Image source: artvee.com

Introduction to Henri Matisse’s “White Algae on a Red and Green Background” (1947)

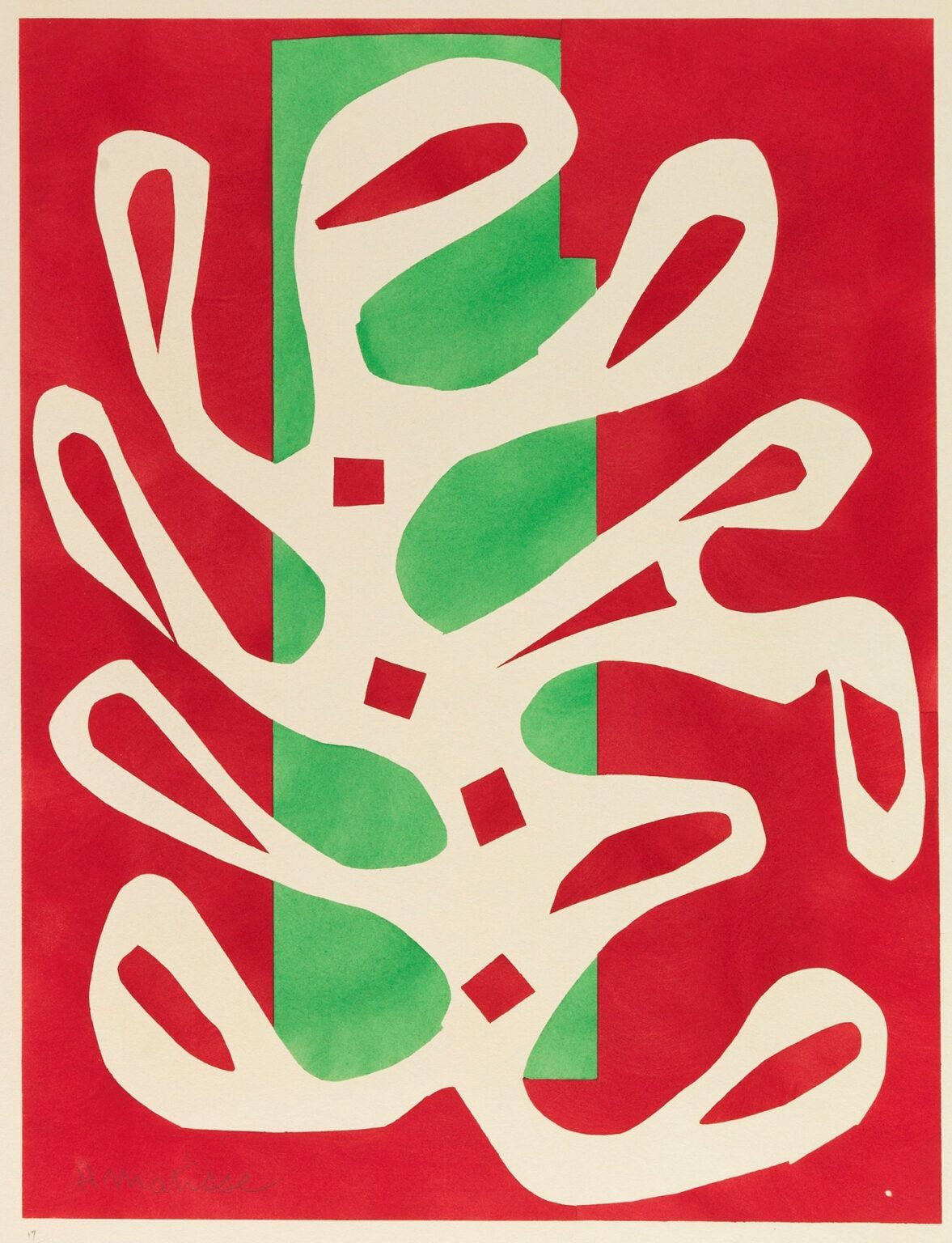

“White Algae on a Red and Green Background” is Matisse’s late style boiled down to its most essential elements: a bold field of color, a single organic form cut from paper, and the exhilarating clarity that arrives when everything unnecessary has been stripped away. A looping white shape—at once plant, coral, ribbon and dance—sprawls across a warm red ground. A vertical bar of green rises behind it like a reef or stem, peeking through the open spaces inside the white form. The image is made from painted papers cut with scissors and arranged into a perfectly balanced composition. Nothing is shaded, modeled, or outlined; everything is decided by edge, interval, and the push-pull of complementary color. The result is a picture that reads instantly across a room yet rewards careful attention with a wealth of rhythmic detail.

The Late Cut-Outs and the 1947 Moment

By 1947 Matisse had reinvented his process. After serious illness, he exchanged long sessions at the easel for a radically flexible studio practice: sheets of paper brushed with opaque gouache, then scissored into shapes and pinned to the wall. He called it “drawing with scissors.” This new method let him work at scale, edit without penalty, and compose with color in its purest state. The year also coincides with the publication of his landmark book “Jazz,” where saturated color and simplified silhouettes set the template for the next decade of his production. “White Algae on a Red and Green Background” belongs to this period of concentrated invention. It is a laboratory piece and a fully realized artwork at once, demonstrating how far the cut-out language can go with only three colors and a single biomorphic figure.

Technique: Gouache, Scissors, and the Intelligence of the Edge

The cut-out’s force begins in its materials. Matisse first saturated sheets of paper with gouache, achieving a flat, matte color that holds light evenly. He then cut forms directly, without preparatory drawing. The scissors act like a continuous line—the kind of unbroken arabesque he had chased in ink and charcoal for decades—only now the line is an edge that carries shape and color simultaneously. You can feel the certainty of those cuts in the long, elastic loops and in the occasional squared turn where the scissor blades pivoted. The picture’s energy comes from those edges: crisp where the white meets red, softened where the green rectangle peeks through, and lively everywhere the form doubles back on itself.

Composition: A Living Form in a Clear Field

The white “algae” sprawls diagonally from lower left to upper right, looping into pods that resemble leaves, fronds, or the lobes of sea plants. These loops are not repetitive; each has a slightly different proportion and tilt, so the form never stiffens into pattern. Four small red squares embedded in the white body act like nodes or seeds. They punctuate the movement and calibrate the internal spacing, keeping the eye from racing through the open areas too fast. Behind the organism stands a vertical green slab slightly off-center. It plays multiple roles: a stabilizing spine, a backdrop that cools the composition’s temperature, and a complementary foil that makes the red surrounding field beat more strongly. The whole arrangement reads as a poised asymmetry—the modern equivalent of a classic figure-in-field scheme.

Color Strategy: Complementary Chords with a White Soloist

Matisse builds the image on the red–green complement, the most charged pair in the painter’s toolkit. The deep, festive red radiates warmth and makes the green sing brighter; the green, in turn, cools and organizes the space. Into this duet he inserts a third “color”: the untouched white of the cut form. In the late work, white is never a mere absence; it behaves like active light. It lifts from the surface and seems to hover above the red. Because the white spans the whole field, it turns the red and green into environment while it becomes protagonist. The tiny red squares set into the white body reassert the primacy of the ground and prevent the figure from floating free. The color harmony is simple, but it is orchestrated with the precision of chamber music.

Movement, Rhythm, and the Eye’s Path

The composition dances. The white shape begins in a tight coil at the bottom, unfurls into broader loops, and then narrows again near the top, like a phrase that swells and resolves. Each loop is a “beat” in a rhythm that travels diagonally and then rebounds on itself. Because the green bar runs straight up, the eye has a counter-tempo to play against the roving white. Those small red squares are syncopations—surprising hits that keep the beat lively. The viewer’s gaze traces the edges, slips into the openings, touches the green, and returns to the red, over and over. The picture is static only in the sense that it is complete; its inner movement is perpetual.

Negative Space as Positive Form

Matisse’s most radical late discovery is that empty space can carry as much form as the paper that frames it. In “White Algae on a Red and Green Background,” the open interior shapes of the white figure have the clarity of objects. They are not accidental voids but sculpted pockets of red and green that breathe through the composition. Notice how some openings align with the green bar, creating a sensation that the plant is tethered to a stalk or illuminated by a shaft of water. The negative spaces do narrative work—suggesting depth, attachment, or translucency—without the picture ever abandoning its flatness.

Organic Imagery: Sea, Garden, and Body

Matisse called the motif “algae,” and the name matters. It nudges the viewer toward the sea: tidal pools, drifting fronds, the soft drag of water on a plant. But the drawing also feels like garden leaves, the branching of a vine, or the lobes of a human figure abstracted to pure gesture. Matisse’s organic forms are deliberately multivalent. They belong to nature broadly and to the body indirectly. This ambiguity is a strength. It allows the picture to appeal to memory and sensation—salt water, sunlight, a walk in a conservatory—without binding it to one story.

Scale and Physical Presence

Even when reproduced small, the cut-out reads with billboard clarity. Viewed at original size, the white figure can seem almost life-size, a presence that shares the viewer’s space. The generous scale contributes to the work’s calm; the large loops are not fussy ornaments but confident spans of form. At this dimension, the hand-cut edges show tiny variations and the green rectangle reveals subtle brush-marks from the gouache—human traces that keep the surface alive within its radical simplicity.

Process: Pinning, Rearranging, and the Final Fix

The late cut-outs were composed on the wall with colored pins. Matisse and his assistants would move parts repeatedly, testing intervals and angles until the whole “rang true.” In a work like this you can imagine the choreography: the green bar shifted an inch to the left, a loop trimmed, a square repositioned to sharpen the diagonal. Only when the balance felt inevitable were the pieces glued down or translated into print by hand-stenciling. That working method explains the image’s musical rightness; it has been tuned by eye and body in real space, not sketched and tightened at a desk.

Relation to “Jazz” and the Decorative Ideal

“White Algae on a Red and Green Background” stands in close company with the plates for “Jazz,” published the same year. In both, Matisse treats the page like a theatrical backdrop on which silhouettes perform: swimmers, acrobats, foliage, and stars reduced to color and edge. The “decorative” in this late vocabulary is not ornament for ornament’s sake; it is a principle of coherence across a surface. The picture holds together like a woven textile or a panel of stained glass. Everything belongs because everything is constructed from the same logic: flat color, clear shape, rhythm in the intervals.

The Psychology of Clarity

Viewers often describe the late cut-outs as joyful. Part of that feeling comes from chroma—the straightforward pleasure of saturated color. But much of it comes from clarity. The work asks almost nothing of the mind in terms of decoding; recognition happens at once. That instant legibility frees attention for subtler pleasures: how the loops widen and narrow, how the red squares pull the white back to the ground, how the green bar cools the heat. In a century of complexity and upheaval, Matisse offers an image that restores order without denying energy.

Modernity and Timelessness

Although made in 1947, the picture looks startlingly contemporary. Its flat fields, crisp edges, and graphic punch feel at home in today’s design culture; at the same time, its organic loops connect it to ancient ornament and plant forms seen in every epoch. That fusion of modern means and timeless motif gives the work its durable appeal. It reads as both new and inevitable.

Material Honesty and the Beauty of Simplicity

Matisse’s cut-outs never hide what they are: paper, paint, and scissors. The honesty of those materials is part of their beauty. Light sits on the gouache with a soft, even glow; the paper’s thickness makes a tiny shadow where shapes overlap; the scissor’s path leaves small, human deviations in the edge. In a world where images can be endlessly manipulated, the directness of this construction feels refreshing. It reminds us that powerful art can come from very few ingredients, perfectly chosen.

How to Look: Three Passes Through the Picture

The work rewards three kinds of viewing. First, take it in from across the room and register the big chord—white movement on red heat cooled by green. Second, move close and study the edges: the tiny notches, the curve’s changing speed, the way openings are calibrated to the green behind. Third, soften your focus and let the image settle as a single rhythm. You will feel the composition’s timing in your breath: swell, release, swell, release.

A Bridge to the Monumental Late Works

This cut-out anticipates the great decorative panels of Matisse’s final years: large sheaves of leaves, swimmers, ivy, and blue figures spread across walls and chapel windows. The same principles are at work—complementary color, enlarging of the arabesque, and a near-architectural sense of placement. “White Algae on a Red and Green Background” reads like a concise study for that larger ambition, a portable manifesto declaring that color, edge, and rhythm are enough to build a world.

Why “White Algae on a Red and Green Background” Matters

The piece matters for more than its beauty. It encapsulates an argument about what painting (and picture-making more broadly) can be after the crises of the first half of the twentieth century. It says that representation can be reimagined as relation—of color to color, shape to shape—and that feeling can travel through the most economical means. It says that the decorative is not trivial but foundational, the very logic by which a surface becomes coherent and pleasurable. And it says that an artist in late life can invent a second youth of form, as fresh as anything made before.

Conclusion: A Single Shape, A Complete Harmony

In “White Algae on a Red and Green Background,” Matisse composes with the confidence of someone who knows exactly what he wants a picture to do. A white organism unfurls like a calm dance, red and green fields hold the stage, and four small squares set the tempo. There is nothing superfluous, nothing timid. The image is both immediate and contemplative, graphic and humane. It clarifies the promise at the heart of Matisse’s late career: that clarity, rhythm, and color—handled with intelligence—can carry all the feeling a modern picture needs.