Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

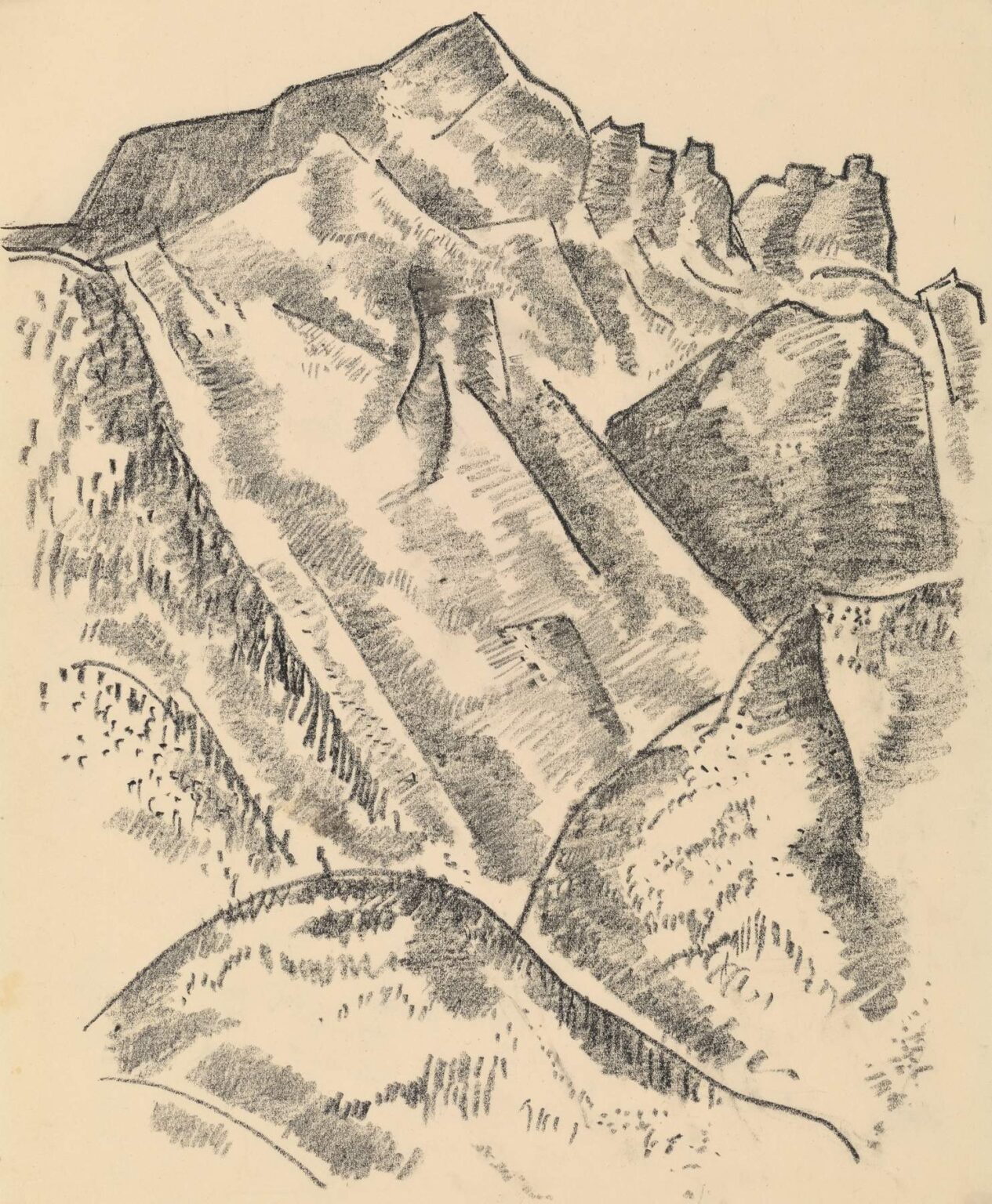

Marsden Hartley’s 1933 drawing “Waxenstein” presents a powerful meditation on the intersection of natural grandeur and modernist restraint. Rendered in charcoal or graphite on paper, the work strips away color to focus intently on form, texture, and tonal interplay. A series of towering peaks, rendered with assured strokes and delicate shading, rises from a darkened foreground, their summits dissolving into an expanse of blank sky. At first glance, the viewer is drawn to the dramatic silhouettes, but a closer inspection reveals Hartley’s meticulous attention to geological contours and the subtle gradations of light upon craggy surfaces. Rather than a documentary topographical study, “Waxenstein” transcends mere representation—it becomes a vessel for emotional resonance and spiritual reflection, inviting the observer to contemplate both the materiality of the mountain and its symbolic weight.

Historical and Biographical Context

By the early 1930s, Hartley had already journeyed widely through Europe, absorbing influences from German Expressionism, the spiritual landscapes of the Alps, and the geometric rigor of the Bauhaus school. His travels took him to the Bavarian Alps, where he encountered the massif of Waxenstein—an area that evoked both the sublime traditions of Romantic mountain painting and the forward-looking ethos of interwar modernism. At this stage in his career, Hartley was grappling with personal loss, spiritual inquiry, and a shifting sense of identity amid the tumult of the interbellum period. The Great Depression had also reshaped the cultural landscape in America, prompting artists like Hartley to seek solace and meaning in nature’s elemental forces. “Waxenstein” thus emerges at the confluence of personal, historical, and artistic currents, reflecting Hartley’s ambition to distill profound emotional content through formal reduction.

Visual Overview

In “Waxenstein,” three principal peaks dominate the composition, their masses articulated through a complex interplay of light and shadow. The central peak, broad at its base and rising to a flattened apex, commands the scene, while subsidiary ridges to left and right recede into space. Hartley employs varied mark-making techniques—short, expressive strokes indicate rough rock faces, while softer smudges suggest weathered slopes and drifting snow patches. The foreground is rendered in deep, uniform shading, serving as a visual anchor that grounds the monumental forms. Above the peaks, the sky remains unmarked, creating a visual counterpoint that heightens the mountains’ sculptural presence. This stark juxtaposition of positive and negative space imbues the drawing with both simplicity and drama.

Composition and Structure

Hartley’s careful structuring of “Waxenstein” relies on principles of balance and dynamic tension. The triangular arrangement of peaks establishes a stable yet ascending movement, guiding the viewer’s gaze upward along an implied diagonal axis. The lower left slope, painted in broad, dark strokes, creates a visual ramp that leads the eye toward the highest summit. Negative space above and between peaks allows the forms to breathe, preventing the composition from feeling crowded. This interplay between mass and void recalls classical notions of pictorial equilibrium, yet Hartley subverts them through reductive means—eschewing decorative detail in favor of pure volumetric expression. The result is a composition that feels both timeless and resolutely modern.

Line Quality and Textural Treatment

Line in “Waxenstein” plays a dual role: it delineates the mountains’ outlines while simultaneously suggesting textural variety. Hartley’s outlines are assertive yet varied in weight, thicker where ridges protrude and thinner at points of receding plane. Within these contours, short hatch marks and stippled patterns evoke the varied surfaces of rock, scree, and snow. In places, the marks are dense and energetic, conveying jagged cliff faces; in others, they are sparse and gentle, implying rounded, weathered slopes. This nuanced approach to texture imbues the drawing with tactile immediacy, inviting the viewer to sense the mountain’s rugged surfaces. Hartley’s mark-making thus becomes a form of visual poetry, each stroke contributing to a rich tapestry of material presence.

Tonal Variations and Light

Without the distraction of color, “Waxenstein” relies on tonal variation to convey volume and mood. Hartley achieves a full tonal spectrum, from the velvet darkness of the foreground to the luminous highlights on sunlit ridges. These highlights, rendered with minimal but deliberate smudging and erasure, punctuate the composition and draw attention to key structural elements. Midtones, applied through broad, even shading, articulate large expanses of slope, while sharper tonal contrasts define cliff edges and shadowed recesses. The interplay of light and shadow is both naturalistic and evocative: it suggests a specific time of day—perhaps early morning light grazing the peaks—while also serving as a metaphor for revelation and concealment. In “Waxenstein,” light is not merely descriptive but imbues the form with spiritual resonance.

Spatial Depth and Perspective

Hartley’s handling of depth in “Waxenstein” is subtle yet effective. The central peak’s assertion in the picture plane is counterbalanced by the receding ridge on the left, whose hazier edges imply atmospheric distance. The dark foreground acts as both a physical platform and a pictorial threshold, enhancing the illusion of three-dimensional space. Hartley avoids rigid linear perspective; instead, he relies on overlapping forms and decreasing detail to suggest recession. The spatial ambiguity created—where specific distances remain indeterminate—enhances the drawing’s universal quality. Rather than anchoring the viewer in a precise locale, the work evokes an archetypal mountain realm, one that can stand for any lofty summit encountered in human imagination.

Emotional Resonance and Atmosphere

“Waxenstein” resonates on an emotional level through its austere beauty and contemplative stillness. The viewer is invited into a silent world, where the tactile textural marks and strong tonal contrasts evoke both the physical power of geological mass and a hushed, meditative atmosphere. The blank sky above the peaks amplifies this stillness, suggesting infinite space and inviting introspection. Far from a dramatic storm scene or romanticized rearing of clouds, Hartley’s mountain is serene yet formidable—an enduring presence that both humbles and uplifts the observer. By stripping the scene to its elemental components, Hartley offers a form of visual meditation, one that encourages the viewer to confront the sublime without distraction.

Symbolism and Interpretation

Mountains have long served as potent symbols of spiritual ascent, personal challenge, and transcendence. In “Waxenstein,” Hartley channels this heritage but reframes it through his modernist lens. The sheer simplicity of form suggests universality: this is not merely a portrait of one peak but a distilled emblem of the mountain as an idea. The hardened ridges and deep shadows speak to resilience in the face of adversity, while the luminous highlights hint at moments of clarity and revelation. For Hartley, whose work often explored themes of identity, loss, and renewal, the mountain can be seen as a stand-in for the artist’s own journey—each ridge a milestone, each summit an aspiration. In this reading, “Waxenstein” becomes a self-portrait of endurance.

Relation to Modernist Movements

While “Waxenstein” evokes the Romantic legacy of Caspar David Friedrich and Albert Bierstadt, it also engages with contemporary modernist currents. The reductive geometry of the peaks recalls Cubist interests in deconstructing form, while the expressive line work nods to German Expressionism’s emphasis on emotional content. Yet Hartley avoids overt abstraction or distortion; his goal is synthesis rather than fragmentation. By distilling the mountain’s form to essential volumes, he aligns with the Bauhaus pursuit of functional clarity, even as he maintains a deeply personal, expressive register. “Waxenstein” thus occupies a unique position at the nexus of tradition and innovation, demonstrating Hartley’s ability to absorb diverse influences into a coherent, singular vision.

Technical Execution and Medium

The tactile quality of the drawing suggests the use of charcoal and graphite, possibly combined with lithographic transfer techniques. Hartley’s handling of the medium exhibits remarkable control: the smudges and erased areas required a deft touch to maintain clarity of form, while the darker accents demanded a confident hand. The paper’s warm tone adds a subtle background hue that contrasts with the cooler grays of the charcoal, lending the work a soft visual warmth. This technical finesse underscores Hartley’s versatility across media—he was equally adept at oil painting, watercolor, and drawing—and demonstrates his continued exploration of how medium can shape meaning.

Marsden Hartley’s Artistic Evolution

“Waxenstein” emerges from a period of introspection and refinement in Hartley’s career. After the flamboyance of his early Fauvist-inspired works and the emotional intensity of his German period, he turned toward a more restrained, contemplative mode. His time in the Alps offered an opportunity to reconnect with elemental forces, and his subsequent drawings reveal a deepening interest in form and light rather than vivid color or overt narrative. “Waxenstein” encapsulates this shift: it speaks less of external anecdote and more of internal experience, translating the mountain’s immutable presence into a language of mark and tone. In doing so, Hartley reaffirms his place as a pioneer of American modernism, one who could weave personal introspection into broader aesthetic dialogues.

Waxenstein Within Hartley’s Oeuvre

Although Hartley’s mountain studies are less numerous than his portraits or abstract compositions, “Waxenstein” stands out for its austere power. It occupies a critical niche in his body of work, bridging his early European-influenced landscapes and the more abstract, symbol-laden paintings of his later years. Collectors and scholars often cite “Waxenstein” as evidence of Hartley’s capacity to engage deeply with natural forms without sacrificing formal rigor. Exhibited alongside color-saturated canvases, the drawing provides a moment of quiet contrast—a testament to Hartley’s restless experimentation and his belief in the mountain’s enduring metaphorical potential. In retrospective exhibitions, “Waxenstein” often serves as a focal point for exploring Hartley’s relationship to place, spirituality, and medium.

The Mountain as Metaphor

In “Waxenstein,” the mountain transcends its physicality to become a universal symbol. Its geometric mass evokes architectural solidity, while its weathered surfaces speak to endurance over time. The interplay of light and shadow reflects cycles of revelation and concealment, mirroring human experience. By presenting the mountain in monochrome, Hartley encourages viewers to look beyond surface idiosyncrasies and engage with the form’s intrinsic essence. The work invites contemplation of broader themes—strength in adversity, solitude as a path to self-discovery, the interplay of permanence and transience. In this sense, “Waxenstein” functions as both a landscape and a metaphorical map of inner terrain.

Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

Decades after its creation, “Waxenstein” continues to inspire artists and scholars alike. Its austere approach to landscape prefigures later minimalist tendencies, while its expressive mark-making resonates with contemporary drawing practices. In an era of environmental concern and renewed interest in human–nature relationships, the drawing feels particularly resonant: it reminds us of the mountain’s grandeur, its ecological significance, and its capacity to humble and elevate the human spirit. Museum exhibitions and academic studies often highlight “Waxenstein” as a key moment in Hartley’s evolution, and its presence in public collections ensures that new generations encounter its silent majesty.

Conclusion

“Waxenstein” by Marsden Hartley stands as a singular achievement in American modernism—a work that marries formal refinement with deep emotional resonance. Through carefully calibrated lines, nuanced textures, and a masterful tonal range, Hartley renders the mountain not merely as a physical landmark but as an emblem of transcendence, endurance, and spiritual inquiry. The drawing’s balanced composition, evocative atmosphere, and symbolic depth assure its place as a masterpiece of 20th‑century art. As viewers continue to engage with “Waxenstein,” they encounter not only a mountain’s timeless presence but also a reflection of the artist’s quest to distill nature’s grandeur into the essentials of form and light.