Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

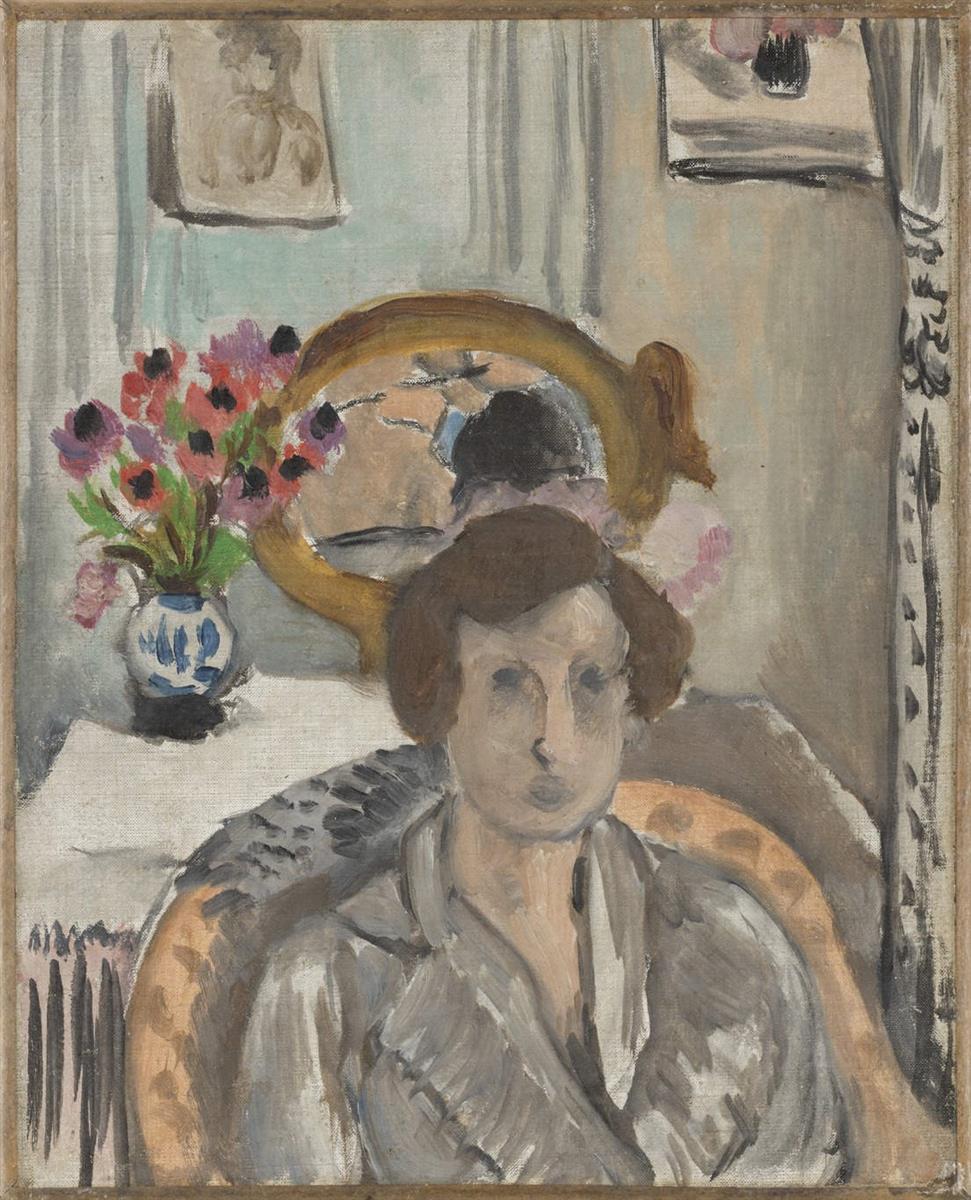

Henri Matisse’s “Woman with Anemones” (1919) gathers the essential grammar of his early Nice period into a compact, intimate room: a seated woman in a softly colored robe, an oval gilt mirror, pale curtains, and a bright vase of anemones arranged on a small table behind her. The composition is restrained in palette yet rich in relations. Warm grays, beiges, and silvery blues shape the figure and her chair; the bouquet supplies crisp notes of red, violet, and black; the mirror captures a fragmentary reflection that doubles the scene while keeping it private. Everything is close to the surface. The space is shallow, the objects ordinary, the light even and humane. Out of these quiet means, Matisse builds an image of presence that feels both modern and timeless.

The Moment in Matisse’s Career

The year 1919 finds Matisse working in Nice just after the First World War, turning from prewar volatility toward rooms and balconies bathed in Mediterranean light. This shift is not retreat but a different kind of ambition: to rebuild harmony with lucid color, designed space, and subjects that honor daily life. “Woman with Anemones” belongs squarely to this program. It forgoes bravura effects for a poised balance of portrait, still life, and interior. In the process it shows how Matisse could make a small canvas carry the weight of his larger aesthetic convictions: color as structure, pattern as rhythm, and clarity as an ethical stance.

First Impressions and the Scene Described

A woman sits forward in an upholstered chair, her torso framed by a gently rounded back. Her robe reads as soft, brushed gray with cool silvery highlights; the neckline opens modestly; the sleeves fall in simple planes. Behind her, an oval, gold-framed mirror catches a sliver of her head and a glint of the bouquet. To the left, a vase painted in blue on white holds anemones—pink and crimson petals punctuated by dark eyes. Pale curtains hang like vertical bands, barely stirred. On the wall are two small works, one a monochrome figure study, the other a square canvas with a dark flower form. Nothing is ostentatious; everything contributes to an atmosphere of thoughtful quiet.

Composition as a System of Ovals and Bands

The composition is ordered by two governing shapes. First is the family of ovals: the sitter’s head, the rounded back of the chair, the full ellipse of the mirror, and the blossoms that collect in soft, circular heads. Second is the family of bands: the vertical curtains, the edge of the table and cloth, and the column of decorative marks along the right margin. Ovals provide human warmth and enclosure; bands supply architectural poise. The sitter occupies the lower center, while the mirror and bouquet occupy the upper left, creating a diagonal conversation that keeps the painting dynamically balanced without disturbing its calm.

Palette and the Authority of Restraint

The color key is characteristically Nice: a civilization of grays and creams gently warmed by flesh tones, with strong chromatic accents carefully rationed. The robe and chair live in silvery neutrals; the wall is a pale, slightly greened gray; the curtains add milky verticals; the mirror’s frame introduces a honeyed gold that glows without shouting. Then come the anemones: wet reds, pinks, and violets punctured by black centers. Those few saturated notes do all the heavy lifting of color contrast, and because the rest of the palette is disciplined, the bouquet can ring out like a bell without breaking the room’s harmony. The lesson is Matissean: not more color, but truer relations.

Light and Atmosphere

Light arrives evenly, as if filtered through high windows. It does not cast harsh shadows; it rests on surfaces and clarifies them. The robe’s folds are turned by temperature shifts rather than by dramatic value jumps; the chair’s surround glows softly; the mirror holds a low, dawnlike gleam that turns its gold frame to waxy light. Across the tablecloth and wall, the brush thins, letting the canvas weave breathe so the room feels airy. The atmosphere is a climate made for looking: bright enough to distinguish planes, soft enough to keep color alive.

The Mirror’s Double Work

The oval mirror is not a decorative flourish; it is a structural and psychological agent. Structurally, it resolves a frequent portrait problem—the emptiness that can accrue behind a sitter’s head—by providing an animated, circular field that echoes the face while remaining distinct. Psychologically, it creates a secondary, indirect portrait: a faint, broken reflection of head and bouquet. Because the reflection is partial, the mirror protects the sitter’s privacy even as it multiplies her presence. It also directs the eye toward the anemones, binding figure and still life into a single circuit.

The Bouquet as Color Engine

The anemones are painted with rapid, juicy touches that state petal and eye with minimal fuss. They sit in a small ceramic vase banded with blue arabesques—another echo of the Nice vocabulary, where pottery, screens, and printed fabrics carry pattern into the room. The flowers’ task is to deliver decisive color without scattering attention. Matisse places them against pale cloth and within reach of the mirror’s gold so they read immediately. Their dark centers act like commas that punctuate the sentence of the painting, setting a rhythm that recurs in the sitter’s eyes and hair.

Drawing and the Living Contour

Matisse’s contour is present but never pedantic. The profile of the shoulder, the curve along the chair, the edge where robe meets neck—all are marked by a supple, variable line that tightens at joints and relaxes across soft fabric. In the face he uses a few succinct strokes to place brow, nose, and mouth; the eyes are washed in and then steadied with smaller darks. This economy of drawing preserves the freshness of the first look. The sitter’s likeness is not built from detail but from the calibrated relation of shapes.

Brushwork and Material Presence

The paint lies thin in the wall and curtain, richer in the bouquet and mirror, and somewhere in between across the robe. This graded handling lets materials carry their own truth: cloth feels soft because the paint is scumbled; petals feel moist because the brush leaves rounded ridges; gilt reads as luminous because it gathers thicker, warmer pigment along the rim. The surface never forgets it is paint—and that candor, rather than any attempt at illusion, gives the room its tactile life.

Space: Shallow, Breathable, Modern

Depth is held to a few degrees. Overlap—chair in front of table, bouquet in front of mirror—provides cues, but perspective is suppressed in favor of planar relations. The result is a modern, breathable shallowness. The sitter feels close not because she advances into deep space but because the surface comes forward to meet her. The picture is less a window than a screen on which color and shape compose their relations. This is the Nice period’s signature spatial compromise: hospitable without illusionistic excess.

The Ethics of Attention

Matisse’s interiors are experiments in care—care for objects, for the light that falls on them, and for the human presence among them. “Woman with Anemones” exemplifies this ethic. The tablecloth is not fussed over; it is granted enough strokes to sit in the room. The small drawings on the wall are not miniatures; they are suggestions, respectful of the larger harmony. The sitter is not dramatized; she is attended to with quiet steadiness. The painting asks the viewer to practice the same attention, to meet the room at its unhurried pace.

Portrait and Still Life in Dialogue

The canvas joins two genres without subordinating either. The sitter’s head and shoulders give the picture weight, while the bouquet provides color and tempo. The mirror mediates, letting still life and portrait rhyme: circular head to circular blooms, dark hair to black flower centers, soft cheeks to soft petals. By integrating these elements into a single design, Matisse prevents the painting from becoming a portrait with props or a still life with a stray figure. It is a unified interior where person and objects belong to the same weather.

Pattern as Quiet Pulse

Compared with Matisse’s riotous earlier patterns, the rhythms here are muted but persistent. The blue ornament on the vase, the scalloped darks along the right curtain, and the small marks at the chair’s upholstery form a low pulse that keeps the large gray planes from becoming inert. Pattern is structural support, not spectacle. Its restraint allows the blossom colors and the mirror’s gold to count for more.

The Psychology of Inwardness

The sitter’s expression is deliberately spare. The mouth is closed; the eyes are softly set; the gaze is inward or downward. The posture reads as present but unposed. This privacy is amplified by the mirror’s fragmentary reflection and the curtain’s framing folds. The painting’s feeling is not melancholy; it is inward composure. Matisse invites us not to decode a particular narrative but to inhabit a mood of calm concentration.

Comparisons within 1919

Seen beside other 1919 paintings—the balcony scenes with pink umbrellas, the nudes on coral couches—this canvas is grayer, more intimate, and more condensed. Where those works expand into outside air or soft upholstery, this one focuses on the conversational triangle of sitter, bouquet, and mirror. Yet the underlying methods are identical: shallow space, clear planes, a decisive accent color, and visible evidence of making. The difference is one of timbre rather than theme; “Woman with Anemones” plays the Nice chord in a lower, more interior key.

A Path for the Eye

The painting offers a natural circuit. The eye begins at the sitter’s face, descends the robe’s V to the chair’s curve, crosses to the left where the bouquet flares, rises through blossoms into the mirror’s gold rim, pauses at the fractured reflection, slides back down the curtain’s pale band, and returns to the face. Each lap reveals small echoes: a pink petal answering the cheek’s warmth, the vase’s blue repeating in quiet notes around the room, the mirror’s oval echoing the head and chair. The circuit is not a tour of details but a rehearsal of the painting’s structural music.

Dialogue with Tradition

Matisse is conversant with centuries of portraiture staged with mirrors and flowers—from vanitas still lifes to domestic interiors by Manet and Morisot—but he translates that heritage into his own grammar. He declines deep recession and polished likeness in favor of a living surface; he refuses symbolism in favor of felt relations. The bouquet is not allegory; it is color and rhythm. The mirror does not tell a moral; it builds space and doubles presence. Tradition becomes a framework to be simplified and made modern.

Material Truth and the Fact of the Canvas

Throughout, Matisse lets the canvas show. The weave is visible in pale regions; the paint thins at edges where the brush lifts; small revisions peek through around the chair and face. These traces keep the image honest. The viewer senses the sequence of decisions—the placement of the bouquet, the adjustment of the mirror oval, the final dark accents that steady the features. Such material truth is essential to the painting’s intimacy. We are not confronted with a sealed illusion; we are invited into the act of making.

Meaning for Today

“Woman with Anemones” remains resonant because it enacts a discipline of looking that counters haste. It proposes that a person seated in a chair, a handful of flowers on a table, and a moderate light are sufficient grounds for beauty when arranged with care. In a culture of visual noise, the painting models a room tone in which attention can thrive. Its values—clarity, relation, restraint—are not historical curiosities but durable ways of seeing.

Conclusion

Matisse’s small interior achieves a generous largeness. A woman at ease, a vase of anemones, an oval mirror, and a few pale curtains become a field where color and contour do meaningful work. The restricted palette grants the bouquet authority; the shallow space keeps the surface alive; the mirror doubles presence while protecting privacy. Nothing is extraneous and nothing is neglected. In “Woman with Anemones,” Matisse shows how a modern picture can be at once decorative and profound, intimate and monumental, an everyday scene and a complete architecture of light.