Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

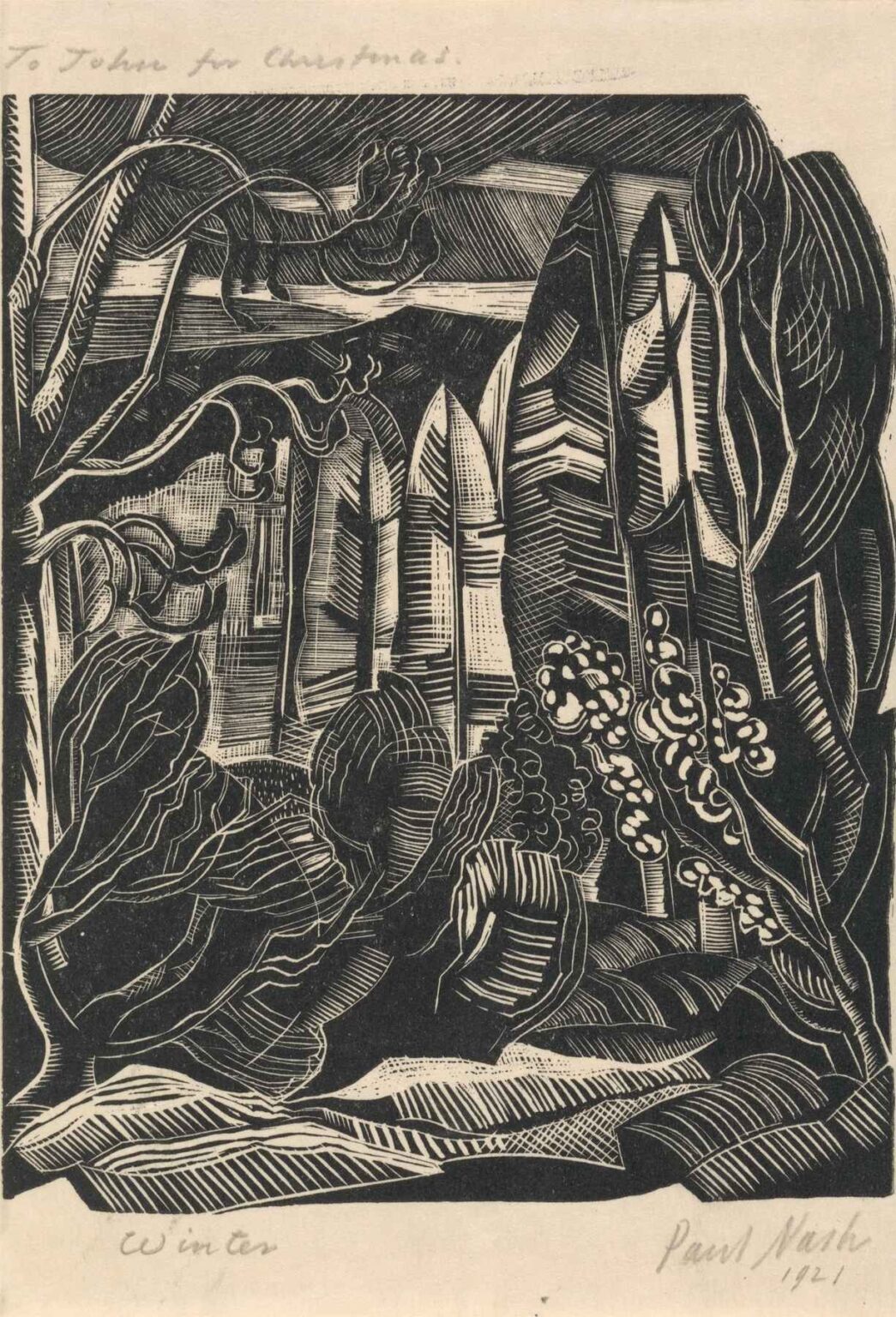

Paul Nash’s Winter, Hampden (1921) is a striking example of British Modernism fused with the introspective symbolism characteristic of the artist’s mature style. Rendered in stark black-and-white using the wood engraving technique, this work encapsulates Nash’s ability to distill landscape into rhythm, abstraction, and psychological resonance. Created during the post-World War I period, Winter, Hampden evokes more than seasonal chill—it reflects a moment of creative evolution, philosophical inquiry, and emotional reflection.

This analysis will explore the historical context of Winter, Hampden, Nash’s unique visual language, the symbolism embedded in the natural forms, the technical mastery of the wood engraving process, and the work’s lasting influence within 20th-century British art.

Paul Nash: The Artist and the Era

Paul Nash (1889–1946) is considered one of the most significant British artists of the early 20th century. Initially trained as a landscape painter, Nash gained recognition as an official war artist during World War I, where he produced haunting depictions of trench warfare and the ruined countryside. After the war, Nash’s style evolved from representational naturalism to a more abstract and symbolic visual language. Influenced by Surrealism, Cubism, and British landscape traditions, his work combined realism with poetic mystery.

By 1921, Nash had relocated to the Chiltern Hills near Hampden, Buckinghamshire—a region that became deeply embedded in his art. Winter, Hampden reflects both the physical environment of this new home and the emotional aftermath of the war. The scene is not simply a record of a landscape in winter, but a psychological and metaphysical meditation on place, memory, and seasonal change.

The Medium: Wood Engraving

Winter, Hampden was created using the wood engraving technique, a printmaking process where the artist carves into the end-grain of a hardwood block, allowing for fine detail and expressive linework. This medium had experienced a revival in early 20th-century Britain, notably through the efforts of artists associated with the Society of Wood Engravers.

For Nash, wood engraving was not merely a technical experiment but a way to explore the interplay between structure and atmosphere. The discipline required by the medium—its binary language of black and white, its emphasis on line and texture—suited Nash’s architectural approach to composition.

In Winter, Hampden, the use of wood engraving heightens the contrast between the soft forms of nature and the hard lines of human geometry. The overall visual impact is bold, graphic, and textural—inviting close scrutiny and slow contemplation.

Composition and Structure

The composition of Winter, Hampden is highly structured, yet filled with rhythmic energy. Vegetation dominates the foreground and flanks, with large, stylized leaves curling and layering over each other like frozen waves. The foliage forms a kind of organic curtain, drawing the viewer inward toward the more linear, architectural elements at the center and back.

In the middle ground, vertical forms—tree trunks, fence posts, or possibly stylized gravestones—stand like sentinels, introducing a rigid geometry that contrasts with the flowing forms in the foreground. Above, diagonal hatch lines evoke a dense canopy or perhaps even falling snow, though rendered with such abstraction that they suggest psychological rather than meteorological phenomena.

A dark archway or structure cuts across the upper section of the image, creating a sense of enclosure or retreat. This could symbolize the transition from one state to another—from autumn to winter, life to death, or outer world to inner world. Nash’s interplay between light and shadow here is especially poignant, with white lines etched into black space to suggest illumination filtering through bare branches.

Nature as Symbol: Winter’s Psychological Landscape

In Winter, Hampden, nature is not passive but charged with emotional and symbolic weight. The season of winter—often associated with dormancy, silence, and death—is here both literal and metaphorical. Nash was fascinated by the cyclical processes of nature, and winter, in particular, represented a threshold: a time of inward turning and latent energy.

The dense foliage in the foreground, though stylized, appears lifeless, tightly curled and static. This vegetation, caught between growth and decay, mirrors the emotional stasis often associated with the post-war period. There is a sense of paused vitality, of potential trapped beneath a frozen surface.

At the same time, the careful design of the plants, their exaggerated veins and edges, imbues them with dignity and formality. They are not merely dying—they are monuments in a natural cathedral. This treatment elevates the mundane to the mythic, transforming the landscape into a site of ritual and reflection.

Line, Texture, and Rhythm

One of the most compelling aspects of Winter, Hampden is its intricate use of line. In wood engraving, the carved white lines are the negative space—the light—and Nash manipulates them with extraordinary finesse. The curved, concentric patterns in the leaves echo natural growth while also suggesting containment or compression.

Parallel hatchings evoke texture but also movement. The rhythmic linework in the upper background seems to radiate energy, as if invisible forces are active beneath the surface. This is a hallmark of Nash’s mature style—an interest not just in the appearance of the landscape, but in its hidden life and animating spirit.

The visual rhythm created by the repetition of shapes—leaf blades, vertical lines, tendrils—creates a musicality in the image. Like a fugue or a chant, the forms build and recede, moving the viewer’s eye across the page in a contemplative dance.

Influences and Style

Stylistically, Winter, Hampden reveals Nash’s engagement with both tradition and modernity. The use of flattened perspective and stylized forms suggests familiarity with Cubism and Vorticism, while the deep sense of place and reverence for nature connects Nash to the English Romantic landscape tradition of William Blake, Samuel Palmer, and John Constable.

In terms of technique, Nash’s wood engraving work aligns with contemporaries like Eric Gill and Gwen Raverat, who sought to revitalize the medium as a vehicle for personal and poetic expression. Yet Nash brings a unique quality to his prints: an introspective, sometimes mystical vision of the landscape that stands apart from mere illustration.

His interest in pattern, repetition, and symbolic form also links him to the emerging field of abstraction, particularly in the 1930s. While Winter, Hampden is not fully abstract, it pushes the boundary between representation and design in compelling ways.

Post-War Reflection and Landscape as Memory

Although created in 1921, three years after the end of World War I, Winter, Hampden cannot be fully separated from the context of the war and Nash’s role as a war artist. His experiences on the Western Front had a profound and lasting impact on his worldview. Nature, once seen as a source of comfort and inspiration, became a site of loss, memory, and transformation.

In Winter, Hampden, the absence of human figures intensifies the sense of solitude and introspection. The landscape is deserted, yet not empty. It bears witness to a passage of time, perhaps even mourning. The ordered yet mournful mood of the print echoes Nash’s paintings like We Are Making a New World (1918), where destruction is embedded in the landscape itself.

Hampden, as a specific location, represented for Nash a personal retreat—a sanctuary for rebuilding and quiet study. Yet even here, the specter of war and memory linger. The stark beauty of winter becomes a metaphor for endurance and regeneration.

Interpretation: Between Realism and Dream

Winter, Hampden exists in a liminal space between realism and dream. It is grounded in observation—of trees, leaves, snow—but reassembled through artistic imagination. This gives the print an otherworldly quality, as though it depicts not a literal landscape but the memory or essence of one.

The exaggerated curves, the rigidity of the vertical forms, the dramatic contrasts of black and white—all suggest a heightened emotional state. Winter is not just a season; it is a mood, a threshold, a state of being.

For viewers, the image invites personal interpretation. It may speak of isolation, clarity, mourning, or the quiet beauty of stillness. Nash’s refusal to dictate a single meaning allows the work to remain open, vital, and resonant across time.

Legacy and Influence

Winter, Hampden is a key example of how Paul Nash transformed British landscape art in the 20th century. His ability to merge technical innovation with deep emotional and symbolic content helped redefine the role of the landscape in modern art. This print, while small in scale, is monumental in its ambition and sophistication.

Nash’s influence can be seen in the work of later British artists such as Graham Sutherland, John Piper, and even contemporary land artists who explore similar themes of place, memory, and the unseen forces within nature.

Moreover, Winter, Hampden stands as a landmark in the history of modern printmaking. It demonstrates the expressive potential of wood engraving not just for illustration, but for serious, standalone works of art.

Conclusion

Paul Nash’s Winter, Hampden is far more than a seasonal landscape—it is a meditation on transformation, solitude, and the quiet power of nature. Through masterful use of line, texture, and contrast, Nash creates a visual poem that speaks to the emotional and spiritual dimensions of winter.

The work stands as a testament to Nash’s brilliance as a Modernist visionary and as a deeply personal interpreter of the English landscape. It reminds us that even in the stillest moments, the world is alive with hidden rhythms and unspoken memories.

Whether viewed through the lens of post-war reflection, artistic innovation, or environmental reverence, Winter, Hampden remains one of Paul Nash’s most evocative and enduring achievements.