Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Setting And The Nice-Period Program

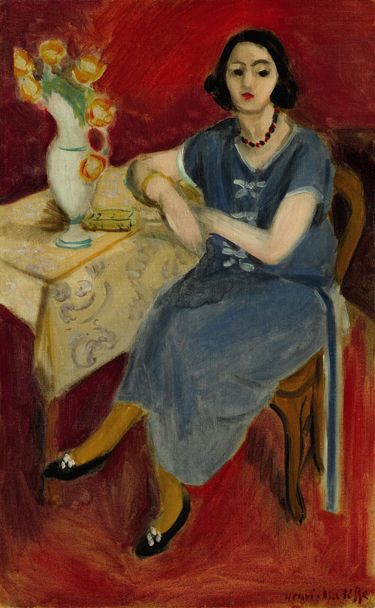

Henri Matisse painted “Woman in Blue at a Table, Red Background” in 1923, at the height of his Nice years. During this period he transformed quiet rooms on the Côte d’Azur into laboratories for light, color, and human presence. After the blazing experiments of Fauvism and the structural discipline of the 1910s, he sought a clear, breathable painting—one that replaced drama with lucidity and let color carry emotion. This canvas exemplifies that ambition: a seated woman in a blue dress, a small table with a white vase of flowers and a book or compact object, and a continuous field of red that saturates the room with warmth. The set is simple, but the orchestration is sophisticated. Matisse uses a spare cast of elements to build a world where pattern acts like architecture and calm poise becomes a modern subject in itself.

Composition As A Triangle Of Figure, Table, And Red Field

The composition is a well-balanced triangle. At the left, a table tipped toward us presents a white vase of yellow-tinged blooms and a light cloth with pale patterns. At the right, a wooden chair receives the sitter, who leans an elbow to the tabletop while crossing one leg over the other. Behind and beneath them spreads the painting’s most commanding element: a single, saturated red that merges wall and floor into one continuous plane. The woman’s torso and the table’s edge create two converging diagonals that meet near her hands and necklace, establishing a visual hinge. From there the gaze can circle clockwise across the face, down the dress, along the crossed legs and shoes, then back up the tablecloth to the flowers. The geometry is legible at a glance—one reason the picture reads immediately from a distance—and yet it contains enough asymmetry to feel alive. Her body tilts ever so slightly toward the viewer; the table is not centered; the chair’s back sneaks into the right edge. Those small imbalances enliven the calm, frontal design.

Color Chords: Blue Against A Climate Of Red

Matisse’s title announces the chromatic drama: a woman in blue placed within a red environment. The blue dress is a cool island, a long vertical that tempers the room’s heat. It is not a single blue but a range—from slate and steel to clouded ultramarine—so that light can move across the folds without resorting to heavy shadow. Around it, the red field behaves like climate rather than backdrop. Brushed in soft, semi-opaque layers, it glows instead of shouting. At crucial points Matisse inserts mediating hues: mustardy stockings that bridge blue and red; a brown-orange chair that ties the figure to the floor; and pale yellows in flowers and tabletop that spark against the warm ground. The small necklace of dark beads provides the lowest value in the palette, anchoring the face in the surrounding warmth. Because all these colors are tuned to the same gentle light, they cooperate rather than compete.

Light As A Continuous Mediterranean Veil

In the Nice years, illumination arrives as a soft, maritime wash. Here it clarifies forms without theatrics. Highlights pool gently along the cheek, forearm, and knee; they do not carve or glitter. Shadows are chromatic, leaning cool within the blue dress and slightly olive along the chair and shoes. Even the red background carries variations—warmer near the table, cooler behind the figure—so the space breathes. This even light allows color to perform the modeling: the dress’s folds are turned by cool-to-cooler transitions, the tablecloth by warm creams sliding toward gray, and the porcelain vase by small temperature shifts that make it luminous without resorting to hard reflections.

The Figure’s Pose: Ease With Inner Architecture

Matisse’s models rarely act; they inhabit. The woman sits with her torso upright, head slightly tilted, and hands calmly gathered near the tabletop. One leg crosses the other, giving the lower half a subtle diagonal that answers the table’s tilt. The pose projects composure, not passivity. It creates a clean set of volumes—the oval of the head, the tapering triangles of forearms, the long block of the dress, and the bent-knee wedge—that Matisse can state with large, readable shapes. The face is simplified to masklike clarity: arched brows, shadowed lids, a small, decisive mouth. This summary is intentional; by reducing facial detail he keeps expression stable within the strong fields of red and blue.

Pattern And Object: Architecture In Disguise

What looks like decoration is the painting’s scaffolding. The patterned tablecloth, with its arabesques and pale embroidery, acts like a soft grid that steadies the left side of the composition. Its lightness keeps the table from becoming a dark block and, at the same time, offers a bridge to the white porcelain vase. The flowers—likely tulips, warmed with yellow and edged by red—set the painting’s highest notes. They are placed slightly above the sitter’s head, so they converse with the face without stealing focus. On the cloth sits a small yellow object, perhaps a compact or book, whose rectangular geometry subtly echoes the tabletop and signals Matisse’s delight in ordinary studio things. All these details provide rhythm and measure, helping the big chords of red and blue find balance.

Drawing Inside The Paint: Lines That Flex And Decide

Matisse draws with the brush, letting contours thicken and thin as they round a form. Along the neckline, a firm dark seam turns the collar; around the forearm, the line breathes, becoming a whisper where color meets color. In the face, a few taut marks—brows, nose wedge, lip shadow—are sufficient to secure likeness and mood. The shoes are simplified to two black lozenges tipped with pale bows; the hands are compact, compressed into essential planes so that gesture, not anatomy, carries meaning. Because drawing is fused to color, the surface never feels outlined or fenced off; it feels discovered.

Space As A Shallow, Intimate Stage

Depth is achieved without linear perspective. The red field sits close to the picture plane, while the table overlaps the dress and the dress overlaps the chair and floor. Value steps down as space recedes—dark bead necklace and hair, mid-value dress, paler tablecloth, brightest vase—so the distance reads clearly. This shallow stage is ideal for the painting’s aims. It keeps attention on relations between fields of color and on the sitter’s presence within a tuned environment, rather than on the illusion of a deep room.

Rhythm, Repetition, And The Eye’s Path

The painting is choreographed for easy circulation. The viewer’s attention lands on the face, descends the vertical of the blue dress, bounces across the mustard stockings to the shoes, slides up the chair leg, and returns via the table’s bright plane to the flowers and back to the face. Repeated shapes keep time: circles of blossoms, necklace beads, and shoe ornaments; soft rectangles of book, table edge, and chair seat; diagonals of forearms and crossed legs echoing the tablecloth’s tilt. Color repeats, too: yellows in flowers, book, and stockings; whites in vase, collar, and tablecloth; small black accents in hair, necklace, and shoes. Each recurrence reassures the eye and binds the parts.

Material Presence And The Pleasure Of Paint

Matisse distinguishes surfaces through touch rather than description. The red field is laid with broad, semi-dry strokes that leave the weave visible, giving the air a tactile grain. The tablecloth shows softer blends and faint scumbles that mimic woven fabric. The vase is smoother, its edges slightly firmer so the porcelain seems to hold light. The dress is painted in longer, slower strokes that drift into one another, suggesting drape and weight. These subtle differences make the scene persuasive without losing the modern cleanliness of large planes.

Psychology Without Anecdote

There is no explicit story, but character emerges. The woman’s poised posture, steady gaze, and neatly composed hands suggest self-possession. The necklace and dress imply care in presentation, while the crossed legs add a note of private ease. The red climate warms the mood, hinting at an interior life full of energy, while the blue dress tempers that heat with reserve. Matisse does not draw drama from expression or gesture; he lets color, scale, and placement carry the emotional weather.

Dialogue With Tradition And With Matisse’s Own Work

“Woman in Blue at a Table, Red Background” converses with portraits by Manet and Ingres that seat figures beside still-life tables, yet it is unmistakably Matisse. Pattern is structural, not ornamental; space is shallow; light is even; drawing breathes within color. Compared with his odalisques of the same years—where pattern multiplies and fabrics luxuriate—this work feels distilled. It is closer to his “harmonies” in a single color family, except that here two primaries, red and blue, are brought into accord by a handful of mediating yellows and whites. The result is both classical in balance and modern in frankness.

Lessons In Design And Looking

The canvas offers enduring lessons. A dominant color field can organize an entire composition if you provide strategic counterweights. Repetition at multiple scales—beads, blossoms, bows—stabilizes complex color. Modeling by temperature rather than by sharp contrast yields volume that feels luminous and humane. Cropping close increases presence, provided internal rhythms keep the eye moving. Finally, ordinary objects—the book, the vase, the patterned cloth—can function as structural devices when placed and tuned with care.

The Viewer’s Time In The Picture

First encounter: a woman in a blue dress beside a pale table in a red room. Second look: a network of gentle oppositions reveals itself—cool to warm, vertical to slanted, rectangle to curve. Third look: micro-events appear—the slight greenish cool along the inside of the forearm, the peach reflection on the stockings cast by the red floor, a feathery revision at the jawline, the thin gray seam that turns the vase’s rim. The painting lengthens time not through narrative but through accumulating relations, rewarding attention with fresh harmonies at each pass.

Conclusion: A Calm Chord Of Figure, Table, And Red Air

“Woman in Blue at a Table, Red Background” condenses Matisse’s Nice-period ideals into a lucid chord. A single figure sits in a tuned climate of red; a blue dress provides the cooling counterweight; flowers, book, and patterned cloth supply rhythm and measure; and a soft, democratic light allows color to carry feeling. Nothing is overstated, yet everything is decided. The portrait’s power lies in how it makes serenity visible—through planes of color, supple contour, and the poised presence of a woman inhabiting her space.