Image source: wikiart.org

First Look: A Figure, A Pool, A Breath Of Color

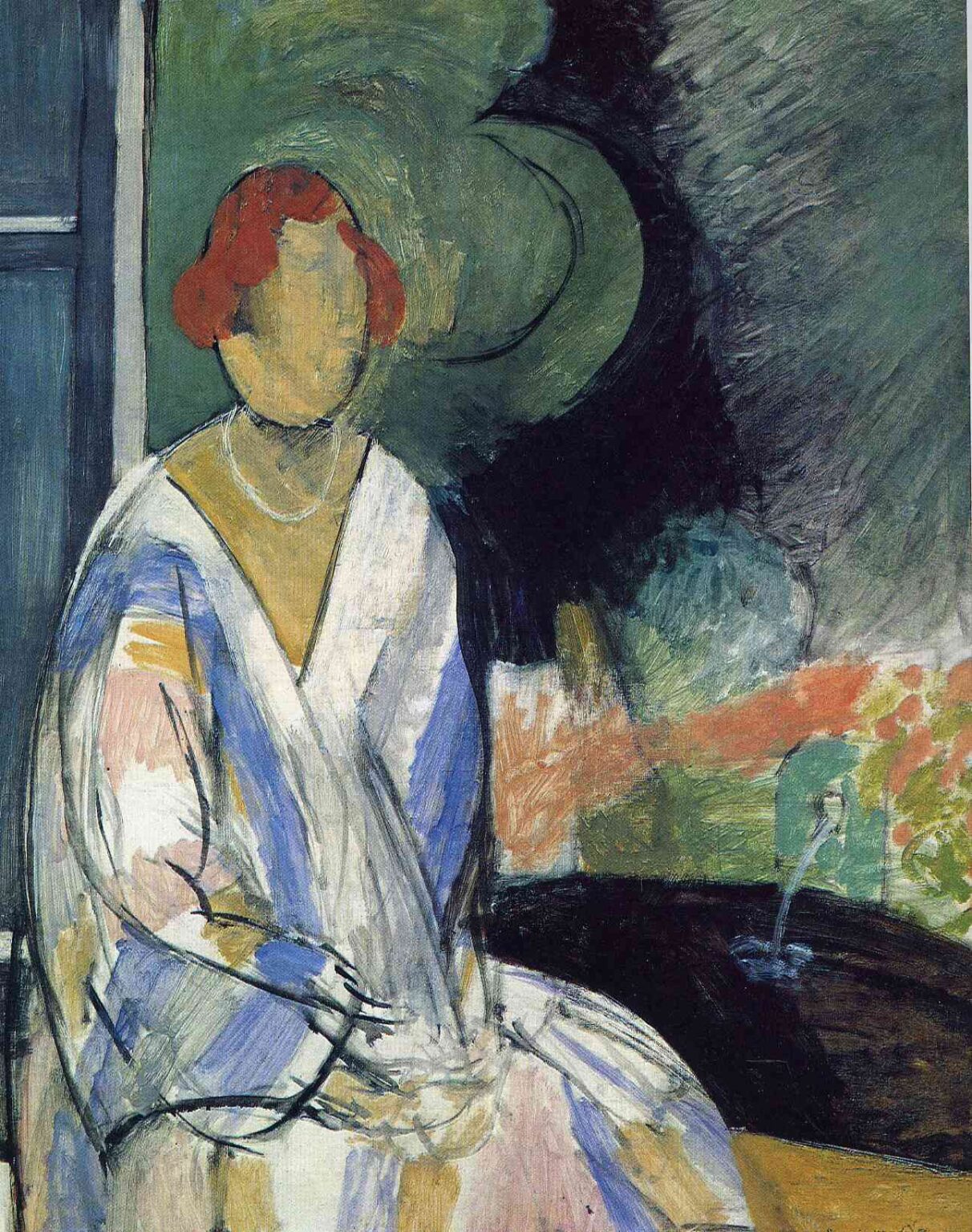

Henri Matisse’s “Woman at the Fountain” (1917) opens like a quiet exhale. A seated figure draped in a loose, banded robe occupies the left half of the canvas. Her copper-red hair forms a gentle cap against a swirling green ground. A dark basin occupies the lower right, and from it rises the thin, clear arc of a fountain jet, breaking the stillness with a single gesture. With black contour lines and swiftly laid color, Matisse compresses a scene into essentials: body, water, air.

1917 And The Turn Toward Clarity

The date is crucial. In 1917 Matisse moved toward a disciplined language that favored structure and restraint over his earlier Fauvist blaze. The war years narrowed travel and resources, but they sharpened the artist’s appetite for essentials. Interiors, still lifes, gardens, and the recurring model Lorette became laboratories for reduction. “Woman at the Fountain” belongs to this pivotal span, where black returned as a constructive color, planes were simplified, and the brushwork stayed frank. Instead of narrative detail, the painting offers a refined orchestration of line, hue, and rhythm.

Composition Built On Two Arcs

The picture is organized around two master gestures. The first is the arabesque of the woman’s robe, an envelope of white patterned with slanting strips of blue, ocher, lilac, and peach. The second is the sweeping semicircle behind her head that spins across the green wall like a breeze driven by the fountain’s mist. Together, those arcs counter the verticals of the window at far left and the downward drop of the robe’s lap, establishing a balanced choreography of curve and line. The black oval of the basin anchors the lower right, its flattened ellipse reinforcing the painting’s preference for surface over depth.

The Face That Isn’t There

Most striking is the nearly featureless face. Matisse leaves the oval open, with only a neck and a strand of pearls to assert presence. This is not an omission born of haste; it is a deliberate test of how little a portrait needs to feel animate. Hair, posture, and garment define character; the contour around the cheek and jaw line is so assured that eyes and mouth become optional. The anonymity turns the sitter into a type—modern womanhood as image—while protecting her privacy. Instead of reading psychology through features, we read it through gesture, color, and place.

Color Climate: Cool Whites, Damped Greens, And A Single Warm Flame

The palette is narrow and atmospheric. The robe’s white carries cool tints that drift between gray-blue and lilac; those tints echo the window’s blue frame. The ground is built from layered greens, some olive, some sea-glass, feathered into strokes that suggest breeze through foliage. A single concentrated warm note—the woman’s red hair—glows like an ember against that cool climate. The black pool and shadowy wall keep the composition grounded; a few terracotta strokes by the basin’s rim and at the robe’s hem add earth without stealing the scene. The water’s light blue spurt is a high note that keeps the painting breathing.

Black Contour As Structure And Music

Matisse’s black lines are not outlines in the academic sense; they are flexible chords that bind area to area. A continuous ribbon of black defines the robe’s sleeve, wrist, and cupped hand, crossing zones of white and pastel without losing energy. Another dark curve cinches the basin. Around the head, two incomplete rings in dark green and black hum like sound waves. The line is elastic, thickening and thinning with speed. Because it is musical rather than mechanical, it supplies structure while preserving the painting’s improvised feel.

Brushwork That Leaves The Making Visible

The paint handling is lucid, with visible decisions. In the robe, long, watery strokes run in the direction the fabric would fall, creating weight without modeling every fold. In the green wall, Matisse scrubs color in circular motions, leaving soft ridges that catch the light and evoke moving air. Where he needs density—around the basin, in the window mullion, along the robe’s sleeve edge—he loads the brush and draws once, letting the bristle’s path stand. That candor about process keeps illusion honest. We see a woman at a fountain and, simultaneously, the act of painting a woman at a fountain.

The Fountain As Motif And Metaphor

The thin stream rising from the basin is small in size but large in function. It articulates the painting’s sense of pause and refreshment, like a sustained consonant in a line of music. In Matisse’s world the fountain has symbolic weight: in Mediterranean gardens it is a promise of relief, a center of repose. Here it also becomes a painter’s device. Its arc echoes the larger green semicycles behind the figure, stitching background and foreground. Its blue hue brings the window’s color into the right half of the canvas, unifying the palette.

The Window: A Quiet Counterweight

At far left a vertical rectangle of blue injects architectural calm. It is barely described—two bars and a field—yet its geometry keeps the composition from drifting into pure arabesque. The window suggests interiority and exteriority at once. Is the woman near an open casement, the fountain in a courtyard beyond, or is the fountain an indoor basin? Matisse refuses literal answers. The geometry of the window simply offsets the organic forms elsewhere, a sober counterbalance to the painting’s swirls and curves.

Garment As Landscape

The robe behaves like a landscape of color planes. Broad stripes move like paths; the dark seam at the sleeve is a river; the sash compresses space as a horizon line does. This conversion of textile into terrain is a Matisse hallmark. It allows the viewer to read the body not as anatomy to be modeled but as a support on which color can be organized. The robe’s whites absorb neighboring hues and reflect them back, just as water does—a quiet visual metaphor tying garment to fountain.

Space Without Perspective

Depth in “Woman at the Fountain” is created by overlap, value contrast, and the logic of touch rather than by vanishing-point perspective. The basin overlaps the robe’s hem and immediately sits in front. The green wall recedes as its values lighten and its strokes feather out. The window’s verticals suggest a wall plane without defining an angle. The result is a space that can be entered by the eye, but that also reads as a designed surface. The viewer feels the room’s air more than its architecture.

The Eye’s Journey Through The Scene

The gaze typically begins at the warm red hair, the painting’s most saturated color, then floats clockwise along the haloing rings of dark green. It descends the V neckline to the pearl necklace, slips down the sleeve toward the cuff, and pauses at the lightly cupped hand. From there a dark arc leads across the black pool to the small blue jet of water, whose upward thrust sends the eye back toward the head. This circular motion echoes the compositional arcs and produces the painting’s meditative cadence.

The Poetics Of Reduction

Matisse argued that the essential is more expressive than the exhaustive. This canvas enacts that belief. The sitter’s face is a luminous blank; the fountain is a single stroke; the window is two bars. Yet the scene is convincing because relations are precise: warm against cool, curve against straight, dense against thin. Reduction is not emptiness; it is concentration. The more the painter removes, the more the remaining elements must carry meaning, and here they do so with ease.

Between Portrait And Allegory

Because the face is generalized, the figure floats between portrait and allegory. She could be Lorette, Laurette, or another model from the Issy and Paris studios. But she is also an emblem: modern woman seated at a source of refreshment, poised between interior and exterior, clothed in a robe that behaves like a painted page. The fountain links her to a long lineage of bathers and courtyard figures in Mediterranean art, yet the black contours and abbreviated features declare a modern temperament. The painting belongs to both traditions at once.

Kinship With Nearby Works

“Woman at the Fountain” converses with Matisse’s interiors from 1916–1918: “The Rose Marble Table,” “The Painter and His Model,” and the sequences devoted to Lorette in turbans, jackets, and robes. All share the use of black as a color, the limited palette, the willingness to leave information out, and the delight in balancing pattern with large, quiet fields. This canvas is perhaps more experimental in its abandonment of facial detail and in the emphasis on atmospheric ground swirling like a weather map around the sitter’s head.

Gesture, Stillness, And The Sound Of Water

One of the picture’s subtle pleasures is its sense of sound. The airborne green strokes read like a soft rotary breeze; the falling arc of water suggests a hush at impact; the robe’s long strokes hum quietly down the picture’s left. Nothing is loud. The whole becomes what Matisse famously sought: a visual arrangement that offers calm. Even the black pool, which might threaten heaviness, feels like velvet rather than tar, a restful depth rather than a void.

The Ethical Distance Of The Viewer

By refusing to map a face, Matisse sets a respectful distance. The viewer is admitted to the room but kept from trespassing on personal identity. Attention is shifted from who the sitter is to what the painting does. We contemplate the act of seeing rather than the act of judging. That ethical distance feels especially modern. It converts the encounter from curiosity about a person into a study of sensation, relation, and presence.

Lessons For Painters And Viewers

This work offers durable lessons. A small, carefully placed warm accent can govern a cool composition. Black can function as architecture for color rather than as mere shadow. Edges that alternate between sealed and open let a surface breathe. A motif—here, the fountain—can be both pictorial glue and metaphoric pulse. Above all, a figure can be powerfully present without descriptive excess; suggestion, if tuned precisely, can feel more real than transcription.

Why “Woman at the Fountain” Endures

The painting endures because it is generous and exact. Generous, because it leaves room for the viewer’s imagination to complete what is implied. Exact, because every stroke is purposeful and every relation is tuned. It embodies Matisse’s mature conviction that clarity is not coldness and that calm can be the most radical modern sensation. The woman sits, the fountain arcs, the air turns, and the room holds its breath. Nothing more is needed.