Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

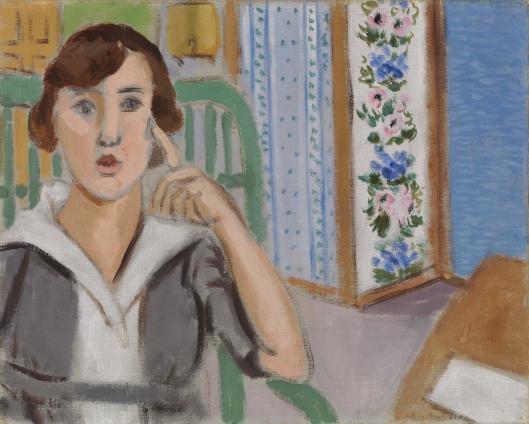

Henri Matisse’s “Woman and Screen” (1919) captures a poised interval inside a light-filled room. A woman sits in a green chair, finger raised to her temple as if catching a thought mid-flight. Behind and to the right, a folding screen blooms with vertical bands of pattern—one strewn with blue dots, the other with rose-and-blue garlands—while a small table in the foreground holds a sheet of paper like a pause mark. The image is modest in scale and subject, yet it radiates the clear, chamber-music harmony that defines Matisse’s early Nice period. With a handful of planes and a few carefully tuned colors, he turns a quiet domestic scene into a study of attention, pattern, and modern pictorial space.

Historical Context

Painted in the first year after the Armistice, the work belongs to a moment when Matisse shifted decisively toward interiors, screens, and seaside light. After a decade marked by the shock of Fauvism and the catastrophe of war, his art sought steadiness in habitable rooms. These Nice pictures temper the blazing color of 1905–06 without surrendering its conviction that color is structure. “Woman and Screen” embodies that recalibration. It is neither a virtuoso display of brush fireworks nor an academic portrait; it is a modern interior in which decoration is not accessory but subject, and in which a person’s thoughtfulness becomes the painting’s emotional center.

The Motif and Immediate Impression

At a glance, the painting reads as a conversation between a figure and a vertical ornament. The sitter’s gray dress and crisp white collar set a cool, lucid tone; the green slats of her chair echo the alertness of her pose; the screen’s florid panels introduce bloom and rhythm. The composition feels airy, the paint thin enough in places to let the weave of the canvas breathe. Nothing is over-explained. Matisse offers just enough specificity—an eyebrow’s arc, a knuckle, a petal cluster—to make presence felt, then lets color fields and linear accents carry the rest.

Composition and Framing

Matisse builds the image from a few large rectangles and bands. The figure and chair occupy the left half, cropped so the sitter’s arm and shoulder press against the picture edge. The right half opens to the hinged screen and a wedge of blue wall beyond. The tabletop intrudes from the lower right corner as a warm, angled plane, its diagonal countering the screen’s verticality. This asymmetrical split is crucial: it makes the screen a co-protagonist without displacing the sitter, and it gives the eye a path from human presence to decorative field and back again.

The Role of the Screen

The screen is both architecture and ornament. Its two decorated leaves do not merely decorate the background; they create a second kind of space—flat, patterned, theatrical—against which the figure’s modeled head and hands read with greater clarity. The floral panel, with its vine-bound pink and blue blossoms, suggests textiles Matisse loved to collect, while the neighboring band of blue dots acts like a visual metronome. The screen’s hinge and slight corner recession announce that this is a movable object, a device for structuring space within a room. Matisse uses it to declare the painting’s modern premise: flat patterns can make space as surely as perspective lines.

Color Architecture

The palette is restrained and coherent. The figure is keyed to cool grays and whites, lifted by flashes of warm skin. The chair is a leafy, medium green—a spring note that ties figure to room. The screen’s floral pinks and blues provide chromatic melody without overpowering the whole; their saturation is moderated so they harmonize with the calm gray floor and the lilac-tinged wall. The small tabletop triangle warms the lower right like a muted ochre chord, and the blue panel at far right supplies a cool horizon. The result is a climate rather than a spectacle: a soft, coastal light in which colors converse rather than compete.

Line, Contour, and Simplification

Matisse’s contour does the quiet work of structure. It tightens at the chin and nostril, relaxes along the collar, and flickers around the fingers poised at the temple. These lines are not hard borders but living edges that swell and thin, letting planes meet with breath. The chair’s slats are drawn in economical strokes that suggest wood without fuss; the screen’s vines are written with looping, calligraphic ease. Simplification is principled, not lazy. The figure’s face, for example, is built from a few planar turns—the bridge of the nose, the cheek, the upper lip—yet it carries alertness and a hint of speech.

Light and Atmosphere

Light is even and benevolent, the kind that arrives through a high window on a hazy day. It makes little drama of cast shadow; instead it clarifies colors and keeps edges soft. The white of the collar is not icy but milk-warm; the gray dress lifts where light touches the shoulders; the green chair holds a matte brilliance; the floral screen glows without glare. This tempered light is a hallmark of the Nice interiors. It lets pattern and contour do the expressive work while preserving a sense of real air in the room.

Space and the Modern Picture Plane

The painting acknowledges depth without courting illusion. Overlap—chair before torso, figure before screen, screen before wall—cues recession; the angled tabletop adds a second diagonal that opens the corner slightly. But the patterned screen and the uniform handling keep space shallow, closer to a theater set than to a deep chamber. This is not a defect; it is the chosen modern arena in which flat color and drawn line can maintain their integrity while still hosting a believable room.

Gesture, Expression, and Psychology

The sitter’s raised finger is the picture’s most articulate gesture. It registers as concentration or the beginning of speech—a thought touching down at the temple. The mouth, softly open, reinforces that sense of near-speech, as though the figure were about to share what she has been turning over in her mind. Nothing about the body is slack: the shoulders tilt, the neck lengthens slightly, the eyes focus outward but not confrontationally. Matisse refuses melodrama and arrives at a subtler truth: attention has a posture.

Furniture, Paper, and the Signs of Work

The warm tabletop and the small sheet of white paper suggest note-taking, letter-writing, or a drawing just set aside. These modest objects keep the painting from drifting into abstraction by tying it to a lived moment. They also echo the painting’s own activity: looking, thinking, and marking. The green chair’s back slats repeat behind the head like a gentle stave of music, implying that the furniture is not inert but participates in the room’s rhythm.

Pattern and Plainness

Matisse balances patterned and unpatterned fields with care. The floral screen and dotted band supply ornament; the dress and collar offer large plain shapes that absorb that energy and keep the room from becoming decorative noise. This balance is structural, not merely tasteful. Pattern acts like a moving voice in a composition, while plain fields carry the harmony. The figure is placed where the two meet, a living mediator between decoration and clarity.

Material Presence and Brushwork

The paint is handled with openness. Thin scumbles let the canvas weave show through in the wall and floor; more loaded strokes build the floral knots and the green chair. The face and hands are painted with light, elastic touches, preserving the freshness of first decisions. The painting feels made in one sustained sitting or in a few quick passes, not labored over weeks. That sense of immediacy suits the subject: a thought caught rather than posed.

Dialogue with Tradition

Screens have long served painters as tools for building space and as carriers of ornament—from Japanese byōbu to eighteenth-century French interiors. Matisse borrows the device and modernizes it. He does not paint a meticulously described chinoiserie; he paints a screen as a flat, patterned partner to the figure. The update keeps the decorative alive while placing it under the governance of the painting’s overall design. The result honors tradition without reenactment.

Relations to the Nice Period

“Woman and Screen” converses with other 1919 works—balcony scenes, reading figures, and studio nudes—through shared commitments: shallow staged space, living contour, and color as architecture. Where the odalisques revel in textiles, this painting trims back to one flamboyant object, the screen, letting the figure’s thinking gesture lead. It shows how supple Matisse’s Nice vocabulary was: the same elements could produce languor, reverie, or, as here, alertness.

Anticipations of Later Work

The floral silhouettes, scalloped edges, and clear figure-ground rhythms anticipate the cut-outs of the 1940s, where leaves and petals become pure shapes pinned against color. Even the way the screen shares the stage with the sitter foreshadows later pictures in which pattern and figure merge into one decorative logic. The seeds of that future lie in the economy and boldness of this 1919 canvas.

How to Look

A rewarding path begins at the sitter’s hand and temple, drops to the white collar’s V, moves outward along the green chair slats, and slides to the patterned screen. From there, step to the blue wall and down to the warm tabletop triangle and sheet of paper; then return along the arm to the face. This loop mirrors the painting’s structure: thought, environment, trace of work, thought again. Each circuit slows the eye until the room’s quiet rhythm becomes palpable.

Meaning Today

For contemporary viewers, the image reads as a portrait of attentiveness in an over-noisy world. The screen does what screens once did in rooms: it organizes space, grants privacy, filters light. The painting enacts the same service for the gaze, screening out distraction so a single person and a few patterns can be seen with care. Its modernity lies in that discipline. It proposes that a pared-down interior, tuned by color and line, is enough to host a full experience of looking and thinking.

Conclusion

“Woman and Screen” distills Matisse’s early Nice period into a lucid conversation between presence and pattern. A seated woman, alert and almost speaking, shares the stage with a floral screen that turns decoration into structure. Cool grays, greens, and blues establish climate; a warm tabletop and skin tones add human temperature. Space is shallow, brushwork frank, contour alive. Nothing is flamboyant, everything participates. The painting invites the viewer into a room designed for attention and shows how, in Matisse’s hands, even the simplest elements—chair, screen, paper, gesture—can combine into a durable harmony.