Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

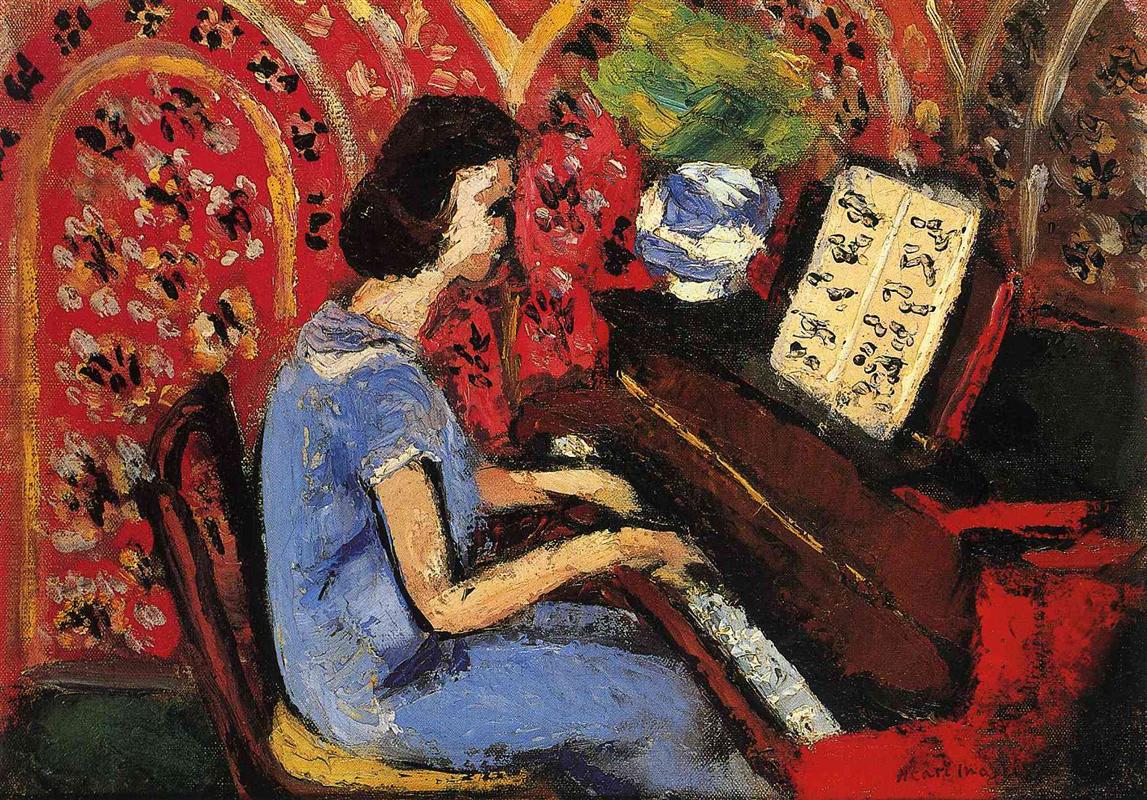

Henri Matisse’s “Woman at the Piano” (1924) compresses an entire world of rhythm, color, and attention into a compact interior. A young woman in a blue dress sits side-on at an upright piano, hands poised above a ribbon of white keys. An open score tilts toward the light. Behind her, a red wall patterned with pale arches and floral marks glows like a proscenium shell, and a small vase and greenery perch on the instrument’s ledge. The canvas is not a portrait of a particular pianist so much as a study of how looking and listening can occupy the same visual tempo. Matisse orchestrates ambient light, decorative pattern, and thick, decisive brushwork so that the room seems to hum with sound before a note is heard.

Historical Context and the Nice Period Ethos

Painted in Nice in 1924, the picture belongs to Matisse’s Mediterranean years, when he traded Fauvism’s explosive contrasts for a lucid modern classicism. In rented apartments turned studios he arranged screens, carpets, curtains, and furniture into experimental stages. He often chose subjects of cultivated leisure—reading, chess, and music—not as anecdotes but as opportunities to measure relations: warm against cool, curve against angle, near against far. Music occupied a special place in this program. Scores and instruments appear throughout the Nice pictures because they supply ready-made rhythms. An open page carries bars, rests, and notes; a keyboard divides light and dark into a steady meter. “Woman at the Piano” concentrates this vocabulary. It is a chamber piece in paint, played entirely in the key of red and blue.

Composition and the Architecture of Focus

Matisse builds the composition around two diagonals that intersect at the player’s hands. The first is the long, dark tilt of the piano from right to left; the second is the lighter counter-diagonal of the open score. At their crossing, the hands become the geometric and psychological center. Everything else supports that focus: the chair curves in parallel to the shoulder; the blue dress swells as a single volume; the patterned wall arcs like an acoustic shell behind the figure. The result is a sightline that feels inevitable: the eye enters at the blue dress, glides to the hands, then rises to the score and returns along the piano’s length to the red wall, looping back in a practiced phrase that echoes practice at the keyboard.

Pattern as Architecture

Instead of pushing deep perspective, Matisse turns pattern into architecture. The wall behind the player carries tall, arcade-like bands filled with pale blossoms and dark leaf prints. These repeating arches flatten the background into a decorative plane while also behaving like a soundboard that projects the figure forward. The pattern’s scale is carefully chosen. It is large enough to stabilize the wall but small enough not to compete with the figure’s silhouette or the black geometry of the instrument. The piano’s own lines—lid, keybed, and case—create a counter-pattern of strict horizontals and diagonals, a visual equivalent of musical staff lines. Pattern thus becomes the room’s scaffolding and its rhythm section.

Color Climate: A Red Ground and a Blue Solist

The palette is a saturated chord dominated by two primaries. The red field of the wall and scattered patches in the foreground establish a warm ground. Against this, the pianist’s dress gives a cool solo in cobalt and ultramarine tints. Where the two meet—at the neckline, cuffs, and edges of the chair—Matisse inserts olive and cream intermediaries so the colors converse rather than clash. The piano itself is rendered in kilned browns and chromatic blacks, never dead black, allowing the instrument to hold gravity without extinguishing the surrounding color. The open score is an island of paper white weathered with ochre, its notations simplified to looping signs that read both as music and as a pictorial scatter of small darks. The nearby vase introduces quick greens and a flash of blue-white porcelain, a high note that keeps the right side buoyant.

Light Without Theatrics

Nice-period light is ambient and benevolent. Here it arrives as a general wash from the right, gently illuminating the score and the player’s forearms. Because Matisse avoids sharp spotlights, shadows remain translucent and colored. Along the arm they turn olive; under the keys they read as a deep, warm brown; in the hair they carry plum and umber. This equalized illumination keeps the entire surface active. It lets color and pattern carry expression while ensuring that the hands—the site of action—have just enough lift to command attention.

Gesture, Touch, and the Physicality of Paint

The surface of “Woman at the Piano” holds its own music. Matisse lays the blue dress in with thick, buttered strokes that change direction as the body turns; scraping and reloading the brush leaves ridges that catch light like threads. The red wall is scumbled and dabbed, its motifs pressed into place with abbreviated moves that keep the pattern lively rather than literal. The piano’s dark planes are pulled in long, slightly elastic strokes; where the hand slows, the edges thicken, telling us precisely how much pressure the painter used. The white of the keys is not a flat strip but a sequence of short, varied touches that read as repeated notes. Everywhere the paint remembers the gesture that made it, so the viewer senses a performance parallel to the pianist’s.

Sound Made Visible

Matisse makes music visible through design. The keyboard’s alternating lights and darks translate into meter; the page of notation becomes a tight constellation of beats; the patterned wall pulses at a slower tempo, like sustained chords. The player’s blue volume is the melody line, moving over this accompaniment. Even the small vase behaves like a flourish at the end of a phrase. Nothing literal is depicted—no audience, no conductor, no identifiable piece—yet the canvas is saturated with the feeling of time kept and time released.

Space by Layers, Not Vanishing Points

The picture is shallow by design. Foreground and figure share the same plane as the piano; the wall is pressed forward into a patterned screen. Depth is declared by overlap and value rather than by linear recession. The result is intimacy. We stand close to the player’s shoulder, almost within the curve of the chair. This short interval suits the subject: music is heard at close range; practice happens at an arm’s length from the keys. The shallow space also protects the modern truth of the surface. Nothing dissolves into a tunnel; everything contributes to the immediate, breathable plane where painting happens.

The Hands as Centers of Meaning

At a literal level the hands play the piano; at a pictorial level they play the painting. Matisse gives them the most nuanced modeling on the canvas: a warm highlight along the knuckle, a cooler shadow at the wrist, a single quick notch for each finger joint. Their gestures are neither theatrical nor static. The left hand hovers in readiness, the right curves into a gentle action, suggesting a bar of music caught mid-phrase. Because the hands are two small, light forms nested in a sea of darks, they read instantly, making the viewer feel the moment of touch and the instant before sound.

Comparisons and Dialogues Within the Oeuvre

“Woman at the Piano” speaks to other Nice-period works where Matisse stages music against ornamental walls. The red shell behind the player recalls the acoustic screen in “Piano Player and Still Life” and the patterned settings in “Pianist and Checker Players,” but this canvas is tighter, almost pocket-sized, with brushwork thicker and more improvisational. It also echoes his still lifes from 1923–24, where open books and sheet music sit beside fruit and vases. Across these pictures Matisse pursues the same problem: how to translate the temporal art of music into the spatial art of painting without resorting to illustration. The answer, again and again, is rhythm in color and pattern.

Ornament Without Excess

Decoration can trivialize a subject if applied indiscriminately. Matisse avoids that trap by making ornament do structural work. The wall’s repeated arches stabilize the background and echo the piano’s curved case; the floral stamps distribute small darks that keep the red lively and link to the notes on the score; the table or stool beneath the figure is a single dark mass that grounds the blue. Because each decorative element also solves a compositional problem, nothing feels gratuitous. Beauty arises out of order, not out of embellishment.

Meaning Through Design

What does the painting propose? That focused attention—practicing music, painting a picture—has its own quiet grandeur. The player is not performing for a crowd; she is absorbed in the task. The room honors that absorption by removing distractions: pattern settles into architecture; color sustains mood; light is even. The scene becomes a model for concentration, Matisse’s favored form of leisure. In this sense the work is also a self-portrait of method. The pianist’s warm-cool exchanges, her measured rhythm, her equalized light mirror the painter’s decisions across the canvas.

How to Look, Slowly

Begin with the blue dress and let its broad, undulating planes carry you to the hands. Notice the quick shifts from warm to cool across the skin, the small knuckle accents, the thicker line where the thumb meets the palm. Step up to the score and count a few signs like beats in a bar. Slide back along the keyboard, feeling how the white keys’ broken strokes flicker like staccato. Drift into the red wall and trace one decorative arch from base to crest; watch how its rhythm is slower than the keys’ flicker. Return to the vase and the small sweep of green, then close the loop by settling again on the blue mass of the figure. Repeat the circuit. With each pass the relations clarify until the room’s visual music is unmistakable.

The Face and the Poise of Listening

The player’s face is built with remarkable economy. A slim, dark line secures the profile; a few accents locate brow, eyelid, and mouth; a compact shadow under the nose gives depth. The jaw softens into the neck with a warm, rosy transition. Nothing is individualized beyond what the pose requires, yet the head feels utterly present because it is placed with perfect weight between the red wall and the instrument’s dark. The player’s poise is that of someone who is listening as much as playing—another echo of Matisse’s ethic, in which looking is a kind of listening.

Material Presence and the Pleasure of Making

The work’s tactile energy—its ridges of paint, scraped edges, and consolidated masses—is not a side effect. Matisse allows the making to remain visible because it’s part of the meaning. Practice accumulates; so does paint. The viewer reads time in the way a blue stroke rides over a red one, in the way a thin dark line anchors a thick light patch, in the way the score’s off-white sits against a newly laid red. The painting is a trace of action, like fingerings in a well-used part.

Why the Painting Feels Contemporary

Although nearly a century old, the canvas reads as contemporary because it refuses narrative and virtuoso illusion in favor of clarity and tempo. Rooms today still run on patterns and screens; music remains a discipline of attention; the pleasure of thick paint has not diminished. Matisse’s choices—color as climate, pattern as structure, brushwork as record—are now part of the visual language of modernity. “Woman at the Piano” feels fresh because it embodies those choices without strain.

Conclusion

“Woman at the Piano” distills Matisse’s Nice-period ideals into a small, resonant stage. A blue figure plays within a red shell; pattern acts as architecture; color carries the mood; light remains kind; drawing is pared to what the form needs to stand. The music on the page becomes rhythm in paint; the keyboard’s alternations become a visual meter; the hands at the center conduct the whole. What might have been a sentimental interior becomes a lucid proposal about attention and harmony. Looking at the painting is an act of listening, and in that quiet cross-discipline lies its enduring charm.