Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

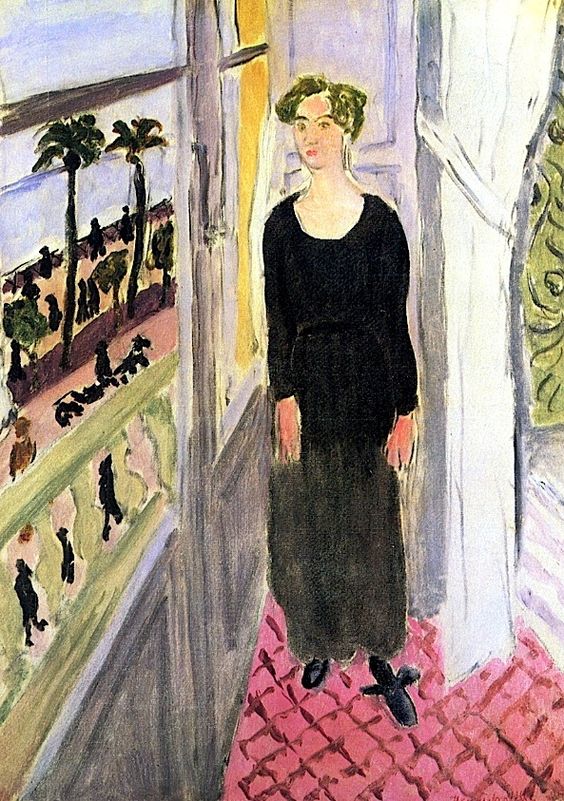

Henri Matisse’s “Woman by the Window” stages a precise meeting between interior calm and exterior motion. A young woman in a dark dress stands on a pink tiled floor, framed by tall shutters and a pale curtain. Through the open window a Mediterranean promenade unspools: palms sway, walkers pass, the sea holds the horizon in a long blue bar. With just a few tuned colors—rose, lavender, sea-blue, and black—Matisse composes a room that breathes and a figure that seems to listen to light. Nothing here is ornamental for its own sake. Every plane, edge, and accent participates in a balanced conversation about looking out and being within.

The Nice Period And A New Classicism

Painted during Matisse’s Nice years, the canvas belongs to a phase when he rebuilt harmony after the turbulent innovations of the 1910s. In these interiors, color turns from blaze to climate, contour becomes a living conductor, and everyday rooms—windows, armchairs, patterned floors—are elevated into laboratories for clear relations. The subject may be simple, but the ambition is exacting: to make a modern classicism in which poise, not spectacle, is the measure of success. “Woman by the Window” exemplifies that ethic, allowing the Mediterranean’s brightness to enter a private space without overwhelming it.

Composition As A Dialogue Of Vertical And Diagonal

The design is anchored by a strong vertical architecture. The jambs of the window, the ghostly panel of the curtain, and the upright figure form a trio of parallel posts that stabilize the scene. Countering them is a diagonal thrust from the tiled floor at lower right toward the open balcony and the strip of sea beyond. These two systems—verticals that reassure, diagonals that invite—generate a subtle tension that keeps the picture awake. The figure stands where they cross, a hinge between room and view. Her position is neither centered nor sidelined; slightly right of center, she grants the window equal claim to the painting’s attention.

The Window As Motif And Mechanism

For Matisse the window is never just an aperture; it is a device for orchestrating space and a metaphor for perception. Here the sash deepens the room with a wedge of cool lavender shadow while the open shutter throws a warm reflection along its edge. The balustrade repeats as a rhythm of pale shapes that march toward the palm-lined promenade. We do not step outdoors—the surface remains a painting, not a theatrical set—but our eye travels outward along the balcony, then returns to the figure, then goes out again. The window thus becomes a pump that circulates attention between inside and outside.

Color Climate: Rose, Lavender, Sea, And Black

The palette is spare, almost musical. The pink floor provides a warm ground note, lifted by the lattice pattern that prevents it from reading as a flat swath. The walls and woodwork hover in pearly lavenders and cool grays, creating a reservoir of air. Beyond the balustrade a narrow band of turquoise-blue water and pale sky refreshes the chord. Against this climate the black dress is crucial: it gathers the room’s values, giving the composition a center of gravity. Yet Matisse tempers the black with surrounding light so it never feels heavy. The face and hands—warm peach touched with rose—mediate between garment and room, holding the human scale.

Light Distributed Rather Than Spotlit

There is no single directional beam. Light here is a network of relationships: the floor tiles brighten as they approach the window; the curtain carries a cool luster; the wall panels soften into lavender; the woman’s dress drinks light in deep breaths rather than reflecting it in theatrical shine. Highlights are small but decisive—the glint on a shoe bow, a pale edge along the profile, a sunlit strip across the sash. Because the picture avoids high and low extremes, the whole feels evenly illuminated, like daylight filtered through fabric.

Pattern As Structure

Matisse lets pattern do quiet engineering. The floor’s pink grid tilts the space without pedantic perspective and supplies a tempo that echoes the promenade’s steady movement. The balcony balusters create a second pattern—a run of bright cutouts that separate room from view while keeping them in rhythm. Even the foliage of the palms, simplified into dark tufts, behaves like small beats in a long measure. Pattern is not decoration; it is the architecture of time inside the picture.

The Figure As Poised Intermediary

The woman’s posture is calm and alert. Her arms hang easily; her feet plant securely in their ribboned shoes; her head turns just enough to engage the outdoors without abandoning the room. The face is summarized with a handful of marks, enough to register presence but not to impose psychology. What matters is her function in the composition: she translates outside light into inside poise. The black dress, falling as a single large shape with soft inflections, makes her legible at a distance; up close, small shifts in value along the waist and hem reveal the body beneath. She is neither mannequin nor anecdote—she is the axis.

Space Held Close To The Surface

Depth is constructed through overlap and tuned value rather than through a hard vanishing point. The floor tilts up; the sash overlaps the woman; the balcony rails overlap the promenade; and beyond them the sea runs like an unbroken sentence. This construction keeps the viewer aware of the canvas even as the eye enjoys the suggestion of space. Modern clarity and pictorial illusion coexist without quarrel.

Brushwork And The Evidence Of Decisions

The surface wears its making openly. The floor lattice is drawn with brisk, confident strokes that thin and thicken as the hand moves away from the artist’s body. The curtain is laid in translucent passes that allow the undercolor to shimmer through like gauze. The promenade figures are signed in with a few dark commas and crescents—enough to read as walkers and dogs but never enough to become narrative distractions. The face is touched lightly; the dress is painted more broadly, its blacks interleaved with grays to prevent deadness. Everywhere the brush stops as soon as the form reads, conserving freshness.

The Outside World As Frieze

The promenade is treated like a frieze running across the window’s aperture. Palms rise at regular intervals; small silhouettes pass left and right; the sea stabilizes the horizon. This distance is important. It keeps the outside from becoming a competing subject and lets the inside remain the painting’s true home. Yet the frieze carries a hum of life that enriches the room—a reminder that calm indoors can coexist with motion outdoors.

Movement Of The Eye

The composition proposes a dependable circuit. Most viewers begin at the face, drop along the black dress to the shoe bows, cross the pink grid to the balcony, follow the balusters outward to the palms and sea, and then travel up the curtain to return along the lavender sash to the face. Each lap yields further pleasures: a faint yellow glimmer just beyond the jamb, a cool seam in the curtain fold, a slightly warmer note on the cheek, a shadow that pools around the hem like a soft echo. The painting invites this looping; it is built for revisits.

Comparisons With Sister Works

Many Nice-period interiors feature open windows, striped floors, and figures in quiet poses. Compared with “Woman By The Window” from the same year that includes more furniture, this canvas is stripped to essentials: no heavy armchair, no table, only the figure, the aperture, and the floor. The reduction increases the clarity of the theme—mediation between interior and exterior—and lets the black dress act as a fulcrum. Where earlier Fauvist works roared in raw chroma, this painting finds intensity in proportion and placement.

The Black Dress And Its Meanings

The choice of black is strategic and humane. It bestows gravity on the figure, ensuring she will not be outshone by the view. It lets the warm skin read clearly, and it speaks to modern dress—simple, practical, elegant without ornament. Black here is not mourning; it is measure. Matisse uses the hue as a complete color, full of nuance where it meets light, and as a structural anchor that lets pinks, lavenders, and blues vibrate without chaos.

Sensation Over Description

What the painting transmits is not a catalogue of objects but a set of sensations: the coolness of tile underfoot, the thin breath of sea air entering an interior, the soft drag of daylight along a dark sleeve, the slow procession of silhouettes below. These arrive through right relations—warm beside cool, dark alongside pale, hard linear grid against soft curtain—not through descriptive trivia. The viewer feels the scene more than they read it.

The Ethics Of Calm

Matisse’s Nice interiors advance a quiet ethic: rooms should be arranged to receive attention and rest. The window welcomes distance without abandoning intimacy; the colors release stress; the composition gives the body of the viewer a path to travel that never jars. “Woman by the Window” makes calm active, not inert. It reminds us that poise is a way of being in the world, and that art can rehearse it.

Why The Image Endures

The picture remains memorable because its parts seem inevitable once seen: the pink grid that makes space walkable; the lavender wall that keeps light breathable; the frieze of palms that sets a distant tempo; the black dress that grounds everything and makes the human measure unmistakable. You can return to it and find the same steadiness gathering you up. It is, like a well-composed sentence, something the mind likes to keep around.

Conclusion

“Woman by the Window” is a chamber piece in paint: a few instruments—floor, window, figure, sea—tuned to the same key and played with even, supple tone. The canvas offers no melodrama, only a rightness of relation in which inside and outside trade breath. Matisse’s line conducts, his colors set the air, and his figure stands where worlds meet, neither absorbed by the view nor sealed away from it. The painting’s gift is a felt equilibrium, effortlessly modern and calmly radiant.