Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

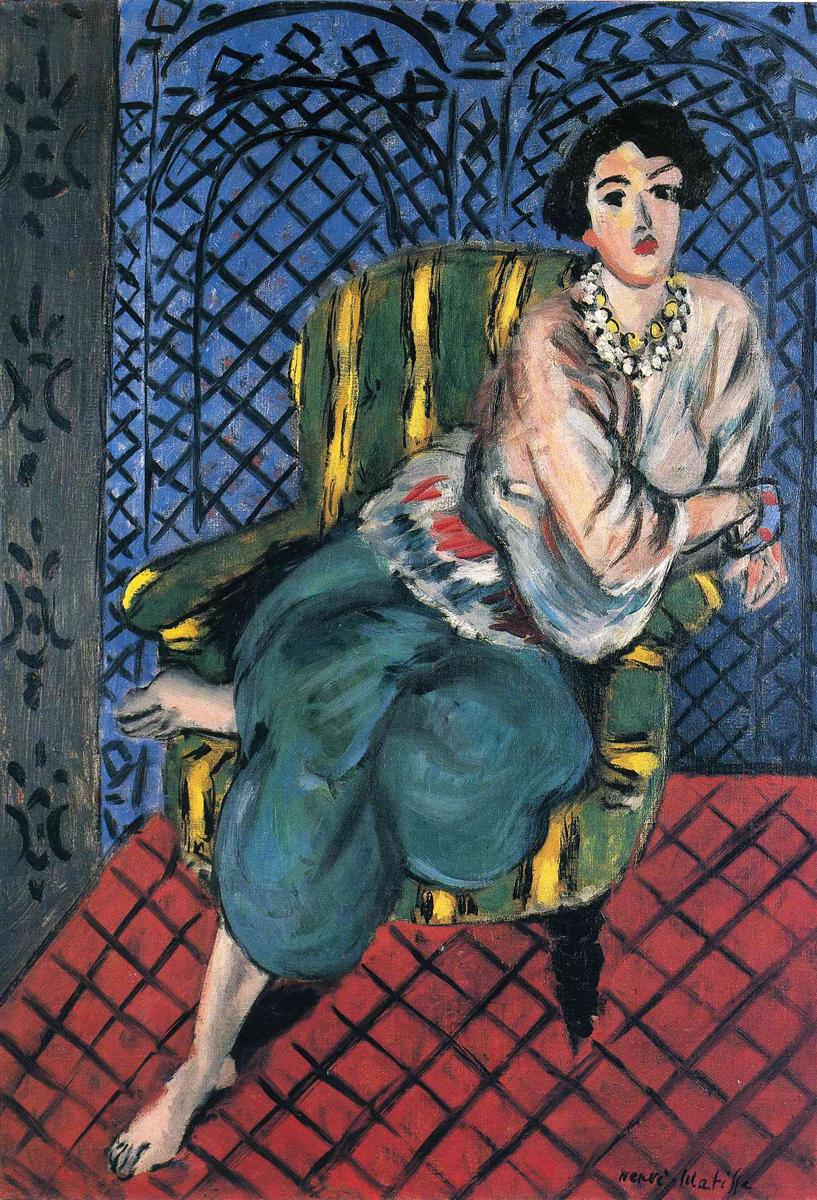

Henri Matisse’s “Woman Sitting in a Chair” (1926) compresses the language of his Nice period into a single, concentrated interior. A young woman folds herself into a low, striped armchair whose green upholstery and mustard bands glow against a cool blue lattice screen. A red tiled floor rises like a stage toward the picture plane, and the sitter’s bare feet press into that chromatic grid with frank, unposed weight. Jewelry flashes at the neckline; a pale blouse pools into pearly folds; loose turquoise trousers gather about the knees. The space is shallow, the patterns insistent, yet the mood is composed. Matisse’s interest is not anecdote but relation—how color behaves as architecture, how pattern sets tempo, and how a living contour can grant a figure calm authority amid decorative abundance.

The Nice Period And The Decorative Ideal

By 1926, Matisse had tuned his Nice-period method into a modern classicism. The Riviera’s filtered light allowed him to explore long, breathable harmonies of color rather than the shock chords of Fauvism. Interiors became theaters: portable screens, patterned textiles, a few pieces of furniture, and models who could sustain stillness without stiffness. The aim was not to mimic reality but to compose it, simplifying form while intensifying sensation. “Woman Sitting in a Chair” belongs to this ethic. The decorative is not an accessory; it is the logic by which figure and space are joined. The sitter is neither a character from a story nor a type from folklore; she is a poised presence, an axis around which the room’s intervals find their balance.

Composition As A Compact Stage

The composition is constructed as a compact stage, with three dominant planes pressed toward the viewer: a red floor patterned in dark diagonal lines, a green chair striped with mustard bands, and a blue screen whose lattice is hand-drawn in breathing strokes. The sitter’s body forms a gentle zigzag: right shoulder forward, arms folded, hip turned, knees bent, left foot tucked, right foot extended to the floor. This angled rhythm keeps the static act of sitting alive. The chair’s curved crest encloses the head like a halo of upholstery, and its legs grip the floor with small, emphatic shadows. A dark pilaster at the left edge serves as a visual hush, bracketing the orchestration of color on the right. Nothing is centered, yet everything is anchored. The diagonal thrust of the red tiles, the hemmed curves of the chair, and the nested arches of the screen create a set of counterforces that hold the figure in poised suspension.

Color As Architecture And Temperature

Color in this canvas does structural work. The cool blue of the screen builds the far wall, receding without dissolving thanks to the assertive lattice drawn across it. The chair’s green, thickened with yellow, acts as a warm middle ground that brings the sitter forward. The floor’s red injects heat into the foreground and prevents the blues and greens from relaxing into chill. Within this architectural triad, the figure carries a nuanced chord: the blouse is made of pearly whites that accept reflections from both chair and screen; the loose trousers settle into turquoise and sea green; the flesh is a small world of apricot, rose, and cool gray half-tones. Blacks are sparingly placed—eye, brow, bracelet, chair leg—to set the tonal range and to articulate edges without heaviness. The palette is compact but complete, and because each color borrows a little from its neighbors, the harmony breathes rather than locks.

Pattern And The Discipline Of Ornament

Pattern is never passive in Matisse. Here, it is the discipline that keeps the room in time. The blue screen’s hand-drawn lattice repeats at a medium tempo, establishing a steady meter that keeps the back plane animated. The red floor’s diamond network lays a slower bass line that lifts the foreground and guides the eye toward the chair’s feet. The chair itself adds a third rhythm: the mustard stripes climb the upholstery in vertical cadences that echo the screen while contradicting the floor’s diagonals. These independent beats interlock without congestion because Matisse allows the figure’s silhouette to cut across them cleanly. Ornament becomes grammar—an ordering system that clarifies relations.

The Figure’s Presence And Modern Poise

The sitter’s agency comes from poise rather than theatrics. Her face is simplified into readable planes: clean hairline, arched brows, the small dark of a mouth that holds the center quietly. The jewelry at the neck—white beads punctuated by a few yellow stones—serves as a cool crown that repeats notes from chair and screen. Arms cross without defensiveness; the body leans forward just enough to energize the chair’s embrace. Bare feet register the floor’s temperature and keep the body in the room rather than floating above it. The pose is modern in its directness, a collaboration between sitter and painter to preserve stillness large enough to host attention.

Drawing And The Authority Of Contour

Matisse’s contour does essential, understated work. Lines thicken where forms turn—at the shoulder and around the knees—and thin across lighter transitions. The chair’s limbs are drawn with firm arcs that avoid mechanical symmetry; their slight irregularity announces the hand and keeps furniture lively. The screen’s lattice is not a ruler’s grid but a calligraphic net, knots and crossings thickened by gesture. The facial features are set by a few unambiguous marks whose spacing creates the calm expression. These lines do not imprison color; they give it a living boundary. Because contour is so accurately weighted, modeling can be minimal, letting color carry volume.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

Light here is Riviera soft—diffuse, reflective, and friendly to color. Shadows in the blouse are cool violets and pale grays rather than black. The trousers accept olive shadows where they fold into themselves, and the chair’s stripes deepen where upholstery turns away from the light. On the floor, diagonal lines serve double duty as pattern and shadow, their darkness implying both surface and contact. Highlights are small and specific: the bead necklace shines with milky notes; the lip catches a compact red; a gentle gleam sits on the chair’s worn arms. The overall effect is a climate more than a spotlight, a steady illumination that lengthens looking.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

Although the canvas honors space—floor receding, screen behind, chair in front—its deeper intelligence lives on the surface. The red floor tilts toward us like a ramp, pulling the feet into view; the screen presses forward, insisting on flat decorative presence; the chair is a middle mass that bridges these planes. Overlaps supply just enough depth to persuade: the leg over the chair’s front edge, the arm before the torso, the chair foot casting shadow atop the tile. This productive flatness is the Nice-period solution to the old problem of interior space. It keeps perception on the surface where color, pattern, and contour can be read as thought.

The Chair As Pictorial Engine

The green striped chair is more than a prop; it is the painting’s engine. Its large mass binds the figure to the room, and its stripes repeat the rhythm of the screen while changing key. The upholstery’s greens swing warmer or cooler as they move around the form, translating the edges of light into color instead of into monochrome shade. The chair’s front legs step down like punctuation on the floor’s rhyme scheme; the upper ridge cradles the head and frames the face. Without this particular chair—its hue, its curved back, its banding—the design would lose its hinge.

Tactile Intelligence And Evidence Of Touch

Material differences are conveyed through touch rather than description. The blouse is painted as scumbled veils that allow undercolor to whisper; the trousers receive broader, creamier strokes that conjure the weight and nap of cloth; the screen’s lattice is drawn wet into wet, its lines slightly bled at crossings; the floor’s red is dragged so that canvas tooth participates, suggesting fired clay. Even the bead necklace is a string of thick, wet dots that catch light physically. This tactile intelligence grounds the decorative idea in paint’s reality and keeps the room palpable.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

Matisse’s favored analogy to music clarifies how this picture works. The screen’s lattice provides the steady meter, the floor’s diamonds are a slower ostinato, the chair’s stripes supply inner voices, and the figure sings the melody with a forward lean and crossed arms. The eye travels a composed path: from the right foot along the tiles to the chair leg, up the green band to the necklace, across the face to the folded arms, down the trousers to the tucked foot, then back to the floor for another loop. Each circuit reveals new harmonies—a yellow stone repeating a mustard stripe, a cool gray in the blouse aligning with a lattice cross, a soft red in the lips balancing the floor.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Woman Sitting in a Chair” speaks to Matisse’s seated odalisques of 1925–1926 but trades overt exoticism for civic poise. Its blue lattice and red floor converse directly with “Seated Odalisque,” while the green-striped furniture recalls the heraldic chairs that appear throughout the Nice interiors. Compared with the reclining pictures, the present work is more vertical and conversational, bringing the viewer to the sitter’s level. It also foreshadows the late cut-outs in the way figure and ground approach equality as flat shapes whose meeting edges do the expressive work.

Psychological Tone And Viewer Experience

The psychological register is collected and slightly alert. The forward lean implies attention; the crossed arms suggest self-possession rather than defense. The face reads as thoughtful without dramatics. The room’s saturation could have pressed into claustrophobia, but the cool blue field and the breathing contour keep the air generous. For the viewer, the experience is one of steady presence: not a narrative to decode, but a set of relations to inhabit. The longer one looks, the more calibrated the intervals feel—warm to cool, diagonal to vertical, curve to grid—until the image seems to hold its own weather.

Process, Pentimenti, And The Earned Calm

Traces of revision remain visible, and they deepen the calm rather than disturb it. A chair stripe is shifted and repainted to better align with the figure’s shoulder; a lattice crossing has been reinforced where it meets the head; a contour at the knee shows a softened earlier position. These pentimenti testify to a search for balance rather than to indecision. The serenity the painting projects is not a given; it is achieved, and the surface carries that history with candor.

Why The Painting Endures

The canvas endures because its pleasures are structural and renewable. Each encounter yields a fresh hinge: a mustard stripe recruiting a yellow bead, a blue cross in the lattice aligning with a cool fold in the blouse, a tile line finding echo in the crossed forearms, a pale highlight on the chair arm repeating as a glint on the lip. None of these correspondences exhausts the painting because they are symptoms of a deeper rightness: the intervals among parts are tuned to hold attention without strain. The picture remains hospitable, capable of being lived with, which was precisely Matisse’s ambition for painting.

Conclusion

“Woman Sitting in a Chair” is a concise manifesto of Matisse’s Nice-period art. Within a shallow interior, the artist arranges a blue screen, a red floor, a green-striped chair, and a poised sitter so that color becomes architecture, pattern becomes rhythm, contour becomes breath, and calm becomes an earned achievement. The decorative is not a veil laid over life; it is the method by which life is made coherent and generous. In the measured meeting of warm and cool, curve and grid, surface and depth, the painting finds a durable grace that continues to reward patient looking.