Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

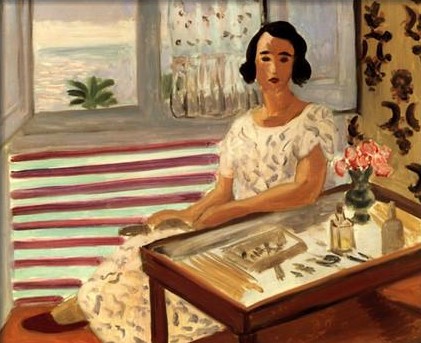

Henri Matisse’s “Woman Seated at Her Dressing Table” (1924) crystallizes the poise and clarity of his late Nice period. A young woman sits at a small mirrored table in front of an open window. Beyond the striped balcony the Mediterranean glints; inside, a vase of pink flowers, bottles, a comb, and scattered hairpins stage the quiet rituals of getting ready. The room is neither opulent nor spare. It is tuned—patterns, planes, and a handful of accents arranged to create the lucid calm Matisse sought in the 1920s. The painting is a compact treatise on how figure, décor, and view can harmonize without fuss, letting color do the expressive heavy lifting while line and shape maintain serene order.

Historical Context

By 1924 Matisse had worked in Nice for seven years, turning from Fauvist shock to a modern classicism of ambient light and decorative structure. He painted seated women, odalisques, readers, and musicians in shallow rooms filled with textiles, screens, flowers, and windows that open onto sea and sky. The dressing table motif appears frequently in these years because it merges still life and portraiture. It places the sitter in a world of intimate objects that carry both practical and pictorial roles: they punctuate the surface, set scale, and cue the rhythm of daily life. This canvas belongs to that family, yet it is distinctive for the frankness of its space and the crisp dialogue between interior and exterior.

Composition: A Triangle of Poise

The sitter forms a stable triangle. Her white patterned dress creates a luminous base that spreads across the chair and slips beneath the table edge; her torso rises calmly; the head, a compact oval with succinct features, completes the apex. The dressing table, set on a diagonal, counterbalances the figure’s verticality and guides the eye from the still life across the lap to the window. The top plane of the table is tilted—an old Matisse trick—to bring small objects firmly into the picture. The open casement frames a second composition: the red-and-cream stripes of the balcony, the turquoise slats beyond, and a sliver of sea with a palm. These stripes echo the table’s diagonal and provide a measured beat that paces the whole scene.

The Open Window and the Interior Duet

The wide window is a signature Matisse device. It fuses inside and outside in a single breath. Here it does even more: it makes the woman the hinge between the private tempo of dressing and the broader rhythm of the Mediterranean. The balcony stripes read like musical bars; the sea is a sustained, cool chord; a palm frond rises as a casual accent. The dressing table’s small cosmology—bottles, comb, hairpins—answers with domestic meter. As our gaze toggles from window to table, the painting’s subject becomes clear: attention itself, how the eye alternates between near and far, between the world and the self.

Color Climate and Temperature Control

Color provides both atmosphere and structure. The interior is warmed by honeyed browns of wood, the coral-red of the balcony awning, and the pink bouquet. Against this warmth, the woman’s white dress—picked out with small cool blue-gray marks—introduces quiet light. The sea and sky bring a fresh turquoise that resets the palette, ensuring the room never feels sealed. The face is modeled with pearly creams and faint violets, the lips a compact vermilion that anchors the visage. Matisse avoids harsh blacks; even the hair and eyes are softened by warm darks. Small accents tune the whole: the greenish stems in the vase, the gold of a bottle stopper, the cool glints on the tabletop glass. The result is equilibrium—no single color shouts; each lives by relation.

Pattern as Architecture

Matisse constructs space through patterns rather than linear perspective. The balcony’s bars and the window mullions establish a clear grid. The wallpaper at the right edge, with brown vegetal motifs, presses forward like a screen, balancing the open view. The dress’s soft sprig pattern echoes the wall while remaining lighter in key, so the figure stays luminous. The tabletop is a stage for miniature patterns: a book or mirror with crisp edges, a fan of hairpins scattered like small notes, and the elliptical mouth of the vase. These repetitions—bars, sprigs, scrolls, ellipses—give the composition its tempo and keep every zone participating in the same decorative order.

The Dressing Table Still Life

The still life is not accessory; it is the second protagonist. The glass-topped table reflects light in pale grays that tilt toward the sea’s color, creating a bridge between interior and exterior. The pink flowers offer a saturated warm pivot, echoing the balcony’s reds and the sitter’s lips. Bottles supply verticals that rhyme with the window posts; the comb and hairpins add linear accents that feel almost calligraphic. These small things carry weight: they focus the lower half of the canvas, prevent the white dress from dissolving into glare, and assert the domestic theme—the calm labor of self-presentation.

Light Without Theatrical Shadow

Nice-period illumination is ambient and benevolent. Here it settles everywhere: in the thin highlight along the table’s front edge, the milky sheen on the window curtain, the gentle brightening of the sitter’s forearm. Shadows are modest and transparent, never heavy. This avoids melodrama and leaves room for color to whisper the emotional tone. The painter’s goal is not to spotlight a narrative but to create a climate in which looking feels unhurried and exact.

Drawing and the Economy of Means

Matisse’s drawing is spare but decisive. The face is built from a handful of marks: arched brows, succinct lids, a short bridge of the nose, a compact mouth. The jaw is a soft plane, the hair a single dark mass edged by warm brown. Arms and hands are simplified into planes that do the structural job—one resting along the table, one across the lap. The dress is indicated by a few essential folds; its sprigs are brisk, repeated touches. Everywhere, contour breathes—tightening where necessary, relaxing elsewhere—so the figure reads as alive without over-description.

Space by Layers, Not Depth Tricks

Depth is created by overlap and temperature. Foreground: the table and its objects; middle: the sitter and chair; background: the window and the sliver of sea. The wallpaper panel pushes forward to keep the space shallow. This layered construction puts the viewer at conversational distance from the model and allows the objects to read clearly without perspective distortion. It also keeps the painting honest as a surface of colored shapes, a modern picture that acknowledges its own flatness while offering the pleasures of a view.

Psychology Through Poise

There is no theatrical narrative, no contrived emotion. The model looks outward with steady composure, neither inviting nor refusing. Her posture suggests a pause between actions—hands resting, articles laid out, book or mirror open. In Nice-period portraits, character is conveyed through equilibrium more than expression. The sitter’s dignity comes from her place in an ordered environment, suggesting a modern ethic: a life arranged for clarity and care.

Brushwork and Material Presence

The surface is enlivened by varied touch. The balcony bars are pulled in quick, elastic strokes that leave bits of ground showing; the sea and sky are scumbled into thin, cool planes; the flowers are built from loaded dabs that bloom at their edges; the bottles are drawn with swift, translucent loops that suggest glass without fuss. On the face and arms, paint thins to a pearly veil, letting underlayers glow through. These differences in pressure and speed keep the painting breathing and give it the tactile presence of a thing made by hand, in time.

Rhythm, Interval, and the Music of Looking

The picture’s rhythm is set by repeating forms. Bars of the balcony and window keep steady time; sprigs on dress and wall provide a softer pulse; the ellipses of vase mouth and bottle shoulders create rounded counterpoints; the pink blossoms and red balcony steps act as recurring refrains. Between these beats, Matisse leaves rests—broad planes of dress, sea, and tabletop—so the eye can linger. The tempo is unhurried, the way one moves while getting ready in a room with a view.

Dialogues and Comparisons

Compared with the odalisques and richly patterned interiors of the early 1920s, this painting is restrained. It retains the Nice vocabulary—ambient light, flattened space, decorative order—but channels it into a portrait anchored by the dressing table and the Mediterranean window. Compared with the musical scenes of 1923, it trades sound for ritual; compared with the “open window” pictures of earlier years, it brings the figure closer and grants greater dignity to everyday objects. Across these works, the constant is Matisse’s conviction that beauty emerges from tuned relations, not spectacle.

How to Look, Slowly

Start at the bouquet and feel its saturated pink anchor the lower right. Move along the glass tabletop, reading the small objects like notes in a bar of music. Let the diagonal lead you to the sitter’s hands and up the white dress to the calm oval of the face. Cross into the window: count the red bars; rest on the turquoise beyond; notice the palm’s dark green wedge. Slide back along the mullion to the wallpaper’s brown scrolls; return to the bouquet. Each circuit clarifies the painting’s grammar: warm and cool in balance, pattern as structure, poise as meaning.

Conclusion

“Woman Seated at Her Dressing Table” is a model of Matisse’s late Nice ideals. It fuses portrait and still life, interior and view, with disciplined color and a humane light that dignifies everything it touches. The woman’s presence is not dramatized; it is tuned—held in an environment where small objects, patterns, and a slice of sea conspire to create calm. The picture demonstrates how the ordinary can become orchestral when relations are exact. Nearly a century later, it still offers the quiet, usable wisdom Matisse prized: arrange the room, open the window, place a few living notes of color, and let attention do the rest.