Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

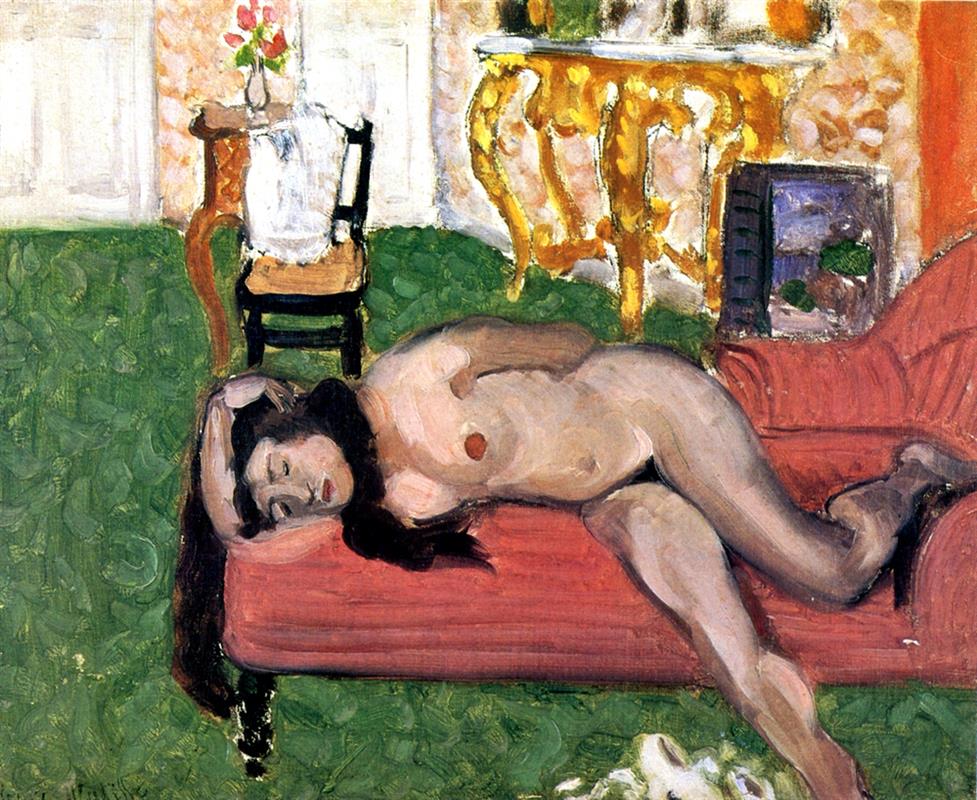

Henri Matisse’s “Woman on a Couch” (1919) presents a sleeping nude stretched across a coral-pink daybed in a shallow, ornamented room. The figure lies diagonally from lower left to right, one arm folded behind the head, the other falling along the ribs; dark hair pools over the upholstery, and the soft weight of the body is described with quick, decisive planes of warm grays and rose. Around her, a green patterned carpet, a black chair topped with a vase of flowers, a white cloth, and a gilded console create a domestic stage. The painting is at once intimate and openly constructed: it reveals the studio’s furniture and the painter’s touch without theatrical concealment, turning the traditional reclining nude into a modern composition of color, rhythm, and light.

Historical Context

Painted in the first year after the Armistice, the work belongs to Matisse’s early Nice period. Having weathered the disruptions of the war, he turned to interiors and to the ordinary rituals of looking—reading, resting, opening shutters to the sea. These subjects are not escapist; they are deliberate attempts to rebuild harmony through the ordering powers of color and pattern. In 1919 he repeatedly explored the nude on a couch or chaise, but he relocated the odalisque tradition from exotic fantasy to the truth of the studio. The furniture is recognizable, the light is Mediterranean and even, and the emphasis falls on pictorial balance rather than on narrative display.

Motif and First Impressions

At first glance, the painting balances two worlds. In the foreground, the body sleeps with a trust that implies companionship between model and painter. In the background, domestic objects quietly proclaim the room’s life: a chair with a white drape, a slim vase with bright blossoms, the witty flourish of a rococo console, and a small framed picture that leans casually against the wall. The viewer senses a day in progress—flowers freshened, cloth tossed aside, furniture put to use—while the figure rests in the midst of it, turning the studio into a theater of calm.

Composition and the Diagonal Body

The composition pivots on the diagonal of the nude. The head anchors the left corner, the knees break gently at the right, and the daybed’s horizontal edge defines a stage on which the body performs its long S-curve. This diagonal is answered by counter-diagonals in the furniture: the gilt table legs sweep upward; the chair’s back slants toward the vase; the small picture leans. Together these vectors keep the surface energized while the wide horizontals of carpet and wall prevent agitation. Cropping is decisive—the couch runs out of frame at right—so the viewer is drawn close, as if stepping into the scene rather than observing from a distance.

The Architecture of Color

Color builds the space. The green carpet, mottled with leafy swirls, forms a cool ground plane that carries hints of garden and air. The pink couch is a warm counterweight, its ribbed strokes setting a soft tempo beneath the body. The walls move from creamy white panels to a peach and white texture that reads like patterned paper or washed plaster, giving a middle register between carpet and couch. Then comes the gold: the console’s luminous volutes inject a concentrated heat that echoes in the vase’s stems and the small warm dabs across the wall. Against these large fields, the flesh tones settle into harmony—warm where light rests, cooler where weight gathers. The palette is restrained yet sumptuous, a Nice-period hallmark: comfort without glare.

Light and Atmosphere

Light is diffuse, likely from high windows, and it softens the modeling rather than carving deep shadow. The body is turned by temperature shifts—cool grays along the abdomen and thigh, warmer notes on shoulder and hip. The couch reflects rose into the limbs, binding figure and furniture. There are few cast shadows; forms meet each other gently, preserving the sensation of a quiet interior in which time drifts rather than strikes. The even light lets color do the expressive work, and it supports the painting’s ethical tone: nothing is dramatized at the expense of the sleeper’s privacy.

Pattern as Structure

Pattern unifies the room. The carpet’s leafy motifs, the ribbed upholstery, the pale repetitions on the wall, and the rococo curls of the console all speak the same ornamental language. Matisse scales the patterns to their tasks: broad and rhythmic underfoot, more insistent in the gilded table, barely there on the wall, and linear across the couch. The nude, largely unpatterned, becomes the quiet center to which these decorative voices return. Pattern is not accessory but architecture, distributing energy across the surface so that no single element overpowers the whole.

Drawing and the Living Contour

Contour is present and elastic. A dark, confident line runs along the back and thigh, thins at the ankle, and thickens again around the shoulder; elsewhere, forms meet through adjoining planes rather than hard borders. The head, with closed eye and slack mouth, is written in a few strokes that say enough and then stop. The furniture receives the same quick authority: the chair’s legs flick into place; the console’s scrolls are painted with a calligrapher’s wrist. These lines are not corrections; they are the scaffolding on which color rests, keeping the picture lively and honest.

Material Presence and Brushwork

The painting never hides its making. On the couch, long ridges of paint reproduce the feel of ribbed fabric. In the carpet, the brush dances in curving taps that become leaves without pedantry. The walls are scumbled thinly so the weave of the canvas breathes through, and on the gold console the pigments sit a little thicker, catching light like gilded wood. On the body, strokes follow the anatomy—long along the thigh, circular over the hip—so that form grows from gesture rather than from analytic detail. The viewer experiences not only the scene but the tempo of its creation.

Space: Shallow, Breathable, Modern

Depth is shallow by choice. The couch and body press against the surface; the chair and console sit just beyond; the wall panels and small picture close the space. Overlap is sufficient to imply recession, but perspective never steals the show. This shallow arena lets color fields and patterns preserve their decorative integrity while hosting believable objects. It is a modern compromise between illusion and design, one Matisse mastered in Nice: the room invites habitation and, at the same time, insists on being paint.

Eroticism and Reserve

The nude is frank yet dignified. The sleeping face and the unposed hand under the head suggest trust; the body’s weight, not its display, carries feeling. A dark scarf or fall of hair runs along the neck, introducing a sober interval between shoulders and couch. There is no array of luxurious props designed to turn the model into fantasy; the studio’s ordinary furniture and a single bouquet suffice. The result is sensuality grounded in presence. The viewer is invited to share a moment of restful human warmth, not to consume a spectacle.

Studio Truths and Domestic Signs

The black chair with its white cloth, the small vase of flowers, the leaning picture, and the gilded console locate the nude in the reality of the studio. The cloth might be a dressing towel, the framed image a reference or a recently finished work. These inclusions matter because they anchor the odalisque motif in lived space. Matisse is not staging a distant “Orient”; he is arranging his own room—which is to say, arranging painting itself. The studio becomes a home for both body and art, and the picture honors this dual citizenship.

Rhythm and the Viewer’s Path

A natural path through the painting begins at the sleeper’s face, travels the long arc of shoulder, breast, hip, and knee, and then returns along the couch’s edge to the scatter of white at the lower center. From there the eye climbs the chair to the flowers, crosses the gilded console’s gleam, glances at the small picture, and drops again to the couch. This circuit is musical: a long legato across the figure, quick trills in the furniture, a bright chord at the gold table, and a soft cadence at the wall. The painting rewards lingering because every loop recomposes the scene.

Comparisons Within the 1919 Series

Matisse painted several recumbent nudes on pink couches in 1919. Compared with those, “Woman on a Couch” leans more heavily on the room’s decorative chorus. The carpet is greener and more assertive, the console brighter, and the background busier, which makes the sleeper’s stillness all the more persuasive. The composition also extends farther to the right, with the couch running out of frame, increasing the sense of proximity. The differences show how Matisse could retune the same ingredients—couch, carpet, nude, console—into distinct atmospheres simply by shifting emphasis and scale.

The Ethics of Economy

The painting’s economy is striking. The body is modeled by a few broad turns; the face is summarized in small, sure touches; the flowers are dashes; the console, though elaborate in real life, is rendered through a handful of curling passages. This restraint does not read as deprivation; it reads as confidence. Matisse gives each element just enough information to live on the canvas, then stops. The restraint confers respect: the model is not fussed over, nor are the objects fetishized. Everything receives attention at the scale of the whole.

Dialogue with Tradition

The reclining nude reaches back to Titian and Ingres, but Matisse brings it into the twentieth century by shifting the mode of persuasion. Instead of high finish and deep perspective, he offers frank brushwork and shallow space; instead of myth or allegory, he offers the truth of a room. The gold console may nod to rococo luxury, but it appears as a painted flourish, not as evidence of a fantasy harem. The lineage is acknowledged, then redefined as a conversation about color and construction.

Anticipations of Later Work

The ornamental rhythms of carpet and console, the emphasis on silhouette, and the clear figure-ground relationships anticipate the cut-outs of the 1940s. In those late works, leaf and arabesque would become pure shapes pinned against color. Here, while still bound to observed interiors, Matisse is already thinking in terms of repeated motifs and large planes. The seeds of the later language—clarity of edge, bold flatness, pattern as structure—are palpable beneath the oil’s softness.

Human Warmth and Climate

Everything in the picture communicates climate: the green coolness of the carpet, the warm drift of light across wall and couch, the way the body relaxes into that climate without tension. The bouquet on the chair is a small emblem of the room’s air; the white cloth thickens the sense of domestic ritual—bathing, dressing, resting. The viewer almost feels the hush of early afternoon, when shutters shade the floor and a person can fall into sleep. Matisse’s art of interiors is, at heart, an art of climates that sustain the body and the eye.

How to Look

To enter the picture attentively, trace the body’s diagonal once, slowly, letting the temperature shifts tell you where weight lies. Then linger on the places where painter and model meet most intimately: the reflection of pink on the thigh, the soft merging edge at the abdomen, the darker seam under the breast. Next, allow the furniture to speak: the chair’s handmade wobble, the console’s flourish done with a single curve of the brush, the small painting’s oblique rectangle. Finally, step back and let the carpet’s green rise toward you like cool air. This sequence does not fix your reading; it offers a way to feel the painting’s unity.

Conclusion

“Woman on a Couch” distills Matisse’s early Nice-period promises: that calm can be rebuilt from large, legible relations; that pattern is a structural ally of feeling; that a studio interior can host both human warmth and painterly clarity. The nude’s diagonal arc, the pink couch’s steady rhythm, the green carpet’s leafy murmur, and the gold console’s bright countertheme together compose an image that is intimate but never prurient, decorative but never shallow. In a year devoted to repair, Matisse discovered in such rooms a durable order—one supported by color, light, and trust. The painting still offers that order, inviting the viewer to rest with it, to breathe with it, and to recognize in its quiet music the generous possibilities of the everyday.