Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

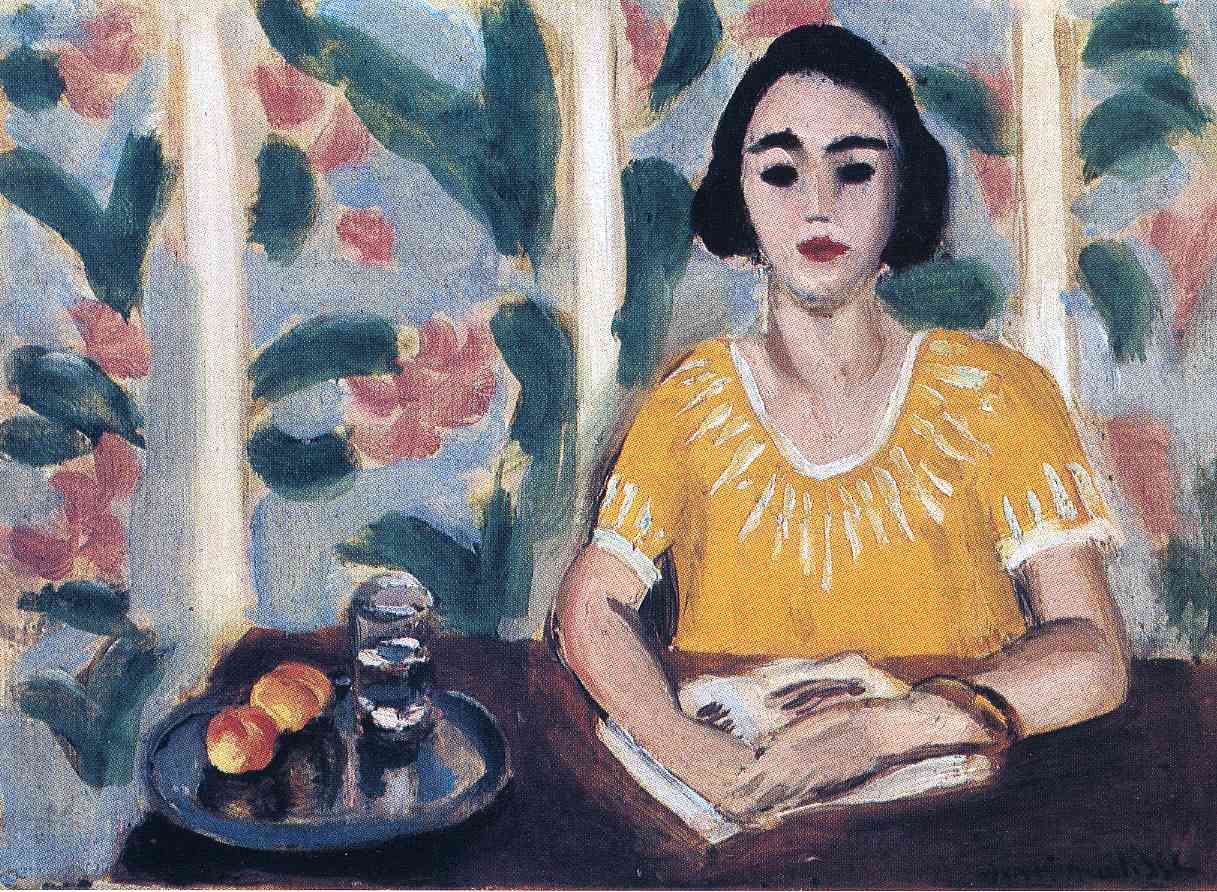

Henri Matisse’s “Woman Reading with Peaches” (1923) is a concentrated vision of calm attention staged within an interior that pulses with color and pattern. A woman in a golden blouse sits at a table with a book, while a metal tray holding two water glasses and a pair of peaches anchors the left foreground. Behind her, broad, leafy motifs and soft pink blooms spread across a pale wall like a textile. The scene is intimate, unhurried, and saturated with light. In this painting, Matisse refines the language of his Nice period—compressed space, ornamental surfaces, and an economy of drawing—into an image where reading, fruit, glass, and foliage become components of one measured harmony.

Historical Context and the Nice Period

After 1917, Matisse worked for long stretches in Nice, preferring bright but temperate interiors that allowed him to paint from the model day after day. The Nice pictures shift away from the shock effects of Fauvism toward a poised orchestration of color and contour. Everyday activities—listening to music, writing, sewing, or reading—provided structures for quiet concentration. “Woman Reading with Peaches” belongs to this world of domestic theatre. The subject’s serenity echoes the artist’s own practice: sustained attention, small adjustments, and the search for balance. The year 1923 falls at the center of this mature language, when Matisse used decorative pattern not as accessory but as a generator of space and rhythm.

Composition and the Architecture of Attention

The composition is built around a horizontal table that stretches edge-to-edge like a stage. The reader occupies the right half, her forearms forming a closed triangle atop the open book. This triangular scaffold gathers the figure’s energy inward and locks the image to the tabletop. On the left, the tray with glasses and peaches answers the mass of the figure, establishing a counterweight that keeps the rectangle from listing. Upright columns in the background—creamy vertical bands between patterned sections—segment the wall and serve as quiet pilasters behind the figure’s head and shoulders. These intervals of solid light allow the leafy motifs to breathe and prevent the surface from becoming a continuous carpet of ornament. Everything is measured to hold the reader’s pose steady without stiffness.

Color Climate and the Role of Yellow

The dominant chromatic force is the sitter’s blouse—an intense, sun-warmed yellow edged with small white flicks that radiate like stitched rays around the neckline. Matisse treats the garment as a regional climate that warms the right half of the picture. Across the room, he lays a cooler counterfield of gray-blue patterns and deep green leaf-forms that keep the yellow from becoming sugary. Within the still life, the peaches repeat the blouse’s heat but in lower saturation, while the gray metal tray and crystalline glasses cool the palette again. Skin is modeled with mild creams and faint violets that harmonize with the wall’s cooler passages. The overall effect is an equilibrium of warmth and freshness, like a garden room in late afternoon.

Pattern and the Decorative Field

The floral-leafy wall is not a literal window view; it is a decorative field that acts as space. Large, rounded leaves, brushed in with dense green, alternate with soft pink flower-clouds, their edges feathered so that the motif reads as paint before it reads as botany. The cream verticals between patterned bands act like seams in a hanging textile or mullions in a screen. Ornament here is Matisse’s spatial instrument: it establishes depth by layered flatness rather than by linear perspective. As the eye moves across repeating leaves and blossoms, it receives distance as rhythm—near-far not by vanishing points but by the interval between motifs. This is central to the Nice period’s modernity: space constructed through pattern.

Drawing, Contour, and the Face

Matisse’s drawing is spare and exacting. The head is a set of decisive arcs—the hair’s enclosing curve, brows like dark tilde-marks, succinct eyelids, a small weighted nose, and lips of concentrated crimson. He avoids fussy modeling; instead, brief temperature shifts—cooler under the jaw, warmer along the cheek—suggest volume. The neck is cut with two strokes that meet the blouse’s whitened edge, a junction that vents brightness upward toward the face. This economy of line preserves the painting’s freshness and keeps the figure integrated with the decorative field. The face does not detach into portrait realism; it remains one calibrated element among many.

The Book as a Rectangle of Thought

The open book is an understated but crucial shape. Its pale pages repeat the proportions of the canvas in miniature: a flattened rectangle scattered with darker marks. That echo insinuates the painting’s self-awareness—the idea that a page of text and a painted surface are siblings in the family of signs. The book’s cool whites relay light from table to blouse to wall, guiding the eye on a slow circuit. The posture—forearms framing the page, hands loosely meeting—embodies the absorption of reading without theatrical cues. The book becomes a visual metaphor for the discipline of attention that also organizes the canvas.

The Still Life of Glass and Peaches

At left, the tray introduces a different register of looking. The two cylindrical glasses stack reflections: white highlights, dark ellipses, and faint echoes of surrounding color. Glass lets the room flow through it; it clarifies by containment. The peaches supply a counterweight of matte solidity—tactile, fragrant forms nestled on burnished metal. Their orange-gold skin reprises the reader’s blouse while their rounded silhouettes rhyme with the leafy forms behind them. The trio—tray, glasses, peaches—establishes a triangle of their own that balances the figure’s triangular pose. The still life is not a separate genre inside the painting; it is a complementary phrase in the same visual sentence.

Light and the Refusal of Hard Shadow

Light is ambient, arriving from everywhere rather than from a staged lamp. Shadows are cool and transparent: under the chin, along the inner arm, beneath the tray’s rim. Matisse avoids browns and blacks that would weigh the image down; he prefers blue-grays and violets that keep chroma alive even in shade. The yellow blouse does not shade into mud; it cools toward olive and then lifts again into lemon membranes where white is scrubbed across the surface. This breathing, veil-like handling produces the sensation that the room itself emits light. It also fuses figure and interior into one atmosphere, consistent with the Nice period’s serene temperament.

Space Without Deep Perspective

The table’s surface is a dark, gently tilted plane; the wall behind behaves like a textile hung close to the picture plane. There is little illusionistic recession. Instead, Matisse constructs depth by layering: still life in front, reader at the plane of the table, pattern field behind. The cream verticals and the softer patches around them imply columns or window frames, but they function primarily as color intervals. This compression allows color and pattern to carry the experience of space, keeping the viewer near the subject while avoiding claustrophobia. The result is intimacy without enclosure.

Rhythm, Silence, and the Time of Reading

The painting’s tempo is deliberate. Repeated leaves thrum softly behind the sitter; the bright “stitches” around the neckline flutter like a quiet fanfare; the glasses’ stacked circles tick like a transparent metronome. Yet the dominant feeling is of silence—the kind that accompanies focused reading. Matisse paints not narrative but condition. The reader is captured in that threshold between seeing and thinking, and the room holds the moment still. In this way, the picture aligns with other Nice interiors that celebrate cultivated leisure, treating attention itself as a modern subject.

Psychology and Poise

The woman’s expression is reserved, inward, and slightly solemn. Her gaze drops toward the book; the mouth holds color but no smile. Rather than pry into personal identity, Matisse presents a formal state: self-possession. The squared shoulders and centered head keep the composition upright; the hands’ relaxed clasp prevents rigidity. The blouse’s radiant yellow would tip toward exuberance if not for the face’s composure; the two hold one another in check. This balance—sensual color moderated by dignified pose—marks the ethical tone of the Nice period: pleasure understood as equilibrium.

Material Presence and the Touch of Paint

Despite its calm, the surface is lively. In the wall, large leaves are punched in with loaded, dark brushes; pinks are laid in quickly and left to fray at their edges. Along the blouse, white dashes describing the collar’s embroidery are placed in a single pass; they are not blended or corrected. The table’s dark glaze is scumbled thinly so that the canvas texture picks up light. In the glasses, highlights are small impastos that physically catch illumination. These varied touches give the work tactile interest and keep it visibly handmade, preventing the decorative order from becoming sterile.

Parallels and Variations Within 1923

Seen alongside Matisse’s 1923 “Woman in Yellow,” “Woman Leaning,” or “Reader Leaning Her Elbow on the Table,” this painting offers a more frontal, simplified arrangement. It replaces the set-piece drama of curtains and doorways with a shallow stage and a quieter still life. Yet the structural logic is shared: a single dominant garment color, blue-green decorative fields, and a calm, centered figure. The peaches reprise the Nice studio’s recurring motifs of fruit and glass, while the blouse’s stitched-ray neckline anticipates later works where embroidery and dressmaking become key ornamental partners to the figure.

Looking Closely: A Guided Circuit

Begin at the brilliant neckline—those white slivers radiating outward like stitched sunbeams. Let your eye slide down the blouse’s warm plane to the clasped hands and pale book pages. Cross the table to the tray and watch reflections assemble and dissolve in the water’s stacked ellipses. Lift into the wall’s leafy rhythm; register how each leaf is both a plant form and a confident brushstroke. Return to the face and notice how few marks carry its entire presence: the arch of the brow, the thick lashes, the slight shadow under the lower lip. With each circuit, the painting reveals its logic—attention bred by repetition, serenity achieved through measured contrast.

The Ethics of Pleasure and the Modern Interior

Matisse often described his aim as offering an art of repose. In “Woman Reading with Peaches,” that ideal becomes concrete without becoming complacent. Pleasure is calibrated: the tongue of peach color, the cool of metal and water, the soft friction of leaf against bloom. The modern interior is not a place of spectacle but of cultivated quiet. The painting proposes that beauty is available in ordinary arrangements—fruit on a tray, a page on a table—when perceived with disciplined tenderness.

Conclusion

“Woman Reading with Peaches” distills the Nice period’s characteristic poise. A luminous blouse, a rhythmic wall, a simple still life, and a composed face become components of one balanced chord. The painting’s innovations lie in its methods: space built from pattern, light held in color rather than shadow, and human presence rendered with austere drawing. In this small domestic moment, Matisse demonstrates how attention can be pictured and how a room can be tuned until it sings softly around a person who reads. The result is an enduring image of modern tranquility—sensual, intelligent, and clear.