Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

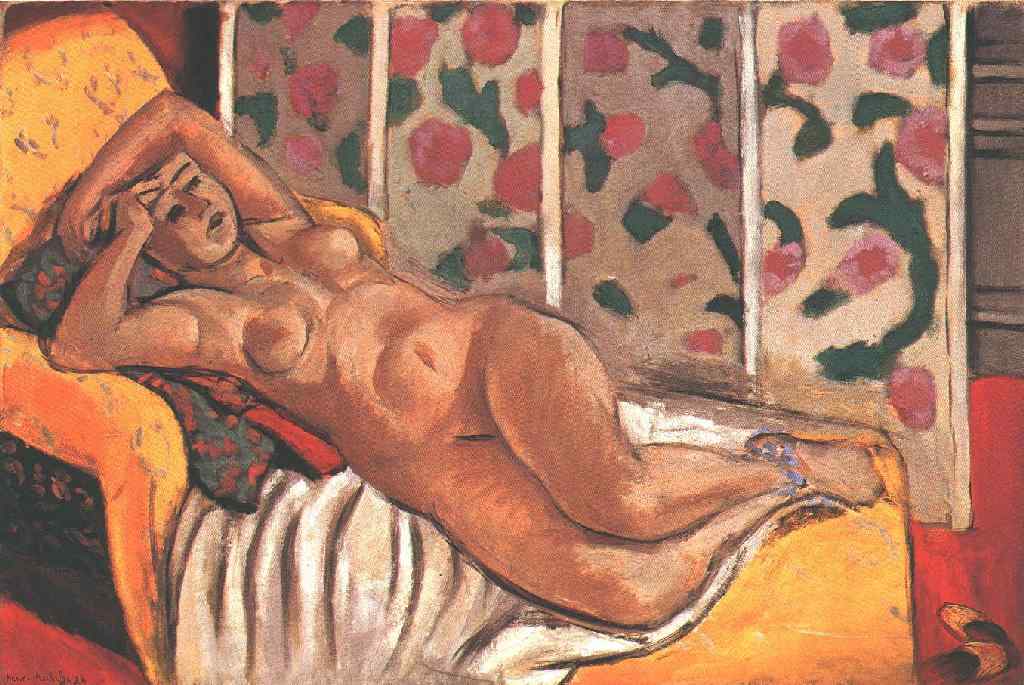

Henri Matisse’s “Yellow Odalisque” (1926) is a luminous summation of the Nice period, when the artist recast the studio as a stage for color, pattern, and poise. A reclining nude stretches across a saffron couch, the body described by supple contours and a warm, glowing gamut of apricot, rose, and pearl. Behind her, a screen of floral panels presses forward like a painted tapestry, its pinks and bottle-green leaves rhythmically scattered across a soft gray ground. A fold of white drapery pools beneath the model and slides toward the foreground in long, silvery waves. Everything is close to the picture plane; everything participates in a coherent chord keyed to yellow. The painting does not tell a story so much as it composes a mood—relaxed, alert, and modern—using the simplest, most exact means.

The Nice Period And The Decorative Intelligence

By 1926 Matisse had converted the early audacity of Fauvism into a mature decorative classicism. In Nice he worked in rooms of filtered Mediterranean light, arranging models among textiles, screens, and a few well-chosen props. The odalisque was his most flexible studio motif, granting permission for languid poses and abundant patterns without obliging melodramatic narrative. In “Yellow Odalisque,” the subject becomes a vehicle for an idea: that calm can be built from strong color and assertive drawing when intervals are tuned precisely. The painting’s discipline is felt in how each part—body, couch, screen, drapery—takes just enough space to keep the whole breathing.

Composition As A Long, Reclining Arc

The structure rests on a sweeping diagonal that runs from the model’s raised hands at the left through her breast and abdomen to the bent knee near the right edge. That diagonal is answered by two stabilizing systems: the horizontal ledges of the couch and the vertical stiles of the floral screen. Together they weave a firm lattice beneath the languor. Matisse places the head low, almost level with the torso, so the face becomes part of the reclining phrase rather than an isolated portrait. A narrow strip of red at the extreme right acts like a final bar line, arresting the diagonal’s flow before it spills off the canvas. The white drape repeats the diagonal with a gentler tempo, binding the figure to the couch the way a melody is bound to its accompaniment.

Yellow As Architecture And Atmosphere

Color supplies the architecture. Yellow is the room’s climate: walls of upholstery glow with saffron and ochre, while paler creams lift around the edges where light passes through fabric. This radiant field warms the skin without absorbing it. The figure’s flesh is made of apricot and rose moderated by cool gray half-tones, especially along the ribs and underarm where light reflects from sheet and screen. The floral panels contribute a cool counter-register—green leaves, pink petals, and dusty grays—that keeps the chord from overheating. White is not an inert neutral but a conductor: the drapery gathers reflections of yellow and green, turning slightly blue where it retreats into shadow. Blacks are used sparingly to articulate features, navel, and a few critical joins; they steady the palette without dragging it down.

Pattern, Flatness, And The Press Of The Screen

The screen behind the model is more than decoration. Its repeating floral emblems establish a steady beat that measures the surface. Because the panels are rendered as flat planes with crisp uprights, they press forward toward the picture plane, converting the room into a tapestry-like stage. This productive flatness is central to the Nice period: the painting keeps just enough depth to seat the body on the couch while making sure all the important drama—color against color, curve against grid—happens on the surface. The floral pattern also changes the mood of yellow; against gray-green, the saffron warms without shouting.

Drawing And The Breathing Contour

Matisse’s contour is frank and exact. The line along the torso thickens over the hip, slackens across the belly, and tightens again near the shoulder, like a phrase spoken with modulated emphasis. The face is a mask built from a few planes: dark hairline, precise brows, a simple nose, and a compacted mouth whose red repeats elsewhere in the couch and right margin. The hands—often over-described by lesser painters—are here reduced to articulated shapes that do the job of opening the chest and lengthening the arc of the pose. Even the screen’s uprights and floral silhouettes are drawn with a living edge; they are not mechanical repeats but hand-tuned measures that keep the surface alive.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

The canvas is suffused with the soft, bouncing light of Nice. Shadows rarely drop to black; they are chromatic—violet in the drapery’s folds, olive on the couch’s inner seams, cool gray along the flank. Highlights are placed deliberately: a milky lick over the shoulder, a warmer flash at the knee, soft gleams on the sheet’s ridges. Because the light is diffused rather than theatrical, the body’s form emerges through temperature shifts rather than harsh contrast. This approach allows the color to carry modeling and preserves the painting’s overall serenity.

The White Drape As Pictorial Glue

The drape is the hinge that binds figure to setting. Its cool whites pick up reflections from both the yellow couch and the green-gray screen, knitting the palette together. Matisse paints it with long, confident strokes that follow the gravitational fall of cloth; ridges of paint create real tactility that the eye reads as nap and weight. Where the drape crosses the belly, it thins to a veil, letting the warm flesh tone breathe through; where it piles at the hips and laps over the couch, it thickens and cools. Without this intelligent cloth, yellow might swallow the body or the floral field might detach. With it, the room becomes one continuous chord.

Flesh As Warm Geometry

Matisse refuses anatomical fuss. The body is rendered as a series of large, warm forms—a sphere of shoulder, the long cylinder of torso, the turning ovoid of thigh—joined by transitions that are almost architectural in their clarity. The line across the stomach locks into the diagonal of the pose, while the broad plane of the hip catches yellow reflections that fold the figure deeper into the setting. Modeling is subordinated to silhouette; what matters is that the body read instantly amid saturated color. That clarity grants the figure modern agency: she stabilizes the room by being a decisive shape rather than a fragile illusion.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

Matisse often spoke of painting in musical terms, and “Yellow Odalisque” proposes a clear tempo. The screen’s floral repeats provide the steady meter; the drapery supplies legato phrases; the long diagonal of the nude is the melody; and small color accents—red strip at right, dark green flecks, rose petals—are syncopations that keep the chord alert. The eye moves in composed circuits: hands to brow, brow to breast, breast to belly, belly to knee, then across the sheet to repeat. Each loop reveals fresh correspondences: a pink petal echoing the lip, a green leaf recruiting a cool shadow on the drape, a gray seam in the screen matching the half-tone along the ribs. The painting’s generosity lies in these repeated discoveries.

Orientalism Reconsidered And Redirected

The term “odalisque” carries a long history of European fantasy. Matisse acknowledges the motif—reclining pose, patterned screens, jewelry—then redirects it. The model’s modern haircut, the honest studio light, and the democratic treatment of figure and furniture remove the painting from voyeuristic spectacle. Here the “exotic” has migrated into color and pattern, domains that apply equally to body, couch, and screen. The result is not a narrative of elsewhere but a local experiment in harmony. Pleasure is present, but it is formal, rigorous, and ethical.

Space, Depth, And The Short Leash

Depth is kept on a short leash. The couch tilts toward us; the screen presses close; the body occupies a shallow trough of space just deep enough to breathe. Overlaps—arm over brow, thigh over sheet, drapery under hip—do the minimal work needed to persuade. This deliberate compression brings color relations and contour decisions to the front, where they can be sensed immediately. The picture is not a window; it is a surface in which forms interlock. That is why it remains fresh: you are invited to read relations rather than chase illusion.

Tactile Intelligence And Evidence Of Process

Close looking discloses the painting’s time. A contour along the thigh has been shifted and softened; a petal in the screen was repainted to pick up the cadence; the drape shows thin scumbles over thicker runs where Matisse adjusted weight and temperature. These pentimenti do not disturb the calm; they deepen it. They show that serenity is a worked achievement: the chord we hear was tuned, not simply found. Material presence—the drag of bristles, the slight ridge of a highlight—grounds the image in the reality of paint, which, paradoxically, makes the room feel more palpable.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Yellow Odalisque” sits in lively conversation with its neighbors. It shares with “Odalisque, Harmony in Red” the horizontal pose and the logic of a dominant color countered by cool accents, yet here yellow rather than red sets the key, yielding a sunnier, more Mediterranean chord. Compared with “Reclining Odalisque” against the diamond wall, the present canvas softens geometry into floral rhythm and trades turquoise furniture for an unbroken, glowing couch. With still lifes like “The Pink Tablecloth,” it shares pearly light and the conviction that a few exact notes can animate a quiet field. Anticipating the late cut-outs, the figure already reads as a single, decisive silhouette set into flat pattern.

Psychological Tone And Viewer Experience

Despite the saturated palette, the psychological register is unforced. The model’s face—eyes closed or gently lowered, mouth at rest—suggests inwardness, even concentration. She does not perform; she occupies. That tone affects the viewer’s pace. The painting welcomes slow looking; it creates a climate where the eye can linger on a seam, a fold, a cool note traveling through white, without being harried by narrative or spectacle. The experience is hospitable: strong color serves calm rather than clamor.

Why The Painting Endures

The canvas endures because its pleasures are structural and renewable. Each return yields a new hinge: a yellow reflection kindling on the ribcage, a green leaf aligning with a cool drapery shadow, a rose petal recruiting the small redness at the lip, a gray seam echoing the contour at the jaw. None of these discoveries diminishes the first impression of harmony; they deepen it. The painting is built to keep giving because its order rests on relations that remain interesting under prolonged attention.

Conclusion

“Yellow Odalisque” is a serene manifesto of Matisse’s Nice period. A reclining body, a radiant yellow couch, a floral screen, and a pool of white cloth are arranged so that color becomes architecture, pattern becomes grammar, and contour becomes breath. Space is shallow but sufficient; light is soft yet clarifying. The picture demonstrates how strong color can be domesticated into calm without losing vigor, and how a historical motif can be modernized by distributing dignity evenly across figure and ground. It is a chamber of sustained sensation—sun-warmed, softly lit, composed for the long gaze.