Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

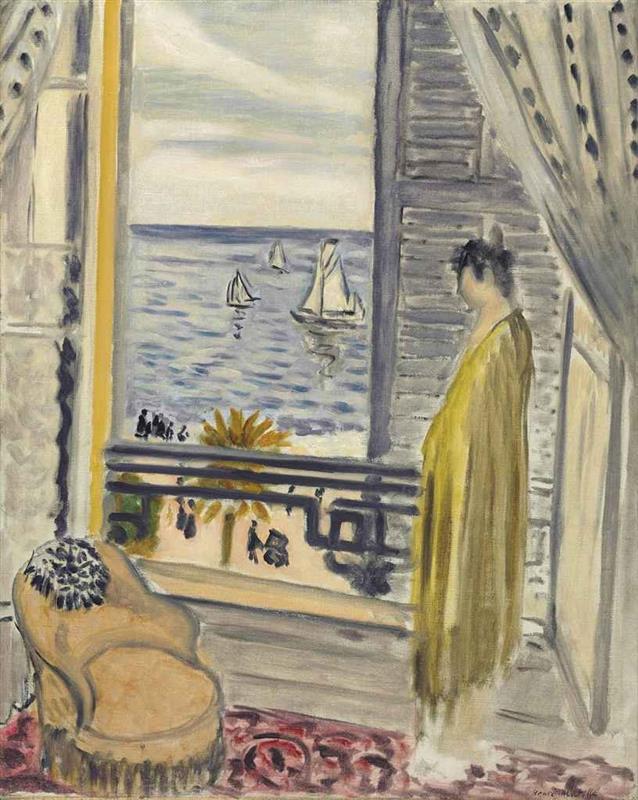

Henri Matisse’s “Woman by the Window” (1920) turns a quiet room into a stage where interior poise and exterior light meet. A figure in a pale yellow robe stands near a tall opening, shutters folded back, curtains drawn aside, sea and sails bright beyond the balustrade. An armchair waits in the foreground on a red, arabesque carpet. Nothing here clamors for attention, yet the parts hum together: the window frames the day; the day pours in to color the room; and the woman, half-absorbed in the view, binds the two worlds. The painting offers not a dramatic narrative but the refined pleasure of a threshold—the moment when looking outward and dwelling inward become one act.

The Nice Period And The Return To Calm

Created at the dawn of the 1920s, the canvas belongs to Matisse’s early Nice period, a time marked by clarity, light, and a modern classicism tempered by domestic comfort. After the upheavals of the previous decade, he gravitated toward interiors that opened to terraces and water, spaces where patterned carpets, soft chairs, shutters, and curtains supplied a grammar of rhythm while the Mediterranean provided measured luminosity. “Woman by the Window” exemplifies this search for serenity without dullness. Instead of the blazing color shocks of Fauvism, he uses measured intervals of blue, pearl gray, straw yellow, and rose to build an atmosphere the eye can inhabit.

The Open Window As Structural Device

For Matisse, the open window is not only a subject; it is a thinking tool. It creates a frame within the frame and stages the act of looking. In this painting the window splits the composition into nested rectangles: the room’s interior forms the first, the shuttered opening the second, and the exterior sea view a third. This stacking clarifies space while inviting the viewer to move through it. The railing and the slab of balcony compress the passage between in and out, so the sea feels close and the room remains permeable. The motif also echoes the very nature of a painting—an opening onto a world that is fundamentally a flat surface—making the image a quiet meditation on representation itself.

Composition And The Architecture Of Balance

Matisse constructs balance from a few decisive axes. A tall, vertical shutter steadies the right side; a matching upright—curtain and jamb—answers at left. Between them the sea is a horizontal plane that anchors the middle distance. Diagonals from the balustrade and from the overlapping carpet motifs push the gaze toward the window and out across the water. The figure stands to the right, her robe descending in a soft column that counters the horizontal sea and the circular arabesques of the carpet. The armchair’s oval back and the sunflower-like shape on the balcony introduce rounded forms that prevent the composition from stiffening. The result is an architecture of curves and bands within which the eye travels unhurriedly.

Color And The Temperature Of The Room

The palette is tempered, lucid, and coastal. The sea is phrased in cool blues and silvery strokes; the sky is a pale, quiet band mottled with light. The room takes on those tones—pearl grays in shutter and wall, a chalky white in the curtains, violet shadows on the floor—so that interior and exterior converse. Against this cool climate, Matisse places warm notes to keep the space human: the robe’s straw yellow, the armchair’s honeyed upholstery, and the coral swirls of the carpet. These warm accents do not compete with the blues; they share the air with them. Color is not spectacle here; it is weather—gentle, breathable, and steady.

Light As The Silent Protagonist

Light behaves like a calm intelligence spread across the canvas. It calibrates rather than dazzles. Outside, small reflections flicker beside the sails; inside, value shifts keep the shutter legible without heaviness and sketch the folds of the robe without theatrics. Curtains do not blaze; they diffuse. The figure is illuminated not by spotlight but by the room’s accumulated radiance. Even the carpet’s reds are moderated by veils of gray so they belong to the same atmosphere. The painting records light as a lived condition, the kind that sustains attention rather than seizes it.

The Figure’s Gesture And Psychological Register

The woman’s posture is contemplative and unperformed. She faces the window, head gently inclined, hands together near her waist. We sense a pause rather than a pose—someone listening to the day, perhaps counting sails, perhaps simply resting in the present. The robe’s vertical fall reinforces this inwardness; it is a garment of ease, not display. Matisse avoids facial detail because he is after a climate of mind: privacy within openness, absorption within light. In giving us the figure at an angle, he invites us to share her view rather than to interrogate her expression. The result is a respectful proximity, a humane way of looking.

Furniture, Carpet, And The Ethics Of Comfort

The armchair and carpet are not decorative afterthoughts; they carry meaning and structure. The chair’s rounded back repeats the window’s arch and offers a place for the body to settle, as if the room were designed around the idea of repose. Its warm upholstery and the darker floral tuft on the cushion introduce tactile notes that anchor the composition’s lower left. The carpet, with its red arabesques, supplies tempo to the floor and counterbalances the room’s coolness. Together, chair and carpet transform the interior into a hospitable environment—a modern luxury measured not by opulence but by the rightness of color, light, and seating.

The Sea View And The Notation Of Distance

Beyond the balustrade, a procession of sails moves across the water. Matisse resists the urge to model hulls or rigging; he uses abbreviated shapes and quick reflections to write “sailboat” in a painter’s shorthand. These distant forms, reduced but vivid, pull the eye into depth without breaking the painting’s calm. The horizon line is high enough to expand the blue field yet low enough to keep the room dominant. The exterior is real, but it belongs to the painting’s order. Distance is not a threat to intimacy; it is its extension.

Space, Depth, And The Pace Of Looking

Depth arrives through a sequence of gentle thresholds. The viewer begins in the foreground with the chair and carpet; crosses the bright rectangle of the floor; pauses at the balustrade; and then glides out onto the sea. The shutter, half-closed, and the curtain, half-parted, register this movement with soft vertical beats. Nothing is abrupt. The eye’s passage is paced like a walk through a well-proportioned room: measured steps, small adjustments, and then an opening to air. Because the path is clear, the viewer returns easily to the figure and begins the loop again. The painting is built for repeated circuits rather than a single revelation.

Drawing, Contour, And The Living Line

Matisse’s contour—dark, elastic, and sparingly applied—provides the image with clarity. It firms around the chair’s silhouette, floats along the robe’s edge, and strengthens the balustrade’s geometry. In the sea and sky the line withdraws, letting strokes and value define form. This alternation keeps the picture poised between graphic decisiveness and painterly softness. Where architectural edges risk rigidity, the line is softened by scumbled paint; where fabric risks dissolving, the line steadies it. The contour behaves like a pulse through the image, a subtle conductor ensuring that every part plays in the same key.

Brushwork And The Evidence Of Making

The surface preserves the movement of the hand. Sea and sky are layered with lateral strokes that admit the ground, giving the sensation of moving air and water. The carpet’s red motifs are brushed in with loaded paint that thins at the edges, so their energy is felt without counting every loop. Curtains and shutters bear dry drags and wet merges, signs of decisions made in time rather than polished away. This candor is central to the work’s charm: viewers sense the painter in the room with them, adjusting, balancing, clarifying.

Rhythm And The Music Of The Room

The painting’s pleasure lies partly in its rhythm—the way repeated forms create a calm beat. Vertical shutter, vertical curtain, vertical robe; horizontal balcony, horizontal horizon, horizontal floor stripes; circular chair back and carpet whorls. These repetitions bind interior and exterior into one measured cadence. Even the sails participate as small triangles at regular intervals. Rhythm here is not decoration; it is the logic that makes a room feel inhabitable.

Thresholds, Leisure, And The Modern Sensibility

Matisse often treats leisure as an ethical subject: the right to rest, to look, to breathe at one’s own pace. “Woman by the Window” is an image of such leisure. Not ostentatious vacation, but daily gentleness—curtains drawn to admit light, a chair placed for comfort, a moment spared to follow boats along the horizon. The open window stands for permeability between life and world; it implies hospitality. In a postwar context, this domestic ease becomes quietly momentous. The painting proposes that clarity, balance, and comfort are worthy artistic values.

Dialogues With Sister Works

The canvas converses with Matisse’s earlier open-window pictures and his Nice interiors. Compared with the blazing 1905 “Open Window,” this painting softens chroma in favor of measured tonality. Compared with his odalisque rooms of the later 1920s, it is less decorative but equally architectural; the arabesque carpet plays the role that patterned screens and textiles will soon amplify. The figure at the window echoes many of his seated or standing women whose identities are shaped as much by the rooms they inhabit as by facial features. The continuity is clear: a vocabulary of frames, bands, and arabesques held in harmonic proportion.

The Viewer’s Path Through The Image

The picture invites a reliable circuit. The eye often starts on the chair’s warm oval, glides across the carpet and floor to the balustrade, slips out to the boats, traces the horizon, and returns by the right shutter to the figure’s face and robe before dropping again to the carpet. Each return reveals small felicities—a darker seam in the shutter slats, a quick gray inside a sail, a softened edge where robe meets wall. The painting rewards time by making looking itself the subject.

Material Presence And The Beauty Of Restraint

Despite its richness, the painting is not heavy. Paint is distributed with restraint: thin in the shutters, airy in the curtains, denser at the carpet motifs, delicate in the boats. The room’s forms are large and legible; there is no compulsion to polish or to enumerate. This economy lets the surface breathe and keeps the mood lucid. The viewer senses a harmony achieved not by accumulation, but by exact choice.

Meaning Without Program

The scene admits many readings—contemplation, anticipation, daydream—but it avoids programmatic symbolism. Matisse trusts the ordinary to carry depth. A woman stands by a window; a day opens beyond; the room holds. In that triad lies an affirmation of continuity. The painting argues, without rhetoric, that everyday arrangements of light and space can sustain the spirit.

Conclusion

“Woman by the Window” translates a modest domestic moment into a precise and generous orchestration of line, color, and light. The figure’s quiet stance, the window’s nested frames, the sea’s measured blue, the chair’s warm oval, and the carpet’s soft pulse together create a climate the eye wants to live in. Nothing here is forced, yet nothing is casual. Matisse composes the experience of a threshold so clearly that it becomes a lasting form: a room that opens to the world and a world that returns brightness to the room. In that balanced exchange, the painting offers a durable promise of calm.