Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

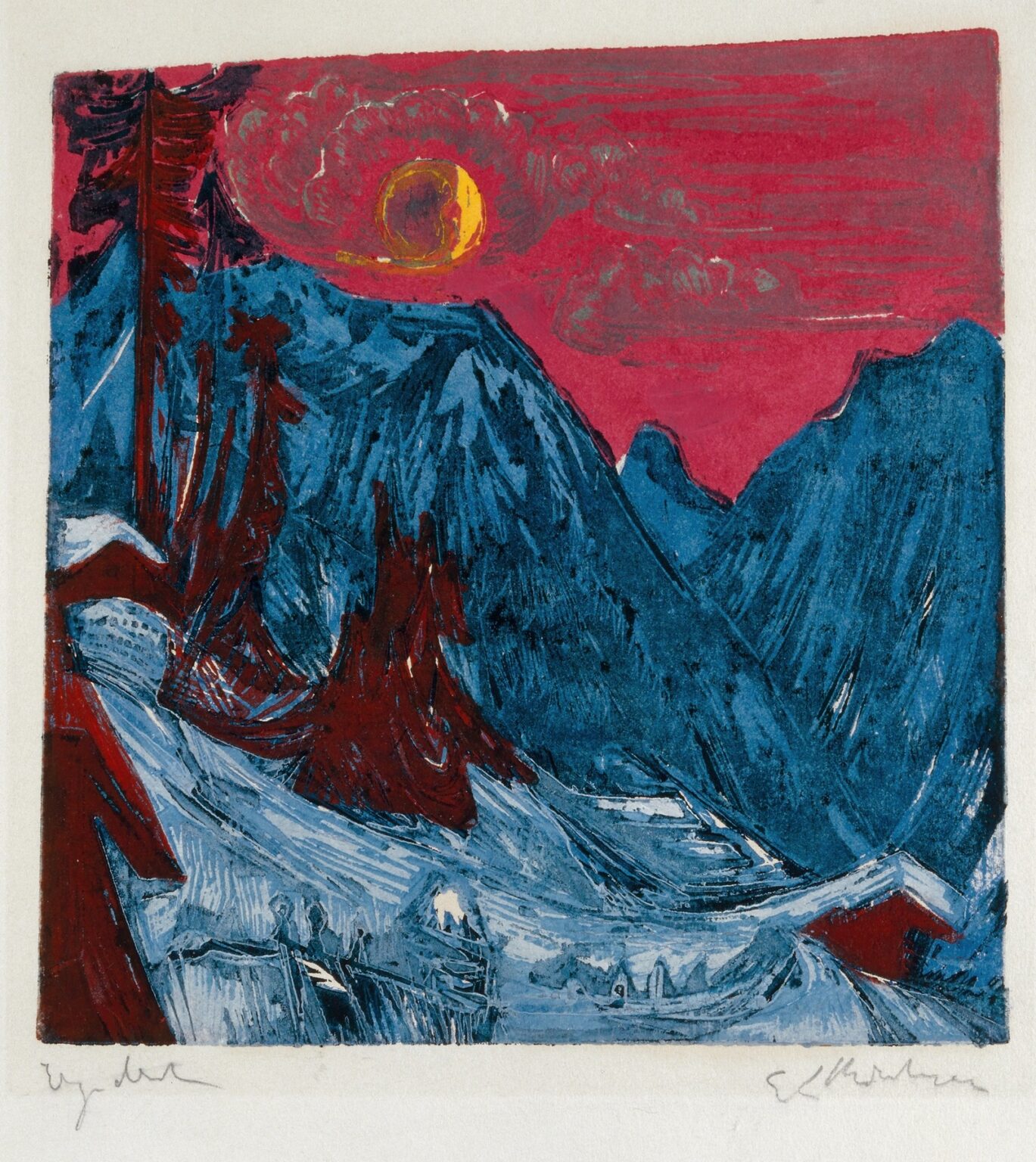

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Winter Landscape in Moonlight (1919) emerges as a haunting testament to the artist’s postwar sensibility and his mastery of the woodcut medium. Executed shortly after the cataclysm of World War I, this work captures both the austere grandeur of the Alpine environment and the deep emotional resonance of nocturnal solitude. The scene unfolds beneath a crimson sky pierced by a luminous crescent moon, while jagged mountain silhouettes and snow-laden slopes evoke a landscape at once familiar and otherworldly. In this analysis, we will explore the painting’s historical context, technical innovations, compositional strategies, color dynamics, thematic depth, and enduring influence, demonstrating how Kirchner fused Expressionist fervor with a poetic engagement with nature to create a work of compelling psychological intensity.

Historical Context and the Post-War Climate

By 1919, Europe was grappling with the aftermath of unprecedented destruction. Kirchner himself had served briefly in the German army before being discharged for health reasons, and he spent the war years in Switzerland—first at Lake Zurich, then in Davos, where he sought solace and recuperation. The alpine surroundings became both a refuge and a crucible, reflecting his inner turmoil and physical frailty. Like many Expressionists, Kirchner turned to the natural world as a source of renewal, yet his postwar landscapes also convey a sense of displacement and mourning. Winter Landscape in Moonlight embodies this duality: the pristine snow and silent pines suggest healing isolation, while the blood-red sky and stark forms hint at trauma’s lingering shadows. In this context, the work transcends mere topographical depiction, serving as a visual poem that channels collective grief and personal resilience.

Medium and Technical Innovation

Although Kirchner originally made his name as a painter, he embraced woodcut printing with fervent enthusiasm during and after the war. Woodcuts allowed him to carve directly into wood blocks, removing material to create bold contrasts and raw textures. For Winter Landscape in Moonlight, he employed a multi-block technique: each color field—crimson sky, deep blue mountains, and pale snow—required a separate carved block and careful registration. This labor-intensive process demanded precision and spontaneity: once ink met the block, possibilities for revision vanished. Kirchner exploited these constraints to his advantage, allowing the wood grain to show through and embracing slight misalignments as traces of human touch. The result is a dynamic synergy between precision and accident, where chiseled contours and luminous overlays generate a pulsating surface that captures the unpredictable rhythms of nature and emotion alike.

Composition and Spatial Structure

At the heart of Winter Landscape in Moonlight lies a daring compositional scheme that balances monumentality with intimacy. A tall fir tree on the left margin anchors the scene, its dark silhouette contrasting sharply with the angular slopes of the mountains behind it. These peaks ascend in stepped silhouettes, guiding the eye upward toward the blood-red sky and its glowing moon. In the lower right, a small chalet—rendered in simplified form—provides a human scale, suggesting habitation yet emphasizing the vastness beyond. Kirchner eschews traditional linear perspective: foreground and background interlock through overlapping color planes rather than receding lines. This flattening effect compresses spatial depth, drawing the viewer into a cohesive pictorial arena where sky, mountain, and snow merge into a unified field of emotional resonance. The interplay of vertical, diagonal, and horizontal elements generates visual tension, mirroring the collision of tranquility and unease that defines the work’s atmosphere.

Color Palette and the Drama of Light

Color in Winter Landscape in Moonlight functions as narrative and mood itself. Kirchner abandons naturalistic snow whites and sky blues in favor of a restricted yet dramatic triad: scarlet sky, cobalt mountain, and bone-white snow. The crimson horizon infuses the night with an almost apocalyptic glow, while the moon’s halo—ringed in orange and yellow—casts an eerie luminosity across the peaks. Cobalt and ultramarine tones of the mountains stand in stark counterpoint, their textures carved to suggest both solidity and mystery. The snowfields take on a spectrum of whites, from ivory to pale cerulean, capturing the moonlight’s subtle modulations. By leveraging such heightened contrasts, Kirchner transforms a simple nocturnal scene into a stage for conflicting forces: warmth and chill, rest and unrest, beauty and disquiet. This chromatic boldness exemplifies Expressionism’s faith in color as raw emotional substance rather than optical fact.

Mood, Atmosphere, and Psychological Resonance

While the work depicts no human figures, its emotional charge is unmistakably human. The solitary chalet, dwarfed by its surroundings, becomes a locus of human yearning—shelter against an imposing wilderness. The jagged trees and craggy peaks seem to whisper secrets of isolation and endurance. In Kirchner’s vision, the moonlight does not soothe; it illuminates with uncanny clarity, revealing both the grandeur and the alienation of the natural world. Viewers may feel the hush of snow underfoot, yet also sense a latent tremor—as if the terrain itself pulses with hidden life. This oscillation between calm and anxiety encapsulates postwar psychological states: desire for peace tempered by memories of violence. The painting’s silence speaks volumes, inviting each observer to project personal fears and hopes onto its elemental forms.

Symbolism and Thematic Depth

Beneath its immediate appeal, Winter Landscape in Moonlight brims with symbolic undertones. Winter, long a metaphor for dormancy, death, and purification, here suggests a season of introspection—a necessary stillness after the tumult of war. The moon, crescent yet full of potential, becomes a symbol of renewal as well as melancholy. Its shifting phases echo the cycles of human psyche—illumination interspersed with darkness. The chalet’s faint glow in the nightpoints to resilience: even in the coldest expanse, life persists. Trees—ancient witnesses to history—stand like silent sentinels, reminding viewers of continuity amid chaos. Kirchner weaves these motifs without explicit narrative, allowing symbolic meanings to emerge organically through the synergy of color, form, and spatial arrangement.

Technique as Expression: Carving, Registration, and Texture

A close examination of the print reveals Kirchner’s nuanced handling of technique as expressive content. The carved lines vary in depth and width: some are bold grooves that define mountain ridges; others are fine scratches that evoke frost or bark. Slight misregistrations—where the blue block overlaps the red sky—are not flaws but living evidence of the hand at work. Kirchner deliberately left wood grain visible in areas of snow and sky, lending the surface an organic texture that resonates with the unevenness of natural terrain. Ink density fluctuates, creating areas of pure color and others where paper shows through. These variations generate a tactile momentum, encouraging viewers to trace the carved rhythms with their eyes. By foregrounding process alongside image, Kirchner propels the woodcut beyond illustration, transforming it into a visceral encounter with materiality itself.

Place in Kirchner’s Oeuvre and the Alpine Series

Winter Landscape in Moonlight belongs to a significant series of Alpine prints and paintings Kirchner produced during his Swiss exile. Unlike his earlier Moritzburg landscapes, these Davos works bear the imprint of physical hardship—snow blindness, tuberculosis, and psychological exhaustion shaped his vision. He often returned to winter scenes, exploring themes of isolation and elemental struggle. This particular print stands out for its radical color inversions and its synthesis of Expressionist intensity with a deeply felt sense of place. Within Kirchner’s broader oeuvre, it signals his successful translation of personal adversity into artistic renewal, and it anticipates later developments in modern printmaking where color woodcut would gain prominence as a medium for expressive abstraction.

Influence on Modern Printmaking and Legacy

Kirchner’s postwar woodcuts exerted substantial influence on both contemporaries and subsequent generations. His willingness to embrace misregistration and visible wood grain challenged prevailing standards of technical perfection. Artists such as Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Emil Nolde, and Asia-Pacific printmakers drew inspiration from his multi-block color experiments, seeing woodcut as a medium capable of emotional immediacy on par with painting. In the decades following Kirchner’s death, the Expressionist woodcut tradition revitalized print art, paving the way for Abstract Expressionists and later modernists who viewed printmaking as a laboratory for spontaneous mark-making. Winter Landscape in Moonlight thus stands not only as a peak of Kirchner’s creative output but also as a landmark in the history of modern art’s expansion of print techniques.

Conclusion

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Winter Landscape in Moonlight (1919) occupies a singular position at the intersection of personal trauma, technical daring, and poetic vision. Through its bold composition, electrifying color contrasts, and textured woodcut surfaces, the work encapsulates the tensions of its historical moment while offering a timeless meditation on solitude, resilience, and the power of nature. Kirchner’s innovative approach to the woodcut medium—his celebration of imperfection, his layering of multiple carved blocks, and his embrace of material texture—elevated printmaking to an art form equal to painting. As viewers continue to contemplate the scarlet sky, crescent moon, and silent chalet, they encounter not only a landscape but a mirror of human endurance. Winter Landscape in Moonlight endures as a radiant example of Expressionism’s capacity to transmute adversity into luminous art.