Image source: wikiart.org

A moment of quiet modernity

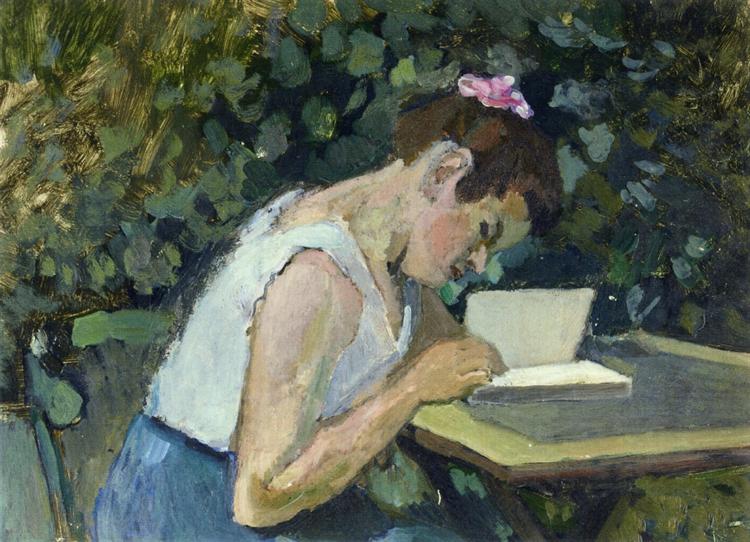

Painted in 1903, “Woman Reading in a Garden” captures a hushed interval of concentration at the threshold of Matisse’s stylistic transformation. The subject is simple—a young woman bends over an open book at a small outdoor table—but the painting is charged with the discoveries that would soon power Fauvism: color that carries form, brushwork that announces itself, and a surface that hovers between depiction and decorative pattern. Within this modest rectangle Matisse turns private reading into a drama of light and hue.

First impression: intimacy framed by foliage

At first glance the figure registers as a wedge of pale values set against a thicket of greens. Her white blouse, blue skirt, and the pink rosette pinned in her hair glow against a background of rounded leaf-forms. The tabletop tilts slightly toward us, the book lies open like a folded wing, and the woman’s profile is caught in that absorbed posture recognizable anywhere someone reads outdoors. Nothing distracts the eye beyond these essentials; the garden is a soft enclosure, a living backdrop for the act of attention.

Composition built from diagonals and nested shapes

Matisse composes the scene as a series of nested angles. The woman’s bowed head, neck, and forearm make a diagonal that echoes the angle of the tabletop and the book’s spine. Those diagonals cut across a system of rounded forms—the arc of shoulder, the curve of the hair bun, the ellipses of leaves—so that hard and soft shapes interlock. The figure occupies the picture’s left half, but the mass of foliage on the right balances her presence and keeps the image from tipping. The result is an asymmetrical calm: one side active with figure and table, the other dense with vegetal rhythm.

The psychology of absorption

By choosing a profile view and hiding the reader’s eyes beneath her brow, Matisse tells us this is not a portrait of a personality performing for the viewer. It is a portrait of attention itself. The hand pinching a page, the forward lean of the torso, the near-touch of nose to paper—all convey an inward turn. The garden is public space, yet the reader’s concentration makes a room of her own. That psychological privacy mirrors Matisse’s own studio privacy; reading, like painting, is a solitary negotiation between a mind and a surface.

Palette: greens as climate, cools and warms in conversation

The painting breathes green. Sap greens, olive notes, and bluish viridians mingle with yellowed dabs to create a climate rather than a catalog of leaves. Against this green climate Matisse places the figure in cool lights—milk-white blouse tinged with lavender, blue skirt modulated with slate and teal, flesh modeled by alternating warm and cool halftones. The tiny pink hair ornament is a deliberately high note; placed near the head’s apex, it punctuates the composition and prevents the upper left from dissolving into tonal sameness. Nothing is garish; all is keyed to the calm of an overcast garden afternoon.

Light as a soft envelope

There is no harsh sun here. Illumination behaves like a veil that lays evenly across surfaces. Whites are never chalk; they own a tint of surrounding color, so the blouse reflects garden greens and blue-violet shadows. Flesh turns not by black shading but by temperature shifts: warm ochres trade places with cool lilacs along the cheek, neck, and forearm. This atmospheric light preserves the painting’s unity. Because no one highlight screams, color relationships do the structural work and keep the viewer moving.

Brushwork and surface tactility

Matisse lets the brush speak differently in each zone. Background leaves are laid with half-loaded, rounded touches, often allowing the ground to peep through, so the foliage shimmers as though stirred by air. The blouse is painted with longer, pliant strokes that follow folds and edges, stating volume without fuss. The book’s pages are handled with flatter, broader pulls, emphasizing their planar nature. Across the painting the paint sits with modest body, neither glossy nor heavily impastoed, which suits the theme of quiet concentration. Yet the surface is alive; you sense the speed and pressure changes of a hand that edits as it goes.

Drawing by adjacency, not outline

One of Matisse’s defining moves in these years is to draw with color contact. The contour of the neck is the place where a cool lilac meets a greener shadow. The book’s edge appears because pale paper presses against the gray-green tabletop. Only at a few junctures—under the chin, along the table’s angle, at the near edge of the book—does he tighten a darker seam to clinch the form. This chromatic drawing builds forms that feel soft-edged, human, and bathed in air.

The garden as decorative field

While the foliage records a natural setting, it also operates as a patterned field. Circular and almond-shaped touches repeat with variations, like motifs in a printed textile. This decorative tendency, absorbed from Gauguin and the Nabis, does not flatten the scene; instead it grants the background a steady pulse against which the figure’s diagonals read crisply. You feel the garden less as a mapped space than as a living tapestry.

Geometry of table and book

The slanted tabletop and the open codex introduce simple geometry that clarifies the scene. The table’s two visible edges form a shallow wedge that points toward the woman’s hands—the picture’s narrative center. The book, with its V-shaped opening and crisp rectangular pages, acts as a small white beacon. Even in a green-toned composition, that patch of near-white pulls the eye. Matisse understands that in a reading picture, the book must be both object and light source; it is the reason for the pose and the illumination of the mind.

Depth kept shallow, unity kept high

Spatially the painting is shallow. Leaves crowd close, the tabletop tilts up, and there is little sense of far recession. This shallowness is intentional. It binds the figure to her setting and keeps the surface behaving like a single fabric. A deeper space would invite wandering; Matisse prefers focus. The shallow depth also lets the patterned foliage and the planar table read as equal partners in a decorative whole, anticipating the flattened spaces of his later interiors.

Influences in play: Cézanne, Renoir, Bonnard, and the Nabis

Cézanne’s lesson is visible in the way volumes are turned through adjacent color patches rather than slick modeling. From Renoir comes the theme of women in gardens, though Matisse strips away voluptuous fleshiness for a leaner, more thoughtful presence. Bonnard’s domestic intimacy and love of patterned vegetation lurk nearby, yet Matisse’s drawing is firmer and his color relations cooler. The Nabis’ belief in the painting-as-tapestry is palpable in the background’s ornament-like rhythm. All of these currents pass through Matisse’s sieve and emerge as a language that looks unmistakably his.

Position in Matisse’s 1903 trajectory

In 1903 Matisse paints several interiors and still lifes that test how much color and pattern can organize a composition. “Woman Reading in a Garden” acts as the outdoor pendant to that research. The subdued yet resolute palette, the chromatic drawing, and the equilibrium between figure and decorative field are exactly the problems he would push to a blazing extreme in 1904–05. Here, the fire is banked, but the logic is already in place.

Gender, literacy, and modern life

The reader participates in a wider iconography of modernity: individuals—especially women—claiming time for private study in public or semi-public spaces. The painting sidesteps anecdote and moralizing; there is no title, author, or narrative clue. Instead, the act of reading itself becomes a sign of interiority and self-possession. The modest clothes and practical hairstyle resist the era’s salon glamour. Matisse treats the subject with respect and sobriety, aligning everyday intellect with his own artistic work ethic.

Time of day and sensory cues

The light’s softness suggests late morning or midafternoon, the wind calm enough to leave leaves still. Color temperature hints at mild weather rather than heat. The tabletop’s slant and the firm arm create a faint sense of motion—as if the reader might at any moment turn a page. These cues make the painting feel like a captured minute, not a posed eternity.

Likely palette and technical choices

The harmony points to a practical early-1900s kit: lead white moderated with small tints for the blouse and paper; yellow ochre and raw sienna in the warm halftones of flesh; ultramarine and cobalt for skirt and shadow cools; viridian or terre verte tempered with ochre for garden greens; raw umber and a touch of ivory black to stabilize the darkest accents; rose madder or a cadmium red light for the hair ornament, carefully cooled so it does not burst out of key. Much of the paint appears scumbled thinly over a toned ground, especially in foliage, so the weave of the canvas participates in the leafy texture.

How to look to get the most from it

Start with the book, then trace the zigzag from page to fingers to wrist to elbow to face. Once you reach the pink rosette, let your eye circle through the foliage, noting how repeating leaf shapes establish a rhythm, then return to the book via the slanted table edge. Move closer to see small color decisions—the lavender along a blouse seam, the green reflected under the jaw. Step back again to feel how the figure’s pale wedge and the green field lock together like two pieces of a puzzle. The painting rewards this slow oscillation between detail and whole.

What the painting tells us about Matisse’s priorities

Above all, it shows Matisse trusting color to do nearly everything: model form, locate space, deliver mood, and maintain unity. It shows him willing to simplify when simplification clarifies, to let a background become a pattern when pattern better conveys sensation than meticulous leaf-by-leaf description. And it shows his respect for ordinary, concentrated acts—reading, working, arranging—as worthy of pictorial ceremony.

Enduring significance

“Woman Reading in a Garden” endures because it joins tenderness and rigor. The tenderness is for the reader, for the quiet dignity of her task, for soft light on skin and paper. The rigor is in the painting’s engineering: an armature of diagonals, a tuned palette, and a surface that never forgets it is paint. In later years Matisse would amplify color to symphonic volume, but the virtues on display here—clarity, economy, and a pleasure in looking—remain the backbone of his art. The painting is a small thesis on how to see: attend carefully, simplify responsibly, and let color carry truth.