Image source:wikiart.org

Introduction

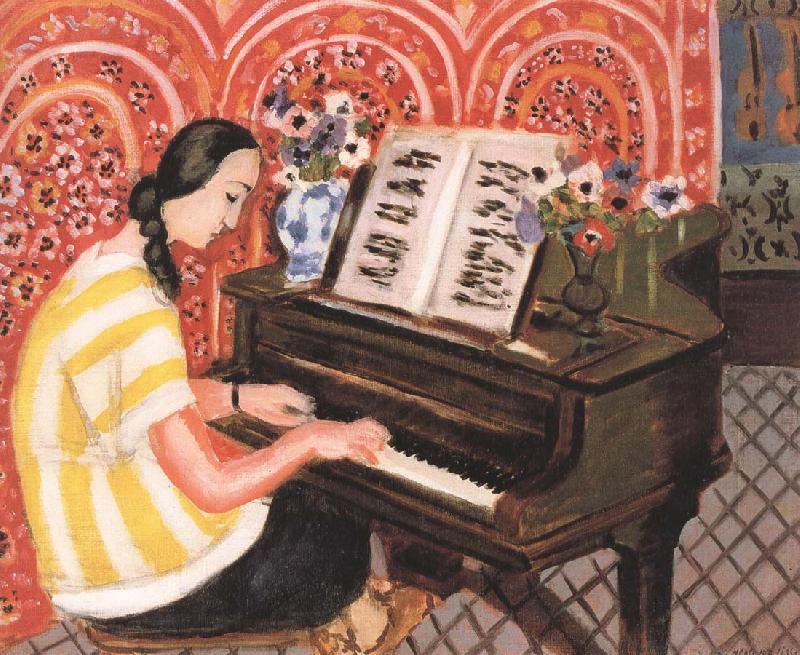

Henri Matisse’s “Woman at the Piano” (1925) is a compact manifesto of the Nice period, where music, pattern, and domestic calm converge into a single, buoyant image. The scene is simple: a young woman in a yellow-striped blouse plays a piano set against a coral red wall patterned with arches and blossoms. Open sheet music, cut flowers in vases, a tiled floor, and a painted frieze of instruments complete the room. Yet beneath this modest subject runs a complex orchestration of color and rhythm. The picture does not merely show a person making music; it paints music, translating meter and melody into intervals of hue, contour, and repeating motif. The result is an interior that feels both intimate and theatrical, as if the room itself were a resonant instrument.

The Nice Period and the Turn to Harmony

By the mid-1920s Matisse had settled into a Mediterranean routine that replaced the violent contrasts of early Fauvism with a poised, decorative language. In Nice he sought an art that could be, as he famously put it, a calming influence. Interiors provided the ideal laboratory: controllable light, movable props, patterned textiles, and models at ease. “Woman at the Piano” epitomizes this phase. Its comforts are deliberate rather than sentimental. The red, yellow, and green chords are tuned to sit in equilibrium; contours are decisive but gentle; and the entire surface is treated as a coordinated field rather than an illusionistic room. It is a picture about pleasure, but pleasure achieved through measure.

Musical Subject, Pictorial Music

Choosing a pianist as subject is not incidental. Matisse had long compared painting to music, and here the analogy becomes literal and structural. The keyboard establishes a band of small repeating units that rhyme with the blossoms on the wall and the tiles on the floor. The woman’s hands, poised above the keys, become punctuation marks in the visual score. Even the striped blouse behaves like a metronome, each yellow band a steady beat running down the figure’s torso and arm. The wallpaper’s great red arches rise like swelling phrases, while the sheet music forms a central, open diptych that reads as two white measures bordered by the dark piano case. Every element participates in a larger rhythm that you do not hear but see.

Composition and the Choreography of Attention

The composition organizes the rectangle like a stage set, with the piano angled diagonally from lower right toward the center, guiding the eye to the performer and the notation she reads. The woman’s bowed head keeps the space intimate, drawing the viewer into the private world of practice rather than spectacle. The flowers flank the score as if they were decorative speakers broadcasting scent and color. At the far right a narrow vertical band of blue-green wall with painted instruments counterbalances the red expanse, preventing the composition from tipping. The floor tiles, receding modestly, keep a sense of place without demanding realistic perspective. Everything is choreographed so that the eye moves across the picture at the tempo of a slow étude—steady, attentive, unhurried.

Color as Key and Modulation

Color carries the emotional tone. The dominant coral red of the wall establishes warmth and fullness, but Matisse cools and stabilizes it with greens in the piano’s reflecting lid, in the foliage of the bouquets, and in the frieze to the right. Yellow enters as a distinct voice, bright but creamy, through the stripes of the blouse and the scattered flower centers. Blue, concentrated in a single ceramic vase and in faint notations on the music leaves, provides a refreshing counterpoint that prevents the palette from overheating. The black of the piano is not a void; it is a deep, lustrous field that absorbs surrounding colors and returns them softened. The whole palette functions like a well-tuned chord in which no note dominates for long.

Pattern as Structure Rather Than Ornament

The Nice pictures are celebrated for their patterns, and this canvas shows why. Pattern here is not decorative frosting; it is structure. The wall’s repeating arches organize the background into measured bays, like musical bars. Their internal blossoms echo the bouquets and create a conversation between real flowers and painted ones. The blouse’s stripes discipline the figure’s volume, converting the curve of a shoulder or forearm into legible, rhythmic shape. The tiled floor, drawn as a lattice of diamonds, provides a quiet grid that steadies the exuberant wall. Pattern flattens space just enough to assert the painting’s surface while allowing objects to remain recognizable. The eye toggles between reading pattern as fabric or wall and reading it as abstract interval, which keeps the image lively.

Drawing, Contour, and the Soft Authority of Line

Matisse’s drawing is spare and confident. The woman’s profile is described with a few soft strokes that give her an inward, listening poise. The arm and wrist are defined by supple contours that suggest weight and motion without resorting to modeling. Even the piano’s heavy case is built from elegant lines, the corners rounded so the instrument participates in the painting’s overall tenderness rather than resisting it. Line here acts like phrasing in music: it shapes passages, introduces pauses, and modulates intensity. Because the lines are never brittle or overbearing, the picture retains a human tempo, as if it had been drawn in time with the music being played.

The Pictorial Role of the Piano

Most representations of pianos risk turning them into black rectangles that swallow light. Matisse solves this by giving the instrument a green sheen and by letting its planes pick up nearby colors. The slanted top acts as a reflector for flowers and wall; the narrow keyboard band becomes a bright horizontal accent; and the music stand introduces a vertical hinge at the center of the composition. The piano is thus both object and stage. It grounds the scene with weight while also distributing color and rhythm throughout the picture.

Flowers as Color Voices

The bouquets are small but decisive. They tether the open score to the room and punctuate the field of red with cool and warm notes. Matisse paints them with brisk, rounded touches that rhyme with the small floral dots on the wall. They are not botanical studies; they are color voices—violet, white, red, dark green—clustered to balance the large fields of red, black, and yellow. Their placement to either side of the music creates a triptych of sorts, with flowers as wings and notation as the central panel.

Interior Space and Productive Flatness

The room is recognizable, but its depth is kept shallow. The piano advances toward us, the wall presses gently forward, and the floor rises just enough to anchor the legs of the instrument. This controlled compression focuses attention on surface relationships rather than on recession. Matisse does not deny space; he edits it. The effect is like listening to chamber music rather than a symphony: intimacy over grandeur, clarity over echoing depth. The interior becomes a place of attention where color and line can operate without theatrical distraction.

Gesture, Process, and the Material of Paint

Despite the surface’s careful order, the paint handling remains fresh and evident. The wall’s red is laid in with visible strokes that slightly vary in saturation, allowing the pattern to feel breathed into the field rather than pasted on top. The blouse’s yellow stripes have the directness of a single pass with a loaded brush. The piano’s dark planes are scumbled with green and brown, avoiding dead flatness. These traces of process ensure that the picture remains alive to the act of making, which dovetails with the subject of practicing music. Painting and playing become parallel crafts, both based on repetition, refinement, and the control of tempo.

A Dialogue with “The Piano Lesson”

This 1925 interior resonates against Matisse’s earlier “The Piano Lesson” (1916), an austere, gray-green composition where a boy practices under the stern gaze of a metronome and a dark, outdoor balcony. In that work, music stands for discipline and modern anxiety. In “Woman at the Piano,” nearly a decade later, the mood is transformed. The metronome disappears, replaced by flowers and pattern; gray yields to coral red; severity becomes warmth. The comparison clarifies how the Nice years reoriented Matisse’s modernism from tension to consonance. The piano remains an instrument of order, but the order is now pleasurable, a voluntary immersion rather than a task.

The Figure’s Psychology and Modern Poise

The woman’s lowered eyes and quiet mouth convey concentration without strain. Her body leans into the keyboard with ease; her braid falls along the curve of her neck; her striped sleeve cups the wrist in a gesture both attentive and relaxed. She is not a virtuoso staging a public performance but a person absorbing herself in practice. This privacy is central to the painting’s tone. The viewer becomes a privileged witness to a small ritual of self-cultivation, a scene of modern domestic life in which art is woven into the day. The figure is neither fetishized nor anonymized; she is an axis around which the room’s rhythms cohere.

Ornament, Culture, and the Stage of the Room

Along the right edge a decorative band shows stylized instruments—violin, bow, and scrolling motifs—painted onto the wall. This self-quotation of musical imagery doubles the scene: instruments appear as both real and represented. The room is a stage designed for harmony, from the floral paper to the tiled floor to the vases echoing each other across the score. In this sense the painting is not simply a depiction of culture within the home; it is a proposal for a cultured environment, where objects are chosen for their ability to produce calm relationships. Decoration becomes a way of living with art rather than a separate category.

Feminine Agency and the Domestic Studio

Matisse’s interiors often feature women working, reading, or making music. In this painting the pianist is an active agent, literally producing the rhythms that the canvas translates into color. The domestic sphere, sometimes dismissed as passive, is here a space of creation. The piano is a tool; the room is a studio; the flowers are collaborators. This framing aligns with Matisse’s broader project to elevate everyday rituals to the level of art by attending to their form and harmony. The painting proposes a modern dignity rooted in attentive practice rather than in public display.

The Interplay of Vision and Touch

A distinctive pleasure of the canvas lies in how it balances seeing and feeling. You see the pattern, the notes, the keys; you also sense the texture of the paint, the grain of the piano’s surface, the soft nap of the blouse. Matisse never lets facture become fetish, but neither does he dissolve materiality into ideal form. The image remains sensuous in subtle ways: the way a brushstroke turns at a corner, the way yellow rolls over a fold of cloth, the way a petal is suggested by a single curved mark. These touches keep the painting close to the body, an apt complement to the tactile craft of playing.

Time, Repetition, and the Practice of Learning

The subject implies duration rather than a decisive moment. To practice is to repeat, to return to phrases with new attention. Matisse mirrors this temporality through repetition across the surface: arches follow arches, tiles follow tiles, stripes follow stripes, leaves echo leaves. Yet the repetitions are not mechanical. Small variations—a warmer red here, a cooler green there, a thicker line around the wrist—keep the pattern alive. The viewer reads the surface the way a musician reads a familiar score, alert to nuance within constancy. The painting thus honors the slow time of learning, the patient refinement that undergirds grace.

Modern Classicism and Lasting Resonance

Although the painting is rooted in domestic specificity and Nice-period taste, it also reaches toward a modern classicism: clear structure, balanced intervals, and an atmosphere of composed ease. That classicism is not retrograde; it is a contemporary answer to the early twentieth century’s appetite for rupture. In place of shock, Matisse offers coherence; in place of fragmentation, a field in which differences—red and green, pattern and plane, object and image—are reconciled without being erased. This is why the picture continues to feel fresh. It does not need to argue for modernity; it demonstrates it through the durable pleasures of relation.

Why the Painting Endures

“Woman at the Piano” endures because it condenses a philosophy of art into an unassuming scene. It affirms that harmony is not blandness but a demanding craft; that beauty can be rigorous; that color can think. The painting invites viewers to inhabit its tempo, to let the eye travel from stripe to key to blossom to arch, hearing in color what the figure hears in sound. Few pictures make domestic life feel so complete: a room transformed by attention, a person absorbed in practice, and a painter who knows how to make these elements sing in chorus on a single plane.