Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

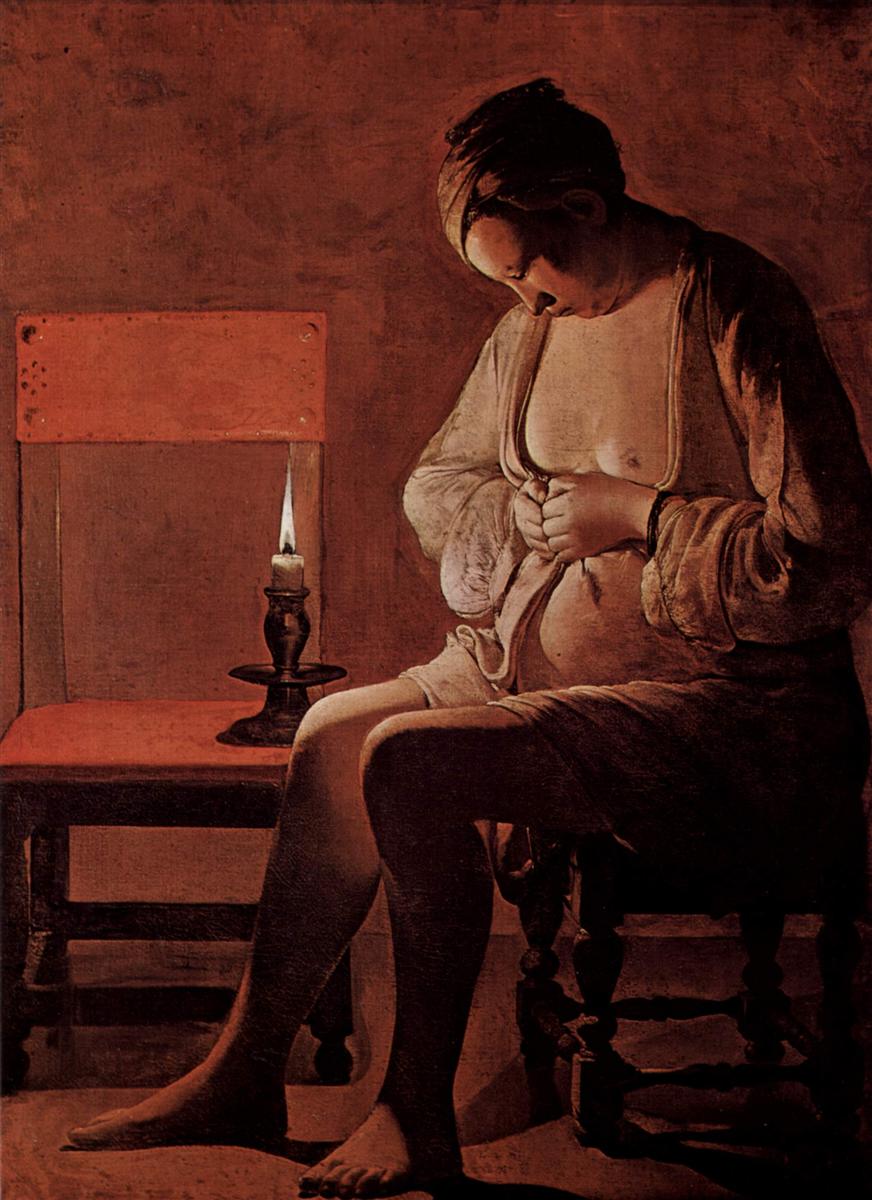

Georges de la Tour’s “Woman Catching a Flea” (1638) turns a moment of private grooming into one of the most piercing nocturnes of the seventeenth century. A young woman sits in a bare room beside a simple chair and a small candlestick. Her garment is loosened; the chemise has slipped, exposing the soft geometry of shoulder and breast. Head bowed, she concentrates on the tiny task of finding and pinching a flea between her fingertips. The scene is quiet to the point of austerity—just two pieces of furniture, a candle, a woman, and a deep field of shadow—yet it opens onto questions about dignity, domesticity, light, and the relationship between attention and grace. With the least dramatic of subjects, de la Tour composes a painting that feels inexhaustibly human.

Composition and the Architecture of Stillness

The canvas is organized around a severe, rectilinear architecture. Two chairs create a measured scaffolding: one occupied, with turned legs and a dark seat; the other empty, reduced to planes of wood and a vertical back rail that catches the candle’s glow. These rectangles frame the figure and keep the eye circulating through the room without escape. The woman’s body supplies the counterpoint. Her head descends in a gentle arc, shoulders rounding forward, torso bending over the lap where both hands gather to their minute labor. The composition pivots on that small knot of fingers at the center right, which quietly becomes the most important point in the picture. Everything else—chair, candle, wall—helps us arrive at that bend in the posture. Stillness is not passive here; it is a structure that supports concentration.

The Candle and the Invention of Moral Weather

De la Tour’s candle is small, with a clean wick and a steady white flame. It sits on a low saucer, just left of the figure, and throws a triangled cone of light across thigh, belly, chest, and cheek. Because the candlestick is close to the empty chair, the light ricochets from wood to wall, turning the emptiness into a reflector. The room’s “weather” becomes a warm, breathable dusk in which textures register without glare. Shadows hold their shape; edges taper rather than vanish. The painter’s single light source does more than describe volume—it governs the mood. It confers fairness on the body, honors the tasks of poverty, and refuses both sentimentality and ridicule. In de la Tour, light is a matter of ethics.

Chiaroscuro Without Spectacle

Though the picture belongs to the Caravaggesque tradition, its chiaroscuro is tempered. De la Tour prefers large, silent planes and slow transitions. The woman’s shoulder is a field of ivory broken by a single slip of shadow along the collarbone; the cheek turns into darkness with a gradient so patient it feels like breath fading. The candle’s highlight on the chair back is one clear stroke; the rest of the wood is all mid-tones, registering use and age. This calm handling trains the viewer’s attention to match the woman’s—unhurried, exact, generous with silence.

Gesture and the Psychology of Attention

The entire narrative lives in the hands. The right hand pinches with thumb and forefinger; the left hand spreads the skin, lifting the fabric of the chemise and guiding the search. The head’s angle confirms the investigative gaze. Nothing is theatrical, and yet the moment has a charged gravity. A flea is almost nothing, but in the logic of the painting it becomes the focal point through which the woman organizes her body and the room arranges its light. De la Tour dignifies attention itself. What the hands do matters less than the fact that they do it with care.

Flesh, Cloth, and the Ethics of Exposure

The loosened garment and exposed breast introduce a vulnerability that could have tempted a painter toward voyeurism. De la Tour chooses another path. Skin is painted with matte fairness and structural respect; it has weight and temperature, not gloss. The chemise is rendered as a working fabric that falls in quiet folds and takes light the way a well-washed linen does, with a soft, granular sheen. The body is neither displayed nor concealed; it is used. The painting’s decency rests in the equality with which skin, cloth, and wood share the same honest light.

Poverty, Furniture, and the Poetics of the Ordinary

There is almost nothing in the room, and what is present is plain. The chairs are not upholstered; the candle is utilitarian; the wall is a scumbled plaster that remembers the day’s heat. This poverty is not shamed. It is arranged with the same pictorial care given to princely interiors in other painters. The empty chair, especially, reads like a quiet metaphor—a partner to the woman’s solitude, a block of color that holds the left half of the composition while also suggesting absence and breath. The painting argues that beauty is a function of attention, not expense.

Symbolism Kept Practical

Seventeenth-century viewers would have recognized moral readings: the flea as a token of sensual distraction or human frailty, the candle as the briefness of life, the empty chair as the place of the absent beloved, the bowed head as humility. De la Tour allows such meanings without insisting on them. He keeps every symbol tethered to use. The flea is also an actual parasite to be removed; the candle a necessary tool; the chair a seat and reflector; the bowed head a posture that better exposes the skin to the hunt. Because symbolism remains practical, the painting avoids sermonizing. It persuades by fidelity to things as they are.

Color Harmony and Emotional Temperature

The palette is limited to a serene chord of warm reds, umbers, and ivory, tuned by the candle’s pale flame. The empty chair contributes a block of brick-red that rhymes with the warmer tones of the woman’s skin and clothing; the wall’s ruddy ground warms the shadows; the candlestick’s dark foot anchors the left side. There is no competitive color to disturb the quiet. The temperature is humane and steady—warm enough to be intimate, cool enough to avoid sentiment. This chromatic restraint is not merely tasteful; it is part of the picture’s moral poise.

The Body’s Geometry and Sculptural Truth

De la Tour builds the figure with sculptor’s logic. The lower leg is a clean cylinder, its top flattened where it meets the edge of the seat; the thigh is a larger drum, turned by a single major highlight and one deep shadow under the knee; the abdomen is a shallow bowl receiving light; the breast is presented without exaggeration as a half-sphere whose lamplight terminator describes volume more than allure. Such clear geometry, combined with the painter’s love of large planes, grants the body a monumental simplicity rare in genre scenes. The woman is not an anecdote; she is form, poise, and agency.

Space, Silence, and the Chamber of Night

The room’s silence is almost audible. De la Tour gives us enough floor to feel the weight of the chair legs, enough wall to let a small echo return from the candle’s flame, enough shadow to breathe. The void is not empty; it is protective. It preserves the privacy of a task conducted at the day’s end when the cooler air invites unhurried attentions. The painter treats that silence as a subject in its own right. Viewers are asked to match it—to look without appetite, to let their own breathing slow to the painting’s metronome.

Manner, Class, and the Nobility of Habit

The subject is working-class; the manner is courtly in its restraint. This tension is part of the painting’s force. De la Tour confers on a poor woman the same clean geometry and judicial light he gives to saints and card players. The implication is clear: dignity attaches not to theme but to treatment; nobility attaches to habit. A person who performs a small task with concentration is already participating in a moral order. The painting does not flatter poverty; it honors effort.

The Candle as Clock

Time is written into the lamp. The stub is short, the wick crisp, the halo contained. We are in the middle of a session, not at the first lighting or the last gutter. The flame’s steadiness suggests a room without draft, a sheltered hour. This temporal precision lends credibility to the posture and intensifies the sense that we witness not a staged moment but a slice of ordinary life. The woman will finish, snuff the candle, and sleep.

Dialogue with De la Tour’s Other Nocturnes

Across de la Tour’s oeuvre, night is a school for looking. In “The Penitent Magdalene,” flame and bone orchestrate a theology of mortality; in “St. Jerome Reading,” light ranks objects in an ethic of study; in “The Newborn,” illumination becomes maternal shelter. “Woman Catching a Flea” belongs to that family but withdraws the explicit allegory. It keeps the single light and large planes, yet moves the drama to the smallest scale—a parasite removed from skin. This descent in subject elevates the theme: attention is the common grace that threads saint and servant, scholar and mother.

Technique, Edge, and Plane as Persuasion

The painting’s authority rests on decisions too calm to announce themselves. De la Tour tightens the edge of the chair seat where the thigh meets wood, so weight feels true. He feathers the shadow at the jaw to prevent the head from cutting out like a silhouette. He gives the candle a few crisp edges—the rim of melted wax, the hard highlight on the saucer—so we trust its brightness. He scumbles thin, warm layers over the wall to catch the light in a granular way that reads as old plaster. The technique hides so that the world can stand forth.

Modern Resonance

The scene reads as startlingly contemporary: a person in a quiet room addressing a small, necessary task by lamplight at day’s end. Substitute the flea with a splinter, a torn seam, or a check on a child’s scalp, and the choreography persists. The painting suggests that the measure of a life is not found in the rarity of its moments but in the quality of attention brought to the ordinary. In an age that rewards spectacle, de la Tour’s canvas feels like a vow: to look closely, to make space, to be exact.

Conclusion

“Woman Catching a Flea” is a masterpiece of restraint that enlarges the moral field of painting. With a handful of truthful things—a chair, a candle, a garment, a body—Georges de la Tour composes an image of attention so focused that it lifts the trivial into the timeless. Composition builds a chamber for stillness; light supplies a fair climate; color keeps the temperature humane; texture grants credibility to every surface; gesture writes the psychology of care. Nothing is wasted. Everything is necessary. By the time our eye returns to the tiny knot of fingers at the picture’s center, we recognize the subject in full: not the flea, but the human capacity to give oneself completely to the task at hand.