Image source: wikiart.org

A quiet beginning for a revolutionary painter

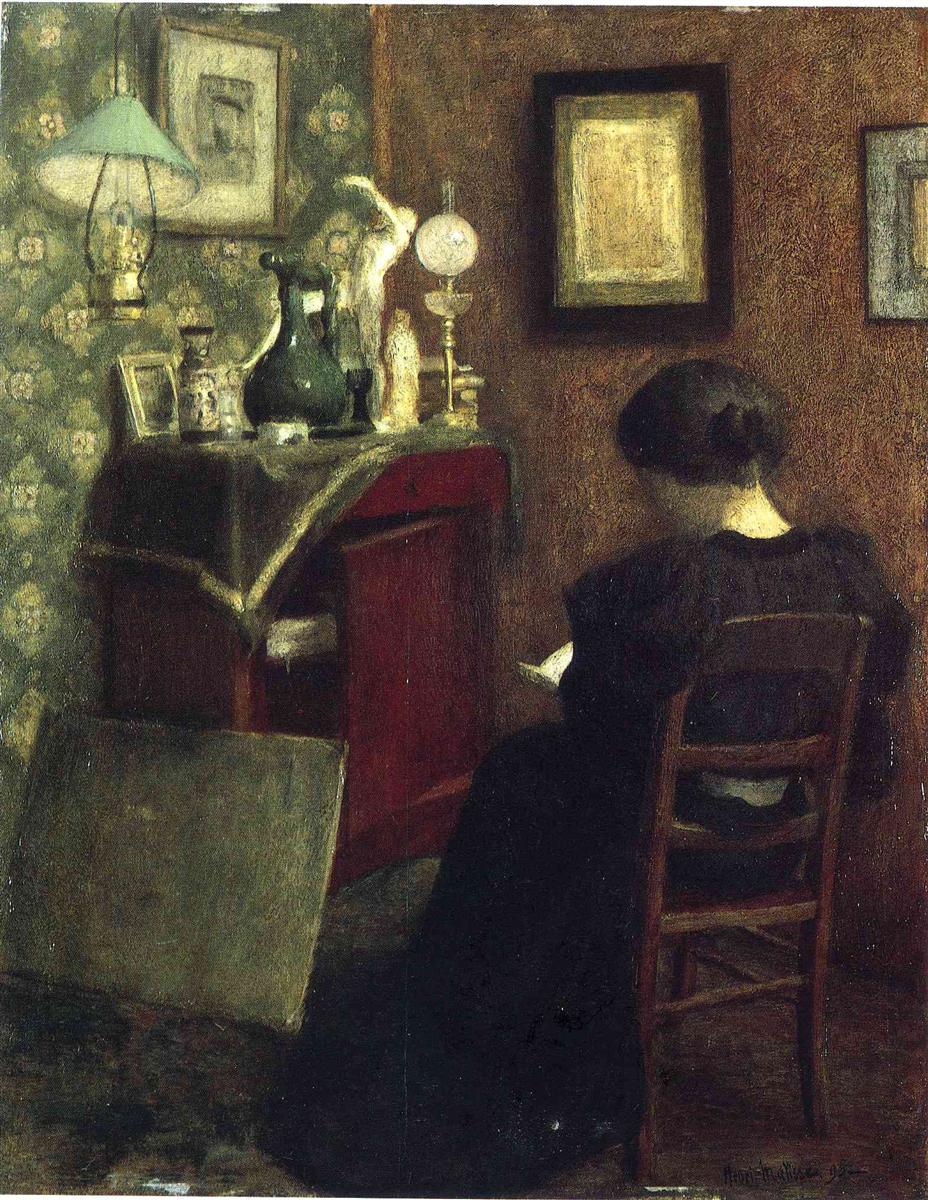

Henri Matisse’s “Woman Reading” of 1894 captures an unexpectedly hushed moment in the early career of an artist better known for radiant color and bold simplification. The scene is an intimate interior: a seated woman turns away from us, absorbed in a book, while a corner cabinet crowded with vessels, photos, and an oil lamp anchors the opposite side of the room. Patterned wallpaper, framed pictures, and a scattering of household objects complete the atmosphere of a modest bourgeois home. Nothing dramatic occurs, yet the painting feels weighted with presence. This is Matisse learning to make a room breathe, and to let attention itself become a subject.

Historical context and what 1894 meant for Matisse

In 1894 Matisse was still forming his craft. His training had emphasized drawing from the model, copying old masters, and building tonal control before pursuing expressive color. The influences running through this canvas include seventeenth-century Dutch interiors, Chardin’s still lifes of the eighteenth century, and the sober naturalism of late nineteenth-century academic practice. “Woman Reading” belongs to the moment when Matisse mastered the grammar of value and edge, the patient notational skills that would later allow his chromatic daring. The painting is not a detour from his destiny; it is the foundation of it.

The composition’s inward turn

The composition rotates around two masses. At lower right sits the dark triangular body of the woman, her back softly illuminated as she leans toward a small book. At upper left the cabinet presents a vertical counterweight, stacked with objects whose silhouettes interlock like chess pieces. The space between them—an open wedge of floor and wall—forms the painting’s silent core. By refusing to show the reader’s face, Matisse diverts the drama away from expression and into posture, shadow, and placement. The viewer’s eye traces a slow arc from the woman’s bowed neck to the white edge of her page, then across the diagonal to the pale lampshade, before circling back along the framed pictures on the wall. The room encourages contemplation in the same way the act of reading does.

Orchestrating rectangles and curves

One of the canvas’s pleasures is the way geometry underwrites its mood. Rectangles abound: the backs of frames, the door of the cabinet, the canvas leaning on the floor. Against this grid Matisse arrays supple curves—the rounded shoulder and bun of hair, the belly of a green carafe, the dome of the lampshade, the serpentine edge of a tablecloth. The alternation between hard and soft outlines prevents stagnation and guides attention from surface to surface. The chair’s vertical slats echo the frames while its arcing crest rail rhymes with the woman’s shoulders, knitting figure and furniture together. These rhythms are quiet, almost subliminal, and yet they create the sense of an interior as a living order rather than a pile of things.

Light as narrator

Light here is not bright; it is a gentle, woolen illumination that seems to emanate from the unseen window to the right and to be held in reserve by the oil lamp on the cabinet. Matisse controls value with unusual tact for a young painter. Background walls hover in mid-tones, the cabinet sits in a warm penumbra, and the woman’s dress reads as a single mass of deep value, relieved by a narrow highlight on her neck and the wedge of white paper in her hands. Those small lights carry narrative weight: the paper glows because the mind behind it is awake; the porcelain figurine on the cabinet catches a sliver of illumination, as if memory itself were lit in that corner.

The palette’s held breath

The color range is restrained: olive greens, umbers, tobacco browns, softened blacks, and chalky creams. There is no flamboyance, yet the harmony is rich. The wallpaper’s muted floral pattern supplies a gentle pulse of cool greens that temper the warmer siennas of the opposite wall and cabinet. The green glass bottle at left provides a concentrated chromatic anchor, its dark body absorbing light while offering small olive highlights. The woman’s dress remains almost monochrome, which allows her skin and the white page to register more vividly. This reserved palette anticipates Matisse’s later understanding that color speaks most eloquently when it is paced, not shouted.

The psychology of the turned back

By showing the reader from behind, Matisse creates a paradox. We cannot see her expression, yet we feel her interiority more intensely. The bowed head and compact posture suggest absorption rather than melancholy. Her isolation is chosen, not imposed. The world of illustrated frames and treasured objects lies around her like a halo of associations, but the focal event is the convergence of hand, page, and light. In the act of reading, the figure becomes a still life of attention. This is a portrait of a mind at work that preserves the sitter’s privacy.

A theatre of objects

The cabinet functions as a small stage on which objects perform. A figurine lifts a gesture of dance; a glass goblet collects a quick white reflection; a porcelain jar offers a matte counterpoint to the bottle’s sheen. Even the cloth that trims the cabinet lifts at the corners like curtains. Matisse arranges these items not as inventory but as actors in a visual sentence. Their varied surfaces—glazed ceramic, clear glass, dull metal, buffed wood—allow him to practice translating material into paint. Each object records a different kind of light, and together they demonstrate the painter’s growing ability to modulate reflection, absorption, and texture without overstatement.

Texture, touch, and painterly restraint

Up close the surface reveals small, deliberate strokes. The wallpaper’s floral rosettes are indicated with economical touches of cool pigment; the brown wall carries a granular scumble that suggests plaster; the bottle’s highlights are pulled with a loaded brush and then slightly softened, so that they breathe. The white figurine on the cabinet is modeled with a restricted range of half-tones—barely more than two values—but the paint sits dense and confident, giving the porcelain a tactile weight. This measured facture is the opposite of bravura. It signals patience, an ethical respect for the modest subject.

Framing the act of looking

Framed pictures within the painting echo the act of painting itself. The most luminous of them—a pale rectangle with a dark border—glows against the brown wall like a blank page. Matisse makes it the brightest planar shape in the room after the book, establishing a rhyme between reading and viewing. A picture is another kind of page; attention is the true protagonist in both. The frames also mark the wall as a site of memory, full of images that sustain the room’s inhabitants. The woman reads, and around her the artifacts of previous looking keep watch.

The space you can feel

Although the room is compact, Matisse opens it with subtle spatial cues. The table tilts slightly toward us, welcoming inspection. The floorboards gather into a shallow wedge that points our eye into the corner. The chair crops the figure, but a sliver of floor at lower left and the receding cabinet create enough air that the space never feels claustrophobic. The canvas leaning against the wall at lower left breaks the flatness and quietly announces the painter’s presence. We are in a working room, not a stage set.

Time folded into things

The scene suggests lived duration. The lamp is not lit, implying daytime; the wallpaper is slightly worn; the cabinet’s cloth is frayed; frames hold old photographs and drawings; a bottle appears to have been handled often; the chair’s rung shows subtle wear. None of this is stressed, but the cumulative effect is of a room where time gathers without drama. Reading becomes one more way time is transformed into meaning. In that sense the painting extends a theme common to Dutch interiors and to Chardin: the dignity of ordinary time.

Echoes of Chardin and the Dutch

Connections to earlier traditions are clear but never slavish. Chardin’s influence reads in the gravity with which modest objects are honored, the careful spacing of vessels to give each a pocket of air, and the balanced rapport between cool and warm values. The Dutch presence is felt in the corner composition and the attention to wall ornament, lamps, and framed images. Yet the overall mood is distinctively fin-de-siècle—quieter, more introspective, less moralizing than its seventeenth-century models. Matisse is not staging a lesson; he is staging a state of mind.

Narrative held in reserve

What is the woman reading? A letter, a novel, a devotional? Matisse refuses to specify, and the refusal is part of the painting’s grace. He offers just enough detail—the intimate domestic setting, the solitary figure, the lavish attention to her small book—to invite the viewer’s own memories of concentration. The painting becomes a mirror for our experiences of reading in quiet rooms, of hearing the soft hinge of a page while the world hums around us.

The ethics of attention

A deeper theme quietly emerges: the ethics of looking closely. Matisse’s later career would celebrate art’s capacity to provide “an armchair for the tired businessman,” a phrase often misread as escapism. In truth, his ideal of repose is a moral one, linked to clarity, balance, and a certain inner poise. “Woman Reading” already enacts that ethic. The artist pays attention to the simplest things until they repay the attention with presence. The viewer, in turn, learns to pay attention by following the painting’s calibrated signals—highlight, edge, texture—toward a still center.

Lessons for the colorist to come

Even in this subdued palette, one can feel the seeds of the later colorist. The green bottle anticipates the role a saturated accent will play in his Fauvist interiors; the contrast between the woman’s dark silhouette and the surrounding walls prefigures the flat-patterned figures of 1908–1911; the compositional economy—two great masses, a few key accents—foreshadows the powerful simplicity of his mature arrangements. By mastering tonal painting here, Matisse frees himself later to deploy color with conviction, because he knows how structure carries an image even when chroma is restrained.

The sound of silence

Many early interiors by young painters feel contrived, but this one persuades through its sound. You can almost hear the faintest noises: the turning of a page, the soft sibilance of a distant street, the creak of a wooden chair, the tiny glassy tick if a vessel on the cabinet were gently touched. The painting’s silence is not emptiness; it is a resonant hush created by the balance of forms, values, and textures. This acoustic quality is part of why the work lingers in memory.

The dignity of the sitter

Although the woman’s face is hidden, Matisse treats her with a tenderness that resists objectification. There is nothing coquettish or theatrical in her posture. She is a person allowed to have a private life in paint. The care with which the neck is modeled and the book is held suggests an intimate knowledge of how a body adjusts itself when it reads—wrists relaxed, head slightly inclined, shoulders surrendered to the chair’s back. The painting’s respect lies in precisely recording these ordinary truths.

The domestic interior as a world

For all its modest scale, the painting maps a complete world. It includes light source and reflective surfaces, art and craft, work and leisure, public space (pictures on the wall) and private space (a person alone with a book). The still life on the cabinet speaks to history and memory; the figure speaks to the present moment; the empty chair back and the leaning canvas hint at the artist’s own place in the room. The interior becomes a synthesis of relationships rather than a container of stuff.

Material thinking and the touch of paint

Metaphor quietly attaches to mediums within the scene. Oil lamp and oil paint share a luminous capacity; paper page and primed canvas echo one another; glass and varnish catch related sparks. Matisse’s brush translates each material into a pictorial equivalent without pedantry. The lesson is that painting is not only about seeing but about thinking materially—understanding how a surface holds or rejects light, how edges either dissolve or sharpen. This is the kind of thinking that later empowers him to flatten forms boldly without losing their presence.

An early credo of equilibrium

The most enduring impression the painting leaves is equilibrium. Dark and light, curve and line, mass and void, object and person, looking and reading—all stay in sympathetic balance. Nothing dominates or declaims. That equilibrium will remain a hallmark of Matisse’s art even when his colors roar. He often spoke of seeking “serenity” in his pictures, a sense of balance that calms without dulling. “Woman Reading” is one of the first places where that credo appears fully felt.

Conclusion

“Woman Reading” is a meditation on attention rendered with the tools of tone, texture, and modest color. It demonstrates how a young Matisse learned to orchestrate a room so that every object contributes to a quiet drama, how he used light to turn matter into meaning, and how he honored the private act of reading by building a sanctuary around it. Far from being merely a student exercise, the painting is a statement of values—the dignity of the everyday, the sufficiency of simple forms, and the power of stillness. From this quiet interior, the future master of color would step into blazing rooms; but he would carry with him the equilibrium and restraint he learned here.