Image source: artvee.com

August Babberger’s Women in the Countryside is a captivating and enigmatic work that fuses abstraction, symbolism, and spirituality in a way that is both personal and universal. Painted in the early 20th century by the German expressionist and muralist, this piece evokes a mystical harmony between the feminine presence and the natural world. With its abstracted figures, bold brushwork, and dreamlike palette, Babberger’s painting stands as a unique statement within German Expressionism, diverging from the anguish of urban modernity and embracing a lyrical, almost sacred, view of rural life.

In this comprehensive analysis, we will explore the painting’s composition, stylistic elements, color usage, thematic resonance, and its place within Babberger’s body of work and German Expressionist art history. We will also consider how this piece speaks to broader ideas of femininity, spirituality, and the emotional landscape of the countryside.

The Artist: August Babberger and Expressionist Spirituality

August Babberger (1885–1936) was a German painter associated with Expressionism, a movement that sought to capture subjective experience over objective reality. Unlike some of his contemporaries who focused on urban angst or political critique, Babberger often turned to spiritual and mythological themes, infusing his work with a transcendent atmosphere.

A professor at the Karlsruhe Academy and an artist heavily involved in mural painting, Babberger’s works often straddled the line between decorative abstraction and psychological depth. He was deeply influenced by religious iconography, early Christian art, and the expressive power of color and form. In Women in the Countryside, we see these influences at play in a composition that blurs the boundary between figure and landscape, subject and symbol.

Composition: A Mystical Assembly of Forms

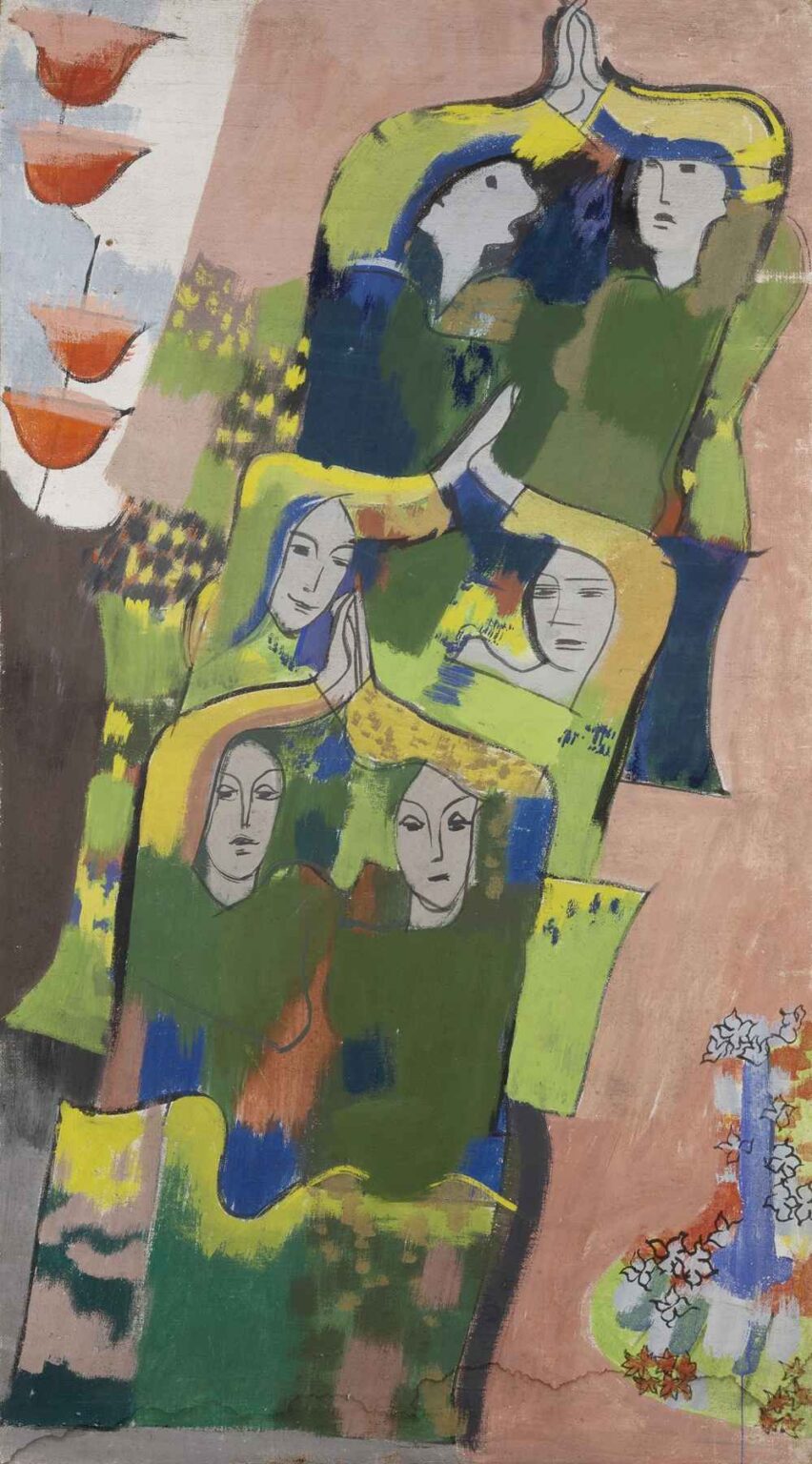

The painting features a vertical cascade of female figures, seemingly nested within one another, their forms partially obscured by stylized green garments that resemble both robes and foliage. The figures occupy the center and right half of the composition, arranged in a rhythmic, almost musical sequence. Their faces, pale and masklike, vary in expression from serene to solemn.

On the left, a vertical alignment of red, tulip-shaped forms emerges against a soft background, while in the bottom right, abstracted blossoms suggest a field of flowers or a floral altar. The background is filled with earthy pinks, taupes, and greys, lending the overall composition a grounded yet dreamlike feel.

Babberger forgoes traditional perspective in favor of a flattened space, where figures and forms flow into one another like a tapestry or a ritual procession. The composition evokes both vertical ascent and spiritual connection, hinting at iconography from Christian frescoes and medieval manuscripts.

Color Palette: Earth and Spirit

The dominant colors in Women in the Countryside are olive green, saffron yellow, ultramarine blue, and muted rose. These hues are neither purely naturalistic nor purely symbolic—they exist in a liminal space where both landscape and inner experience are expressed. The earthy greens evoke fields, foliage, and growth, while the reds and yellows add emotional heat and divine energy.

Babberger’s use of color is not descriptive but expressive. The faces of the women are rendered in pale greys and whites, creating a ghostly or timeless quality. These spectral complexions contrast with the vibrant garments, reinforcing the spiritual dimension of the figures.

His application of color—broad, dry brushstrokes layered loosely—is more concerned with emotional resonance than with precision. This technique heightens the sense of mystery and gives the painting its aura of contemplative stillness.

The Women: Allegory and Inner Landscape

The title Women in the Countryside invites a pastoral reading of the figures, but Babberger offers more than a simple scene of rural life. The women are stylized, almost hieratic. Their elongated necks, stylized hands, and almond-shaped eyes recall medieval icons or religious statuary. They are not individuals but archetypes—figures of meditation, fertility, or divine presence.

Several women are shown with hands in prayer or contemplative gesture, reinforcing the idea that this is a spiritual assembly rather than a literal one. The women may be interpreted as earth goddesses, muses, or personifications of nature’s cycles—spring, harvest, dormancy. Their forms are embedded within the very fields they occupy, blurring the line between body and land.

By portraying them as both human and elemental, Babberger elevates the rural woman to a position of sacred reverence. This is not a modernist critique of labor or class, but a symbolic affirmation of femininity’s spiritual role in the cycle of life and the ecology of place.

Symbolism: Sacred Geometry and Nature

The vertical composition of the women suggests a tree or vine—one that grows upward toward the heavens while remaining rooted in the earth. This may allude to the “Tree of Life,” a common motif in religious art and mysticism. The repetitive placement of red tulip-like shapes on the left could be interpreted as stylized lamps or chalices, perhaps symbolizing fertility, spirit, or the sacred feminine.

In the bottom right, the abstract floral arrangement further connects the painting to nature and ritual. It may represent an offering or altar, suggesting that the countryside is not just a geographic space but a temple—a space for communion with the divine.

The way Babberger interweaves the human figure with natural patterns and rhythms aligns with Symbolist traditions. His abstraction is not just visual but metaphysical, offering a vision of the countryside as an eternal, living structure animated by feminine presence.

Emotional Tone and Psychological Resonance

Despite the serenity of the composition, the painting carries an undercurrent of melancholy. The expressions of the women are mostly solemn; their eyes are heavy-lidded, their mouths closed in contemplation. There is no narrative action, only presence. This stillness, combined with the ambiguous setting, creates a mood of timeless meditation.

This emotional tone invites the viewer to reflect not only on the landscape but on interior states of being. The countryside is not simply a location—it is a metaphor for inner life: quiet, cyclical, nurturing, and occasionally mournful. The painting thus becomes a psychological landscape, where color and form mirror spiritual conditions.

Influence and Art Historical Context

August Babberger’s work occupies a unique place within German Expressionism. While other artists of the era—such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Emil Nolde—often depicted anxiety, urbanization, or existential rupture, Babberger pursued a more contemplative path. His influences include Symbolism, early Christian art, and decorative modernism.

Women in the Countryside can be viewed as a spiritual successor to works by Franz Marc, who sought the divine in animals and color, or Paula Modersohn-Becker, whose rural women were rendered with similar reverence. Yet Babberger’s style remains distinct: less focused on realism or emotional drama, and more aligned with mystical abstraction.

The mural-like flatness and use of repeated forms also recall the Art Nouveau aesthetics of Gustav Klimt, particularly his golden iconographic works. Babberger, however, strips away the opulence and replaces it with quiet earthiness, re-rooting mysticism in the soil.

Post-War Reflection and Sacred Space

Painted in the wake of World War I and amid rising tensions in Europe, Women in the Countryside can also be seen as a refuge from violence and modernity. In a world increasingly defined by mechanization and conflict, Babberger returns to the archetypes of nature, femininity, and contemplation.

Rather than depict suffering directly, he offers a sanctuary—a space where time stands still and the sacred can still be found in simple, rural forms. This aligns with the post-war impulse among many German artists to seek solace in spirituality, nature, or myth after the disillusionment of war.

Conclusion: A Modern Icon of Earth and Spirit

Women in the Countryside by August Babberger is a quiet but powerful painting. It does not shout; it sings softly—a hymn to the feminine, the pastoral, and the sacred rhythms of nature. Its abstraction is not alienating, but intimate. Its symbolism is not arcane, but resonant.

Babberger’s achievement lies in his ability to fuse the spiritual and the modern, to craft an iconography for the 20th century that honors both tradition and innovation. This painting invites not just viewing but meditation. It asks us to pause, reflect, and recognize the sacredness in stillness, community, and landscape.

For contemporary audiences, Women in the Countryside remains a moving visual poem—one that reminds us of the deep connections between art, earth, and inner life.