Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

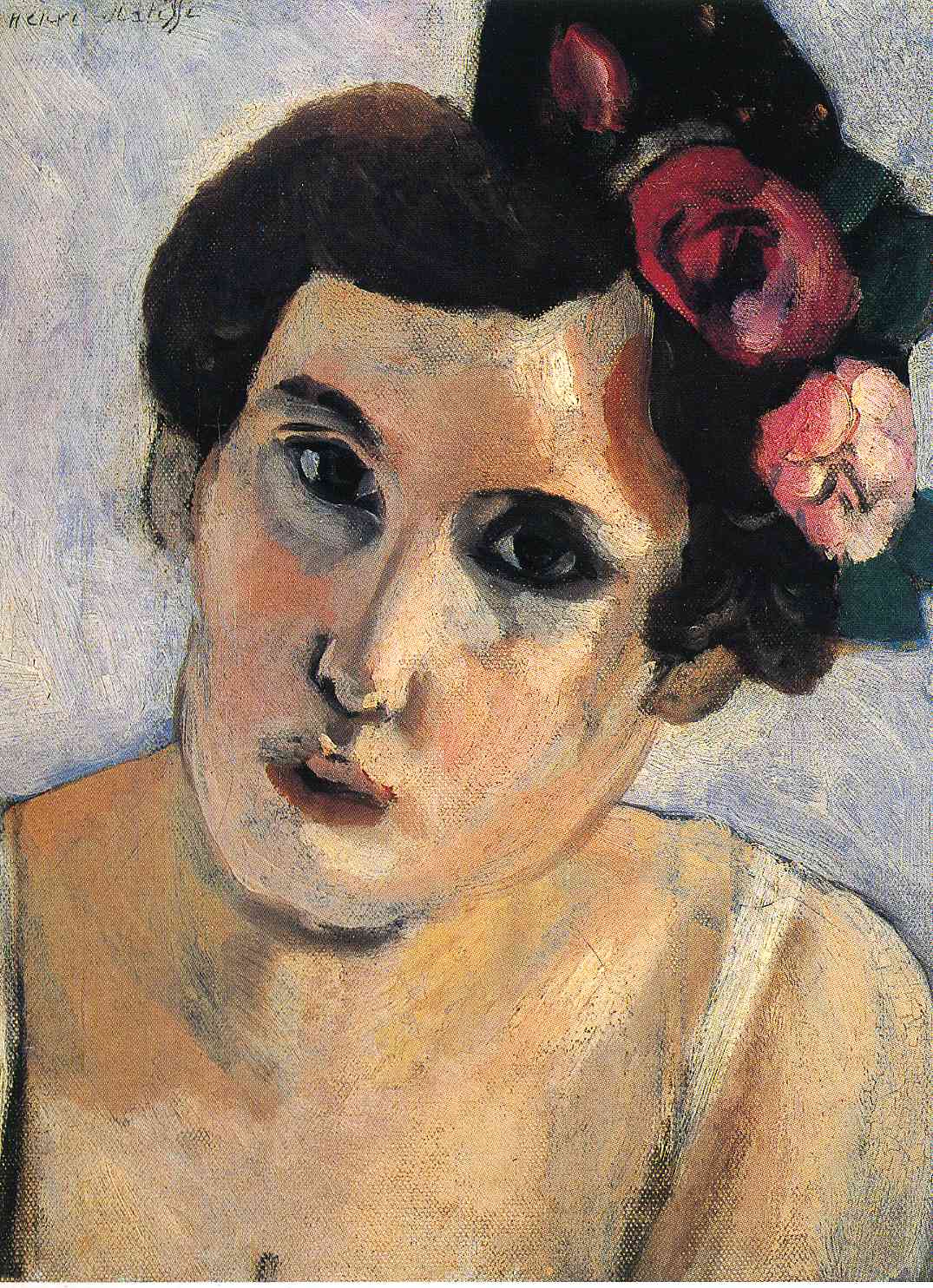

Henri Matisse’s “Woman’s Head, Flowers in Her Hair” (1919) is a compact manifesto for the artist’s postwar turn in Nice. Composed as an extreme close-up, the portrait abandons props and architectural scaffolding to concentrate on the head as a radiant field of color and touch. The sitter tilts toward us; her dark, lucid eyes meet the viewer with a mixture of candor and distance, while a cluster of roses tucked into her hair becomes a chromatic counterpoint to flesh. The background is a cool, breathed-on violet that keeps the face suspended in air. Nothing here is descriptive excess; every stroke is placed to register light, temperature, and the quiet drama of looking.

The Nice Climate and a New Clarity

Painted in the first years after World War I, the picture belongs to Matisse’s celebrated Nice period, when he sought a language of calm after a decade of restless invention. In this southern light he replaced high Fauvist contrasts with a more measured palette and a steadier, domestic intimacy. Windows, shutters, and patterned screens recur in the period as tools to measure radiance. In this portrait he sets almost all of that aside. The vision is distilled to face, flowers, and atmosphere, a choice that declares confidence in the sufficiency of color and “arabesque”—his term for the living line—to carry emotion without anecdote.

First Impressions: Nearness as Drama

The work’s magnetism begins with scale. The head is cropped at the chin and shoulders, and one strap of a garment barely enters the frame. Such nearness converts the canvas into a negotiation between viewer and sitter. The absence of distractions increases the ethical pressure of the gaze: we are asked to meet another person’s steadiness with our own. Matisse’s decision to tilt the head slightly left enriches that encounter, creating an oblique plane across which light can travel. The roses on the right balance the darker hair mass on the left so that the composition doesn’t topple; equilibrium reads as poise rather than rigidity.

Color Architecture and Temperature

The palette is deliberately limited. Flesh is built from ranges of warm ochre, pale rose, and cream that shift almost imperceptibly into cooler notes along the jaw and temple. The roses bring deep crimson and a soft shell pink, hues that rhyme with mouth and cheek while standing against the surrounding greens and blacks of hair and leaves. The background is a lavender-gray containing enough blue to feel airy and enough red to harmonize with the flowers. Black appears sparingly—pupils, hair shadows, the line under the mouth—and therefore carries structural weight. Because each color family repeats across different zones, harmony replaces description: the red of a petal activates the lip; a cool gray near the eye returns in the halftones of neck and strap.

The Living Contour

Matisse treats drawing not as an outline to be filled but as a breathing edge. Around the cheek and chin, the contour swells and thins, recording the pressure of the brush as an event in time. Over the nose he refuses fussy modeling; a few gently angled strokes establish bridge and tip, allowing color temperature to do the turning. The lips are a sequence of two or three related notes, the lower lip warmed and the corners darkened, enough to land the mouth without trapping it in detail. He gives the eyes a precise upper lid and floating, glossy pupils; the slight asymmetry gives life rather than error. The result is a face that feels constructed and alive at once.

Brushwork and Surface

The surface remains candid. In the background the brush moves broadly, letting the weave of the canvas breathe through a thin violet film; the air of the room seems to circulate behind the head. In the flesh passages, paint is richer but still open. Matisse often scumbles pale pigment over a darker under-tone so that a granular vibration replaces academic blending. The roses are the most impastoed passage—a few loaded touches, dragged and lifted, persuade the eye of velvety petals without counting them. In every register, facture is visible and rhythmically varied, the painterly equivalent of a held breath.

Flowers as Counterpoint

The roses are more than adornment. They perform several formal tasks. Chromatically, they deliver the portrait’s warmest reds, tightening the interval between mouth and cheek while energizing the cool ground. Spatially, they push the head toward the center by adding weight to the right margin. Symbolically, they carry a long tradition of floral femininity, but Matisse empties that tradition of sentimentality by abbreviating forms and refusing anecdote; the flowers are notes in a chord, not a story. Their leaves, shifted toward deep green, keep the bouquet from dissolving into a mere red cloud and echo dark passages in hair and eye.

Light Without Theatrics

Light here is Mediterranean, but moderated. Rather than cast a single directional beam, Matisse sets up a general illumination that turns forms by temperature. Coolness settles under the eyes and along the jaw; warmth concentrates on the forehead and cheek where blood comes close to the surface. The effect is both sculptural and tender. Highlights are withheld except for the slightest glistens in each pupil and a breath along the ridge of the nose. Because the ground remains cool and pale, the face reads as lit from within rather than spotlighted from without.

The Psychology of Restraint

The sitter’s expression is at once direct and undelivered. There is no narrative clue, no accessory to hint at profession or circumstance. Matisse prefers a psychology of restraint, where presence is achieved not by descriptive minutiae but by the firmness of placement and the cadence of looking. The slight parting of the lips, the thoughtful tilt, and the dark, steady eyes suggest an interior life precisely because they are not over-insisted upon. This quiet invites projection; the portrait meets us halfway and leaves the rest to attention and time.

Cropping and the Modern Head

The modernity of the picture rests partly on its cropping. Whereas nineteenth-century portraiture often presented torso and hands as rhetorical instruments, Matisse sets the head loose from body and setting. The strap at the right border is enough to indicate a living body below; the rest belongs to pictorial necessity. Such cropping implicates photography, yet the result is decisively painterly: edge decisions advertise themselves as choices, and the paint’s granularity keeps the face from becoming a glossy icon. The head becomes a world without needing to be a bust.

Comparisons Across the 1919 Portraits

Looked at alongside Matisse’s other portraits of 1919—“The White Feather,” “Portrait of Yvonne,” “The Green Sash”—this canvas feels both intimate and experimental. Those works often include hats, necklaces, patterned upholstery or reflective mirrors that tune the color chord. Here, the head alone must do the work, assisted only by a floral accent. The experiment succeeds because his Nice approach is already securely internalized: a stable ground, a limited palette tuned by temperature, and an absolute trust in the eloquence of contour. It is a study in sufficiency.

Likely Palette and Practical Craft

The harmony likely proceeds from a compact set of pigments. Lead white builds the body of light in background and flesh. Yellow ochre and raw sienna inflect the warm skin notes; a touch of vermilion or cadmium red gives the lips and roses their warmth, tempered by alizarin or carmine for the deeper crimson. Ultramarine and cobalt supply the cools of ground and shadows, sometimes greened slightly to meet the leaf tones. Viridian contributes to foliage; ivory black clarifies pupils, hair accents, and a few defining contours. The paint is mostly opaque with controlled translucency where flesh turns, the old master’s play of scumble and reserve carried into a modern register.

Rhythm and the Eye’s Path

The portrait asks for a slow loop of looking. Many viewers begin at the left eye, cross the bridge of the nose to the right eye, drop to the mouth, travel up the cheek to the cluster of roses, drift into the soft violet field, and return to the eyes again. Each circuit strengthens relationships: lip red to rose red, hair black to pupil black, cool ground to cool halftone. The rhythm is gentle, tactical, repeatable. Nothing arrests the loop with a sharp anecdote; instead the painting sustains a continuous present in which the head keeps arriving.

The Ethics of Economy

Economy is central to the work’s authority. Matisse refuses to labor the face into likeness by accumulation. He works by placing a few large relations correctly and letting the mind complete what the eye implies. This ethic dignifies the viewer’s participation; it also allows the painting’s freshness to endure, because each return finds the decisions still legible rather than buried under finish. In the years following global trauma, such clarity reads as a choice for steadiness—an art that does not dramatize but consoles and awakens perception.

How to Look, Practically

Approach close enough to feel the canvas’s grain. Notice the soft violet ground scumbled thinly so that the texture flickers through. Step to the roses and attend to how few strokes are asked to stand for petal and leaf. Back away until the features cohere and the head seems to breathe. Let your gaze pass from the deep pupils to the warm cheek and back; stay long enough to feel the heat of the reds subside into the cool of the ground. The portrait repays this patient oscillation with a durable sense of presence.

Meaning Without Narrative

What does the painting mean beyond its exquisite craft? It proposes that presence can be composed from pure relationships—color intervals, edge pressures, fields of air—without recourse to anecdote. The human face, simplified and brought close, becomes a place where the viewer’s own attention is tested and quieted. The roses admit beauty frankly without resorting to symbol. Seen this way, the canvas is both a likeness and a demonstration: a person appears, and painting’s unique means for making a person appear are put on open display.

Conclusion

“Woman’s Head, Flowers in Her Hair” condenses the virtues of Matisse’s Nice period into a single, concentrated image. With a limited palette, a breathing contour, and a background of clarified air, he gives us not an embellished persona but an encounter—face to face, color to color, time to time. The roses do their work as accents, the eyes hold their dark light, and the whole remains transparent about how it was made. It is a small painting that feels large, because it asks little and gives much: steadiness, nearness, and the felt intelligence of paint.