Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

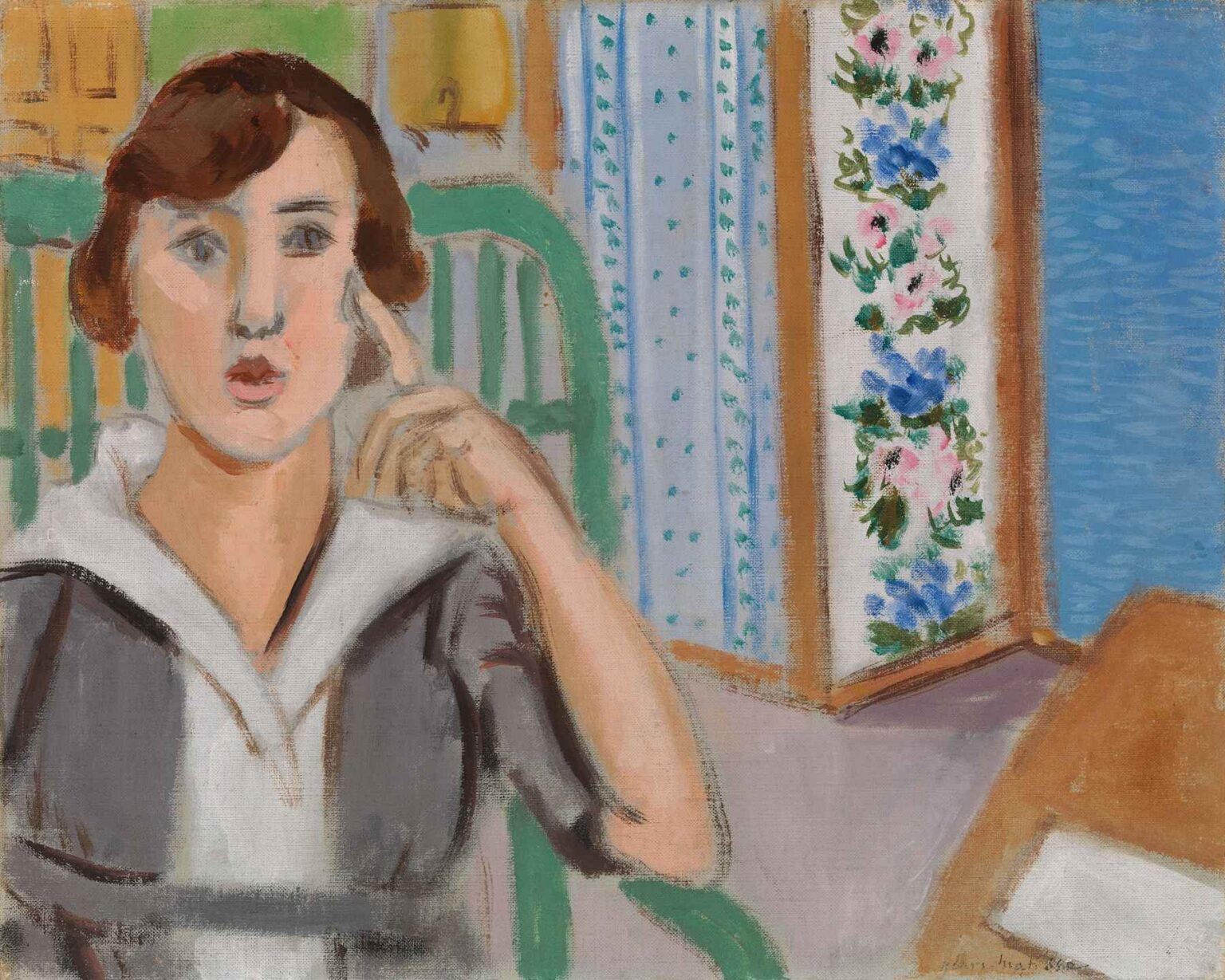

Henri Matisse’s Woman and Screen (1919) captures a moment of contemplative stillness within an interior space defined by pattern, color, and formal elegance. Painted in the aftermath of World War I, this work reflects Matisse’s ongoing exploration of decorative harmony and psychological nuance. Rather than presenting a grand narrative, Woman and Screen focuses on the interior life of its subject—a seated woman gazing outward, her posture and expression inviting viewers to share in her quiet introspection. The juxtaposition of figure and screen allows Matisse to investigate the dialogue between animate presence and ornamental backdrop, between intimate solitude and the broader world implied beyond the frame. Over the course of this analysis, we will examine the historical circumstances surrounding the painting, dissect its compositional structure, delve into its chromatic strategies, and explore its thematic resonances within Matisse’s mature oeuvre.

Historical Context

The year 1919 marked a pivotal moment for Europe and for Matisse himself. The armistice of November 1918 had ended the bloodiest conflict in human history to that point, leaving societies traumatized and artists searching for new paths forward. Matisse, having served briefly as a medical orderly, returned to Paris determined to reaffirm art’s capacity for solace and renewal. His wartime experiences deepened his conviction that beauty could heal the psyche and restore a sense of order. During the mid-to-late 1910s, Matisse’s palette evolved from the explosive chromatic contrasts of Fauvism toward more harmonious, measured combinations of hue. At the same time, the flattened surfaces championed by Cubism influenced his spatial treatment, encouraging him to compress perspective and foreground pattern as an organizing device. Woman and Screen emerges from this crucible of reflection and experimentation—a painting that balances the decorative and the introspective, the formal and the emotive.

Subject and Narrative

At the center of Woman and Screen sits a young woman, her body positioned slightly at an angle to the picture plane. Dressed in a simple gray and white blouse, she rests her right elbow on the armrest of a green-painted chair while her index finger touches her temple, a classic gesture of thoughtfulness. Her gaze is directed toward the viewer—or perhaps beyond, as though lost in private reverie. Behind her, a folding screen unfolds into the room, each panel adorned with distinct motifs: delicate floral sprays, vertical stripes of tiny blossoms, and a flat field of blue suggesting water or sky. To the right, a small table bears the corner of a book or writing pad, hinting at intellectual pursuits, correspondence, or creative labor. The painting offers no explicit storyline; instead, it invites viewers to inhabit the subject’s mental space, to ask what thoughts occupy her mind and what worlds lie beyond the screen.

Compositional Structure

Matisse’s compositional genius in Woman and Screen lies in his ability to orchestrate multiple pattern fields and architectural elements without sacrificing focus on the figure. The painting can be understood through three interlocking compositional zones:

Foreground Zone: The seated woman and her green chair form the visual anchor. The chair’s vertical slats echo the vertical lines of the screen behind, creating a sense of formal continuity. The angle of her arm and the curve of her shoulder introduce diagonal counterpoints, preventing the composition from becoming overly static.

Middle Zone: The folding screen dominates the central area. Its panels are delineated by thin, warm-toned borders that both segment and unify the decorative motifs. Matisse balances three distinct patterns—floral sprays, dotted vines, and a solid blue field—ensuring that no single panel overwhelms the others. The screen functions as both setting and secondary subject, its rhythms dialoguing with the figure’s posture.

Secondary Elements: The table in the lower right corner, occupied by the edge of an open book or pad, and the suggestion of a curtained window at left introduce ancillary narrative cues. These elements, though rendered with economy, contribute subtle diagonal axes that lead the eye back to the seated woman, reinforcing her primacy.

By integrating these zones with overlapping arcs and intersecting lines, Matisse creates a cohesive pictorial structure in which figure and decoration coexist in harmonious tension.

Use of Color and Pattern

Color serves as the primary vehicle for emotional tone and spatial definition in Woman and Screen. Matisse’s palette here is both restrained and resonant:

Figure Palette: The woman’s skin is painted in warm, flesh-toned pinks and creams, offset by the cool gray of her blouse and the stark white collar. Subtle modulations in tone—rosy highlights on cheeks, pale lavender shadows under her chin—lend her presence a quiet warmth without resorting to heavy modeling.

Chair and Table: The green of the chair, a muted spring hue, contrasts gently with the warm terra-cotta floor beneath, which is barely visible but suggested through thin strokes of ochre. The table corner and the book’s pale tan cover provide small accents of golden warmth.

Screen Motifs: Each panel of the screen features a distinct chromatic scheme: lavender and green florals against white; pale blue vines on a neutral ground; and a deep, almost cobalt blue panel that anchors the composition’s right side. Matisse juxtaposes these areas with skillful attention to color relationships, allowing cools and warms to play off one another. The lavender blossoms echo the slight purple underpainting glimpsed beneath the woman’s garment, forging chromatic links across the canvas.

Pattern in Woman and Screen is less about surface ornament than about spatial rhythm. The floral sprays are painted with loose, gestural strokes, their organic irregularity contrasting with the precise vertical alignment of the chair and screen frame. The dotted vines introduce a rhythmic punctuation that guides the viewer’s eye upward, while the solid blue panel offers a moment of pictorial respite—a visual “breath” amid the ornament. Through these orchestrations of hue and motif, Matisse creates a decorative environment that both frames and enlivens the solitary figure.

Spatial Construction

Although Woman and Screen portrays an interior setting, Matisse deliberately eschews the strict application of linear perspective. Instead, he flattens space through overlapping planes and pattern fields. The chair, figure, screen, and table exist on slightly offset levels, their edges meeting in shallow relief rather than receding dramatically into depth. Overlap—such as the screen’s panels partially obscuring the chair’s back slats, or the woman’s arm in front of the screen frame—signals relative position without constructing a full volumetric interior.

This compression serves multiple purposes. First, it highlights the painting’s decorative aspects, inviting viewers to appreciate the surface as a tapestry of color and pattern. Second, it underscores the subject’s psychological isolation: she occupies a discreet pictorial niche, encircled by ornamental motifs that both protect and contain her. Finally, the flattened treatment anticipates Matisse’s later experiments with cut paper, where space collapses entirely into color-form relations. In Woman and Screen, the balance between spatial suggestion and surface unity achieves a tension that is central to the painting’s emotional impact.

Brushwork and Technique

Matisse’s brushwork in Woman and Screen combines broad, assured strokes with finer, calligraphic lines. Large areas—the chair’s back, the solid blue panel—are blocked in swiftly, their pigment applied with minimal layering. In contrast, the floral sprays and dotted vines on the screen receive more delicate treatment, the blossoms built up through small, dappled touches. The woman’s face and hands are modeled through thin glazes and subtle color shifts, preserving the luminosity of the underlying canvas.

Impasto is sparingly used; where present, it accentuates highlights on the chair’s arm or the book’s cover. Matisse’s technique stresses economy: every stroke serves either to define form, to articulate pattern, or to balance chromatic relationships. The visible directionality of his brushstrokes—the sweeping arcs on the blouse, the stippled petals on the screen—remains palpable, reminding viewers of the painting’s materiality even as they admire its decorative harmony.

Emotional and Psychological Atmosphere

Despite its decorative surface, Woman and Screen conveys a palpable emotional resonance. The subject’s head-tilt and finger-to-temple gesture suggest thoughtful engagement—perhaps pondering a letter on the table, recalling a distant memory, or simply resting in quiet contemplation. Her wide eyes and slightly parted lips hint at curiosity or mild surprise, drawing viewers into her mental world.

The surrounding patterns and colors contribute to this atmosphere. The lavender florals evoke a sense of gentle tranquility, while the dotted vines suggest growth and the passage of time. The solid blue panel—cool, deep, and unpatterned—introduces a note of introspection, as though the woman’s inner thoughts mirror that expanse of serene color. In this way, Matisse transforms a mundane moment of repose into a subtle psychological portrait, capturing the interplay between external décor and inner life.

Symbolism and Thematic Resonance

While Matisse did not typically embed heavy symbolic codes in his work, Woman and Screen invites thematic readings through its use of gesture, setting, and motif:

Gesture of Thought: The finger-to-temple pose has long signified intellectual engagement or introspection in Western art. Here, it may reference the act of reading, writing, or creative reflection suggested by the book on the table.

Folding Screen: Traditionally used to divide space, screens also carried connotations of privacy and revelation. In this painting, the screen both frames the subject and hints at unseen realms beyond—emotional, intellectual, or physical.

Floral Motifs: Flowers have historically symbolized transience and renewal. The blossoming sprays on the screen may allude to cycles of thought and feeling—moments of inspiration budding amid daily routine.

Color Fields: The contrast between patterned panels and the solid blue section can be read as a dialogue between complexity and simplicity, between the ornamental aspects of life and the moments of unpatterned stillness that allow introspection to flourish.

Placement in Matisse’s Oeuvre

Woman and Screen occupies a significant position in Matisse’s evolution from Fauvism toward his later mature style. While early Fauvist works emphasized exaggerated color and wild brushwork, this 1919 painting reveals a more disciplined approach to hue, pattern, and compositional harmony. It builds upon his earlier interior scenes—balconies, lounge chairs, and odalisques—by integrating the decorative screen as a principal element, presaging the heightened flattening and pattern integration of his 1920s work.

Moreover, Woman and Screen foreshadows Matisse’s cut-paper “gouaches découpées” of the 1940s and 1950s. The painting’s embrace of surface pattern, bold color areas, and simplified forms would find new expression in the paper cutouts, where he further compressed space and distilled motifs. In the arc of his career, Woman and Screen represents a bridge between the painterly exuberance of his youth and the graphic purity of his late abstractions.

Influence and Legacy

The flattened space, decorative patterning, and intimate subject of Woman and Screen influenced both contemporaries and later generations. Cubist artists, already challenging traditional perspective, found in Matisse’s approach a complementary model for integrating pattern and form. Mid-century Abstract Expressionists and Color Field painters drew inspiration from his use of broad color zones and the visible gesture of paint application.

In interior design and textile circles, Woman and Screen and similar Matisse works sparked interest in bold, art-inspired patterns. The painting’s combination of figurative content and ornamental motifs anticipated the Pattern and Decoration movement of the 1970s, which reclaimed decorative arts as a legitimate arena for contemporary practice. Even today, designers and artists reference Matisse’s interiors for their harmonious balance of color, form, and psychological nuance.

Conclusion

In Woman and Screen, Henri Matisse orchestrates a subtle symphony of figure, pattern, and color to capture a moment of introspection within an ornamental interior. Through his masterful compositional structure, harmonious chromatic interplay, and sensitive brushwork, he transforms a simple scene of repose into a rich exploration of the dialogue between outer environment and inner life. The painting stands at the crossroads of Matisse’s Fauvist past and his graphic abstractions to come, embodying his belief in art’s capacity to reveal beauty and depth in everyday moments. Over a century after its creation, Woman and Screen continues to resonate—inviting viewers to linger in its decorative splendor and to contemplate the timeless act of quiet reflection.