shadow, he preserves the translucency of skin by glazing rather than piling on dark pigment. The effect is tactile. We sense humidity, flesh, and textile—not a staged illumination but a living weather.

Brushwork And Surface

Close viewing reveals a painter fully in command of the medium. Broad, elastic strokes construct the larger volumes of shoulder and sleeve; smaller, calligraphic marks refine the scalloped edge of the cuff and the floral patterning of the scarf. In the face, the paint is laid down with a mix of softness and exactitude: edges are controlled but never drawn with a hard line. Mucha understands when to let the canvas show through and when to saturate it. The surface is neither brittle nor glossy; it carries the gentle sheen of oil absorbed and carefully layered. You feel the tempo of the artist’s hand shifting—slower over eyes and mouth, quicker along the scarf’s borders—like a musician moving through adagio and allegro inside the same piece.

Composition And The Architecture Of Intimacy

At first glance the composition appears loose and spontaneous, but beneath that ease lies a clear architecture. The main lines form a nested set of diagonals: the head tilts left, the scarf descends right, the left hand arcs back toward the face, and the right forearm counters toward the picture’s edge. These diagonals keep the eye circling the focal zone—the triangle of face and hands—while the background remains a tranquil field. The blossoms over the ears act like soft hinges that lock the headscarf to the head and frame the gaze. The necklace provides a small red centroid anchoring the vertical axis. Nothing feels accidental; everything contributes to an intimate choreography of attention.

Moravia In The Artist’s Imagination

For Mucha, Moravia was not merely a place; it was the spiritual seedbed of his art. He returned to regional themes repeatedly, even amid international fame in Paris and New York. Moravian costume, song, and ritual entered his work as emblems of continuity and dignity. This painting sits comfortably alongside the portraits of his children and the figures that populate the “Slav Epic.” Whereas the murals present history at monumental scale, “Young Girl in Moravian Costume” compresses that history into one person. The same love of folk ornament that ripples across the Epic’s banners now rests in a scarf’s border. The same reverence for community that animates the murals’ crowds is here focused on a single expression. The macrocosm is folded into the microcosm of a human face.

Between Poster And Portrait

Mucha’s reputation rests largely on lithographic posters whose women, framed by arabesques and botanical halos, became icons of fin-de-siècle glamour. This portrait borrows some of that vocabulary—the floral framing, the stylized elegance of the hand—but it replaces promotional allure with mutual regard. There is no product to sell, only a presence to honor. The difference is instructive. The poster’s flat color areas become, in oil, thickened fabrics with memory; the graphic arabesque becomes soft anatomy and moving light; the emblematic beauty becomes a particular person. The result lets us see the draftsmanship beneath the design and the empathy beneath the icon.

Gesture, Personality, And The Psychology Of Proximity

The subject’s personality emerges not through overt narrative but through a collection of micro-gestures. The slight tilt of the head suggests playfulness balanced by self-awareness. The raised left hand could belong to a storyteller or a singer marking time. The right hand, partly off the canvas and holding a circular object, introduces a note of mystery or expectation. Together these details create a psychology of proximity: the sitter is open but not exposed, poised but unguarded, aware of our gaze but in command of her own presence. Mucha resists both sentimentalization and idealization, allowing the person to remain wonderfully human.

The Poetics Of Ornament

Ornament in this painting is never pasted on; it grows from the structure of the scene. The floral motif of the scarf repeats in real blossoms near the ears, an echo that bridges textile and life. The red of the petals moves to the necklace and then flickers again in the cuff’s tiny stitch of color, sending a pulse through the composition. The pleats of the blouse create their own ornamental rhythm—regular yet handmade, disciplined yet soft. Mucha’s genius lies in letting ornament become a register of human activity: weaving, sewing, gathering flowers, tying knots, arranging hair. Beauty resides in those actions, and the painting preserves them without pomp.

Materials As Meaning

Seen through Mucha’s eyes, materials themselves are bearers of meaning. Linen breathes with a purity associated with feast-day garments and with the practical integrity of rural life. Coral suggests connection to trade routes and to an old belief in the gentle power of stones. Floral cottons testify to industrial dyes meeting folk taste, a modern collaboration that does not erase tradition but refreshes it. Oil paint, the medium of European high art, becomes a vehicle for honoring village craft. In this way, the picture stages a reconciliation between city and countryside, academy and home, modernity and memory.

Background As Quiet Weather

The background’s blue-green field may look plain, but it is carefully tuned. Its coolness throws the warm flesh tones forward; its softness keeps the mood contemplative rather than theatrical; its faint variations in hue resemble clouds dissolving on a summer afternoon. By refusing to locate the sitter in a specific interior or landscape, Mucha makes the portrait both personal and archetypal. We feel proximity to one woman while sensing the breadth of a culture behind her. The background is the sky of a shared world into which the sitter steps like dawn.

Light On Skin, Skin As Story

Mucha paints skin as if it were a story told in half-tones. The cheeks carry a blush that hints at recent movement; the forehead holds a higher key of light that suggests youthful elasticity; the hands display a more complex palette—peach, ivory, trace green where veins approach the surface—indicating both blood and articulation. Skin here becomes a medium of truth. It reveals the health of the sitter, the quality of the light, and the closeness between painter and model. It also mediates the painting’s ethics: nothing is polished into porcelain or heightened into melodrama. The person remains alive.

The Round Object At The Edge

The object clipped at the painting’s right edge invites speculation. Its circular rim catches light; its interior is left indistinct. As a mirror, it would suggest self-regard and the negotiation of identity; as a tambourine, it would propose sound, community, and festivity; as a wooden hoop or keepsake, it would mark the continuity of craft. Mucha’s decision to keep it ambiguous is artistically shrewd. It supplies a visual counterweight to the left hand, creates depth by pushing an object into the foreground, and opens narrative possibilities without pinning the sitter to a single role. The open meaning mirrors the open gaze.

Technique And The Discipline Of Restraint

Though luxuriant in color and texture, the painting depends on restraint. The number of elements is limited: head, hands, scarf, blouse, necklace, blossoms, object, background. Mucha invests each with attention rather than multiplying props. Within that economy, he varies edges—sharp along the fingers where expression matters, softened at the sleeve where atmosphere can take over. He grades color by glazes rather than sudden jumps, allowing light to travel through layers. The discipline becomes a form of respect. Nothing is present that the sitter does not need to be fully herself.

A Humanist Vision For Modern Eyes

“Young Girl in Moravian Costume” reads as timely because it honors identity as lived reality rather than spectacle. In an era—Mucha’s and ours—when images of women are often pressed into commercial fantasy, this painting insists on dignity rooted in community and craft. It invites viewers to recognize the beauty of cultural continuity without reducing the person to a symbol. It allows a regional costume to be both specific and radiant, a way of being rather than a prop. In so doing, the work models a humanism that suits the present: attentive, curious, and generous.

How To Look, Slowly

The painting rewards slow attention. Begin at the eyes and sense the equilibrium between welcome and reserve. Travel to the red beads and notice how their tiny ellipses control the scale of the whole face. Follow the pleats downward and feel their changing cadence—tight near the collar, looser where the blouse settles into shadow. Return to the hands: watch the light slide along the fingers, pause at a knuckle, and release toward the wrist. Drift outward to the patterned scarf and compare painted blossoms with the fresh ones at the ears. Finally, allow the blue-green background to reset your gaze, then start again. Each circuit deepens the encounter, as if the sitter had said one more thing.

Legacy

Placed within Mucha’s broader career, this canvas demonstrates how the figure who defined a decorative epoch also possessed the classical virtues of portraiture: empathy, structure, and touch. It complements the grand cultural statements of the “Slav Epic” with a personal testimony; it converses with the poster triumphs by revealing the artist’s hand at unmediated scale. Above all, it preserves a face and a fabric of life that might otherwise fade. The young woman’s look—poised, alert, and slightly amused—crosses a century as if it were a morning’s walk.

Conclusion

“Young Girl in Moravian Costume” distills Alphonse Mucha’s art to its human core. The painting holds in balance the sensuous and the sincere, the ornamental and the observed, the regional and the universal. It turns a traditional garment into living color, a set of gestures into personality, and a close vantage into intimacy. In the tender topography of hands and pleats, petals and beads, we witness not only a sitter but a culture carried forward by affection and craft. Mucha offers no slogan, no allegorical label—only a person met with attention. That is why the portrait endures, and why returning to it feels like returning to someone we know.