Image source: wikiart.org

Overview of “Woman with Dark Hair” (1918)

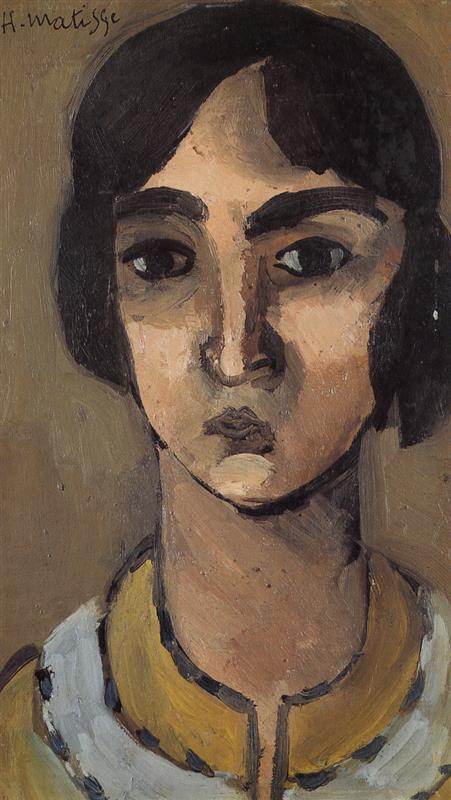

Henri Matisse’s “Woman with Dark Hair” compresses the intensity of a full-length portrait into a head-and-shoulders study that reads like a declaration. The model fills the narrow vertical panel; her gaze meets ours without theatricality; the background is a plain, warm ochre that isolates the head like a reliquary. Everything is simplified to essentials—broad planes, decisive contours, a restricted palette—yet the picture vibrates with presence. Painted in 1918, at the dawn of Matisse’s Nice period, it shows the artist refining a language of calm clarity after a decade of experiment. The Fauvist blaze has cooled, but the courage of placement remains. With a few harmonized tones and the authority of black, Matisse builds a face that is as much architecture as likeness.

Historical Moment and Artistic Pivot

The date matters. Europe was emerging from the First World War, and Matisse was turning from the high-strung structural canvases of the mid-1910s toward the tempered light and equilibrium he would cultivate in Nice. In this painting, he keeps the directness of his earlier drawing while tuning color to a moderate key. Rather than chase description, he composes relationships: warm flesh against ochre ground, black against wet brown, a yellow-gold collar that anchors the lower edge. The portrait belongs to a cluster of early Nice works in which Matisse tests how much character can be carried by a few tones and the handwriting of the brush.

Composition: A Face as Architecture

The head occupies nearly the entire height of the panel. That compression changes how we read the face: brow, nose, and mouth become structural beams; the cheeks are planes; hair is a framing device. The central axis of the nose is strongly drawn and slightly widened, declaring the face’s frontality. The eyes sit on a broad horizontal, heavy-lidded and asymmetrical enough to feel human rather than diagrammatic. The mouth is compact, set by a few angular strokes that catch volume without softening the overall resolve. Matisse balances the head with the firm geometry of the neckline, the keyhole opening of the collar, and the truncated shoulders. The result is a portrait that feels built—constructed from interlocking shapes—rather than modeled in the academic sense.

Palette: Tempered Warmth and Living Neutrals

Color is reduced but precise. The background is a warm ochre broken by slight modulations that leave the surface breathing. Flesh gathers from muted rose, ochre, and brown-gray, and is stabilized by small cool notes around the eyes and along the jaw where shadow cools the skin. Hair is not a flat mass of black; it is a field of dark browns with black accents that take the light at their ridges. The collar is a honeyed yellow edged with gray and punctuated by small dark marks; it supplies the painting’s warmest saturation and keeps the composition from toppling forward. Because saturation is moderated across the board, temperature shifts carry the sensation of light. The face glows because warm cheeks sit next to cooler shadows and because the ochre background gently amplifies the warmth of the skin.

Black as a Positive Color

Matisse is one of the twentieth century’s masters of black used as color. In “Woman with Dark Hair,” black and near-black strokes do the heavy structural lifting. They lay down the eyebrow arcs, outline the nasal bridge, weight the inner contours of the hair, and punctuate the mouth’s corners. Where black abuts skin, it intensifies the neighboring tones; where it touches the ochre ground, it gleams with a slight halo as the wet brush dragged across layers. The line thickens and thins with the turning of form; it is not an outline pasted on top but a living edge that carries the portrait’s rhythm.

Brushwork and the Visibility of Making

The paint handling is frank. Strokes interlock rather than dissolve; you can track decisions: a cheek plane set by a broad drag of the brush; a quick, angular pass to fix the mouth’s shadow; a darker sweep reinforcing the hairline. The background is laid in with long, slightly varied strokes that leave a grain, preventing the field from going dead. Matisse avoids cosmetic smoothing. He prefers surfaces where each zone has its own tempo—faster around the features, slower in the ground and collar—so that the image remains alive at close range and calm at a distance.

The Face as a System of Planes

Instead of pushing volume with photographic shading, Matisse turns the face through planes. The forehead tilts back with a cooler, gray-brown note; the cheekbones round forward with warm ochre and rose; the nose is built as a broad wedge with strong flank shadows; the chin receives a darker under-plane that sets the head on the neck. Everywhere the transitions are abbreviated. A narrow band of cooler tone is enough to send a plane away; a warmer stroke returns it. This planar thinking gives the portrait its clarity and explains why it reads with such authority even as particulars are left out.

Eyes, Mouth, and the Register of Attention

The eyes carry weight without resorting to detail. Upper lids are heavy, with dark arcs that suggest thick lashes and the shadow of brow. Pupils are small but set with enough value contrast to establish a focused gaze. The irises are not fully resolved; they are implied by the placement of lights and darks, a strategy that keeps the eyes vivid without sliding into a photographic trap. The mouth is compact, slightly pursed, and off-center by a hair—enough to humanize the masklike symmetry of the frontal head. Together these choices create an expression that is reserved, alert, and introspective rather than theatrical.

Hair and the Iconography of Darkness

The “dark hair” of the title is not mere description; it frames the face like an icon’s nimbus turned nocturnal. Thick passes of black-brown define lobes around the cheeks, while lighter brown strokes inside those masses keep the head from reading like a helmet. A short lock turns inward near the right temple, breaking symmetry and injecting motion. The hair’s darkness allows the mid-value flesh to sit between two tonal poles—black hair and ochre ground—so the face becomes the mediating middle, the “speaking” register of the painting.

Background as Stage and Climate

The unadorned ochre background is an active participant. Its warmth collects behind the head and collar, intensifying flesh and yellow. Because it is a single, breathable field, it grants the portrait a sense of climate—an indoor light, soft and steady—and keeps attention on structure rather than on setting. The background’s slight brush variations produce a hum that prevents monotony while resisting the distraction of pattern or anecdote. As in many early Nice works, Matisse substitutes climate for narrative, making mood arise from color relations rather than props.

Dialogues with Tradition, From Icons to Ingres

The portrait speaks quietly with several traditions. The frontal head, plain ground, and strong contour recall the hieratic stillness of Byzantine icons and early Renaissance panels. But the planar construction and edited features echo Ingres filtered through modernism: contour as armature, interior modeling minimized, an ideal of clarity. There is also a whisper of Japanese print sensibility in the bold, flattened shapes and the calligraphic blacks. The result is neither eclectic nor derivative. Matisse absorbs historical devices and reassigns them to his own priority: a face made fresh through the exact placement of a few relations.

Comparisons within Matisse’s 1916–1919 Heads

Placed beside the series of heads and half-figures he painted around 1916–1919, this portrait reads as a distilled statement. The simplified, dark-browed oval recalls the portraits often associated with his model Laurette, while the reduced palette anticipates the calm of the Nice interiors. Compared with the aggressively carved features of some 1916 canvases, this face is softer and more breathable; compared with the pattern-saturated odalisques to come, it is austere. It sits at the crossroads of severity and sensuousness, a balance that makes it feel both intimate and monumental.

Scale, Format, and the Experience of Looking

The panel’s narrow vertical format forces the viewer into a one-to-one encounter. There is no digression into hands or clothing; no room to wander into background. This compression focuses attention on relations: how the eyebrow arcs echo the collar’s curves; how the keyhole opening mirrors the mouth’s central shadow; how the central axis is asserted and then gently contradicted by the slight tilt of the head. The portrait teaches a kind of close looking that fits Matisse’s ethos of sufficiency—seeing more by insisting on less.

Edges, Seams, and the Craft of Meeting

Edges in this painting are expressive devices. Hair meets skin with a firm, dark seam; skin meets background with a softer join that sometimes produces a faint halo, a by-product of wet-over-dry painting that Matisse leaves visible as evidence. The collar’s yellow meets gray edging with a crisp boundary that declares fabric; the neckline meets the chest with a broad, shaded V that sets the head in place. These tailored seams hold the simplified shapes together and let the portrait breathe.

The Ethics of Calm

Matisse’s stated wish for pictures that offer “balance, purity, and serenity” has special force in a head like this. The calm is not anesthetic; it is exactitude. Each stroke has a job; nothing is redundant. Because the portrait refuses drama, it invites attention. Because it suppresses anecdote, it magnifies relation. The viewer comes away with a sense of steadiness that is deeply modern: feeling carried by clarity.

How to Look: A Guided Circuit

Begin at the dark arcs of the eyebrows, where black registers most strongly against flesh. Follow the bridge of the nose down to the compact mouth; notice the quick, angled strokes that set the upper lip’s shadow and the small, light patch that catches the lower lip’s volume. Slide outward to the collar’s yellow and feel how its warmth rises against the cool gray edging. Climb the right cheek, reading the shift from warm to cool as the plane turns, then enter the hair’s interior where brown strokes move like currents beneath black. Step back to the ochre field and register how it holds the head like a shallow stage. Repeat the loop; the portrait’s rhythm becomes bodily—breath up through the nose, out across the mouth, a quiet cycle.

Material Evidence and the Courage to Stop

Pentimenti—traces of revision—give the painting its earned authority. A softened echo of the earlier hairline glows under the final contour; a cooler veil crosses the cheek where Matisse adjusted the plane; the collar’s edge shows where yellow pushed over gray to clean the shape. He does not polish these seams away. He stops when the relations are right, not when surfaces are cosmetically smoothed. That decision is why the portrait feels present rather than rehearsed.

Why It Still Feels Contemporary

A century on, “Woman with Dark Hair” looks strikingly current. Its big, legible shapes read at a glance; its palette feels sophisticated; its visible process satisfies a modern appetite for honesty; its shallow space matches photographic and graphic sensibilities. Most contemporary of all is its premise that a small number of tuned relations—ochre ground, dark hair, planar face, living black—can carry the weight of a person’s presence. In an image-saturated age, that economy reads as generosity.

Conclusion: A Face Built from Essentials

“Woman with Dark Hair” is a masterclass in reduction without loss. With a narrow format, a handful of tones, and the confident calligraphy of black, Matisse conjures a face that is stable, alert, and humane. The painting stands at the threshold of the Nice period, carrying forward the structural resolve of earlier years and pointing toward the calm atmospheres to come. It is a portrait you don’t get over quickly, because it shows how much of a person can be said with so little—how contour, plane, and temperature, placed exactly, can become character.