Image source: artvee.com

First Glance: A Quiet Explosion of Line

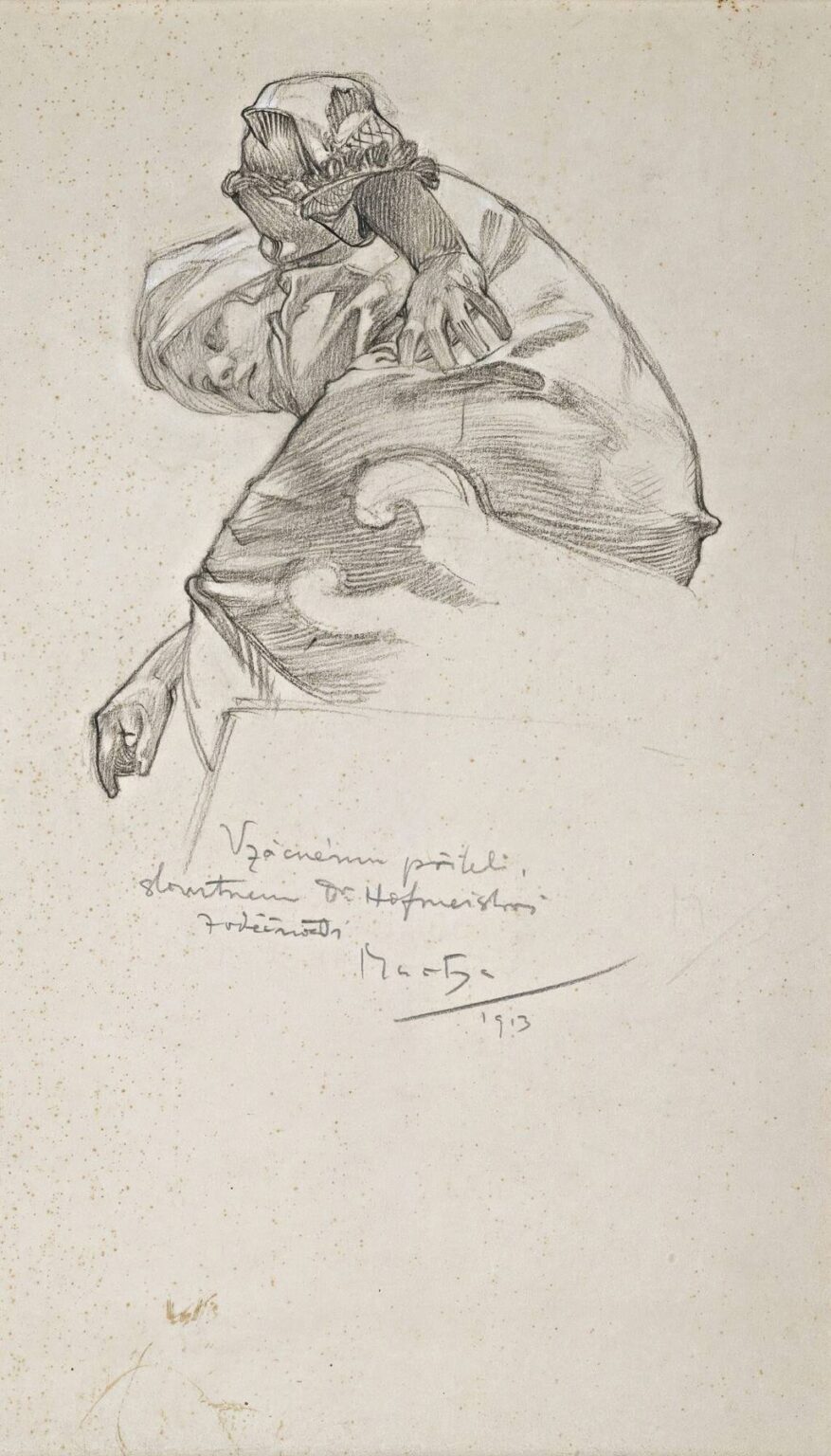

At first encounter, “Woman Bending Over” looks disarmingly slight: a compact cluster of graphite marks occupies the upper left of a large, nearly empty sheet. Step closer and the drawing swells in complexity. A woman in a kerchief and ruffled cuff leans forward over a rounded form, one forearm thrust diagonally across the page, the other arm dropping with a relaxed hand. Drapery rolls in broad, wave-like folds; shadows gather and dissipate in delicate hatching; a quick Czech inscription and the date 1913 sit below. There is no background, no stage, no explanatory props. Everything—gesture, weight, time—must be gleaned from the way pencil meets paper. The spareness is a challenge and a gift. Mucha asks us to look as he did, to see movement and intention in the grain of a line.

The Subject and Its Ambiguity

What exactly is the woman doing? The title names the action without fixing the narrative. She could be tucking a child into bed, setting down a heavy bundle, reaching across a table, or adjusting cloth on a chair. Mucha avoids the anecdotal in favor of kinetics: a body hinged at the waist, shoulder rotating, head turning away, weight caught mid-transfer. The ambiguity matters. Because we are not distracted by a story, we study the architecture of motion—how the drapery confirms the bend, how the cuff compresses, how the hand relaxes once the task is nearly done. The drawing becomes a diagram of lived motion more than an illustration of any one event.

Composition: A Poised Off-Balance

The image is cunningly placed. Most of the activity crowds the upper left quadrant. A sweeping contour arcs from the upper right toward the lower left, describing the bulging cloth that covers the woman’s back and shoulder. This strong curve is countered by the descending diagonal of the forearm and the small, pendulous hand near the lower left edge. The resulting geometry is a poised off-balance that keeps the eye traveling in loops: up the forearm, across the cuff, over the shoulder’s swelling drapery, back down to the limp hand, and up again. The generous vacuum of paper to the right and below is not emptiness but tension, a field into which the figure seems to lean. By concentrating form into a corner, Mucha turns blankness into force.

The Language of Drapery

Mucha is a virtuoso of cloth. Here the drapery is not a passive covering; it is the instrument through which movement becomes visible. Over the shoulder, large S-curves roll like surf, their crests picked out by firm edges, their troughs softened by even hatching. At the cuff, the fabric pinches and bunches, the pencil describing not only light but also pressure—we feel the garment squeezing the wrist as the arm bears weight. Along the upper arm, short, parallel striations bend with the anatomy beneath, making the sleeve read as fabric clinging to form rather than a general mass. This disciplined description prevents the arabesques from drifting into decorative abstraction. They are pretty, yes, but their prettiness is earned by physics.

Anatomy Through Cloth

Even though bare skin appears only at the face and hand, the body’s structure is everywhere. The shoulder joint is convincingly placed under the bulge of cloth; the deltoid’s turn explains the orientation of the sleeve’s stripes; the forearm’s pronation is clear where the cuff wraps and the hand angles downward. Mucha builds a credible skeleton and lets fabric reveal it. This ability—anatomy without nakedness—helps explain why his poster women, swaddled in robes and jewels, still feel alive. Here, the convincing bent torso holds the entire composition together without the need for contour lines around the waist or hips.

The Face as a Resting Rhythm

Peering out from the left edge is a small face tilted down, half nestled in cloth, half turned away. The features are economical: a soft contour for the nose, a shadow for the upper lid, a hint of mouth. Even in this minimal state, the face supplies the drawing’s human temperature. It also contributes rhythm. The downward tilt of the head repeats, at smaller scale, the downward tilt of the forearm and the hanging hand. These echoing angles knit the composition, moving the eye from micro gesture to macro arc.

Hands: The Truth-Tellers

Mucha’s hands are never afterthoughts. The slack left hand at the lower edge, fingers relaxed and slightly curled, tells us the task is either done or nearly done; the hand releases because the shoulder and forearm are carrying the remaining load. The right hand—emerging at the end of the diagonal forearm near the center—bears signs of grip and intent. The thumb clings, the cuff squeezes, the tendons twitch beneath cross-hatching. With very little, Mucha conveys both the distribution of weight and the psychology of effort. These hands could belong to a peasant arranging household cloth or to a goddess rearranging clouds; their truth lies in how they respond to force.

The Pencil’s Voice

Graphite’s flexibility is on full display. Mucha deploys several distinct strokes: long, sweeping contours that define large forms; short parallel hatching that lays down half-tones; hockey-stick hatching—short arcs repeated along a path—to describe rounded planes; and delicate, nearly powdery shading where fabric turns into shadow. The lines thicken at stress points—the compressed cuff, the edge of a fold, the outline of the hand—and thin where forms release into light. This pressure choreography turns drawing into music; we can almost hear where the pencil presses and where it lifts. A few crisp accents, like the dark notch under the cuff or the thin crease along the back, act as percussive beats that keep the visual tempo.

Negative Space as Breath

Most of the paper remains unmarked, speckled only with age spots. That negative space is not an afterthought. It is breathing room that amplifies the realism of the drawn forms. Because nothing competes with the figure, our perception of light becomes ambient—an entire blank world surrounds the woman, as if she were working in a large, quiet room. The emptiness also sharpens the sense of immediacy: we catch a single, unguarded moment before it dissolves into the next movement. In his famous posters, Mucha used frames, halos and text to organize space. Here he uses silence.

The Inscription and the Social Life of the Sheet

Below the figure lies a handwritten dedication in Czech, followed by the artist’s signature and date. The inscription anchors the sheet in lived relationships—likely a gift or a token of thanks. It reminds us that drawings circulated among friends, patrons and collaborators as private communications. The text’s flowing rhythm echoes the curves above; word and image belong to the same hand. In a period when Mucha could command printing presses and billboards, the intimacy of this signed message suggests a parallel life of small, personal works.

1913: Between Epic and Portrait

The date places the drawing in the years when Mucha was deeply engaged with national themes and when preparatory work for large historical projects occupied his attention. “Woman Bending Over” feels like counterpoint to that public labor. Its scale is modest, its subject domestic, its medium immediate. Yet the same artistic convictions appear: the dignity of ordinary gesture, the belief that line can carry meaning without spectacle, and the persistence of Slavic visual memory in the kerchief, the cuff, the peasant-like clothing. The year before the convulsions of the First World War lends the sheet a quiet poignancy—a pause before history accelerates.

Connections to the Art Nouveau Line

Mucha’s name is inseparable from the whiplash curve of Art Nouveau. This drawing shows how that famous line remains rooted in observation. The big arabesque across the back is not a decorative flourish pasted onto anatomy; it is the natural path of stretched cloth over a bent torso. When later he enlarged such curves into poster borders or architectural ornaments, he was not abandoning realism; he was generalizing it—turning truths of body and fabric into a visual syntax. “Woman Bending Over” is a grammar lesson in that syntax.

Gesture, Time, and the Snapshot Effect

The drawing captures a single frame in a sequence. The sluggish hand, the strained forearm and the compressed cuff imply what came before (a lift, a reach) and what will come after (release, relaxation). Mucha hints at duration without resorting to motion blur or repetitions of pose. His method is to embed temporal suggestions inside static details: the way a fold lags behind the arm that moved; the way a hand remembers the weight it just held. This is as close as pencil gets to film.

The Poetics of Incompletion

Only part of the figure is present; the lower body is missing; the support the woman leans on is barely outlined. Rather than a deficiency, this incompletion functions as poetry. It invites the viewer’s collaboration. We supply the hidden hips, the unseen feet, the rest of the table or bed. Our imagined additions must conform to the clues Mucha gives—the angle of the arm, the downward pull of cloth—so the act of looking becomes co-creation governed by evidence. That participation is one reason the drawing feels intimate. We are not just spectators; we help finish the gesture.

Psychological Temperature

What mood inhabits the scene? The tilted head, partially hidden in cloth, reads as focused rather than weary. The hands are purposeful; the drapery is alive with energy; the forms are firm, not drooping. The drawing conveys absorbed attention, that human state in which the self recedes and the task fills consciousness. One senses the sitter is not aware of being observed, or else trusts the observer enough to keep working. Mucha’s empathy for such states—reading, weaving, arranging, playing—pervades his oeuvre. He is less interested in spectacular emotion than in the everyday nobility of concentration.

Lessons in Drawing from Life

For students of draftsmanship, the sheet is a compact tutorial. It demonstrates how to anchor a pose with a few decisive contours; how to model cloth by mixing parallel hatching with directional curves; how to vary edge quality to suggest depth; how to use the page’s emptiness to produce atmosphere; how to let one or two truthful hands carry more expression than a fully described face. It also instructs in restraint: stopping when the statement is complete, leaving room for silence.

Material Presence and Conservation

The paper’s faint foxing freckles and the softness of the graphite are part of the drawing’s charm. They record time without compromising legibility. One can imagine the pencil’s drag across the sheet, the occasional lift, the erasure of a probing stroke. Mucha’s surfaces are generally unfussy; he trusted the clarity of first intentions. That trust yields a tactile presence, as if the energy of the studio session still hangs about the sheet.

Echoes of Domestic and Folk Life

The headscarf, the gathered sleeve, the sturdy cloth suggest vernacular dress rather than theatrical costume. They point to the everyday world that fed Mucha’s imagination: kitchens, workshops, village rituals. The artist’s nationalism was not abstract; it was grounded in textures, tools and gestures repeated across generations. Even within cosmopolitan Paris and Prague, he carried these formative images. Here they appear without rhetoric, simply because they belong to the life of a woman bending to work.

Why the Drawing Feels Contemporary

Despite the period costume, the sheet reads as modern. Its radical cropping, open field, and focus on partial information anticipate later design and photography. The absence of decorative borders and the reliance on gesture align it with twentieth-century graphic minimalism. Above all, its ethics of attention—the choice to honor a small moment with great care—answers contemporary desires for images that feel honest and unforced.

Placing the Work Within Mucha’s Legacy

Viewers often know Mucha through bright posters and ornate cycles. “Woman Bending Over” expands that picture. It reveals the patient observer behind the virtuoso designer, the craftsman for whom a turned wrist could carry as much meaning as a halo of flowers. It also shows the continuity between the intimate and the monumental in his practice. The same mind that organized murals could find structure in a single arm and make a world of it.

Conclusion: The Grace of the Unseen

“Woman Bending Over” is a drawing about work, privacy and grace. It gives no stage, no narrative, no ornament to lean on. Instead, it trusts the viewer to recognize the rightness of a body in motion and to find beauty in the honesty of a task. The curve across the back, the compression at the cuff, the relaxed hand at the edge—all are precise, compassionate notes in a short score played on graphite. In 1913, on a quiet sheet, Alphonse Mucha composed a hymn to attention, and the music still carries.