Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context: Van Gogh’s Final Months in Auvers-sur-Oise

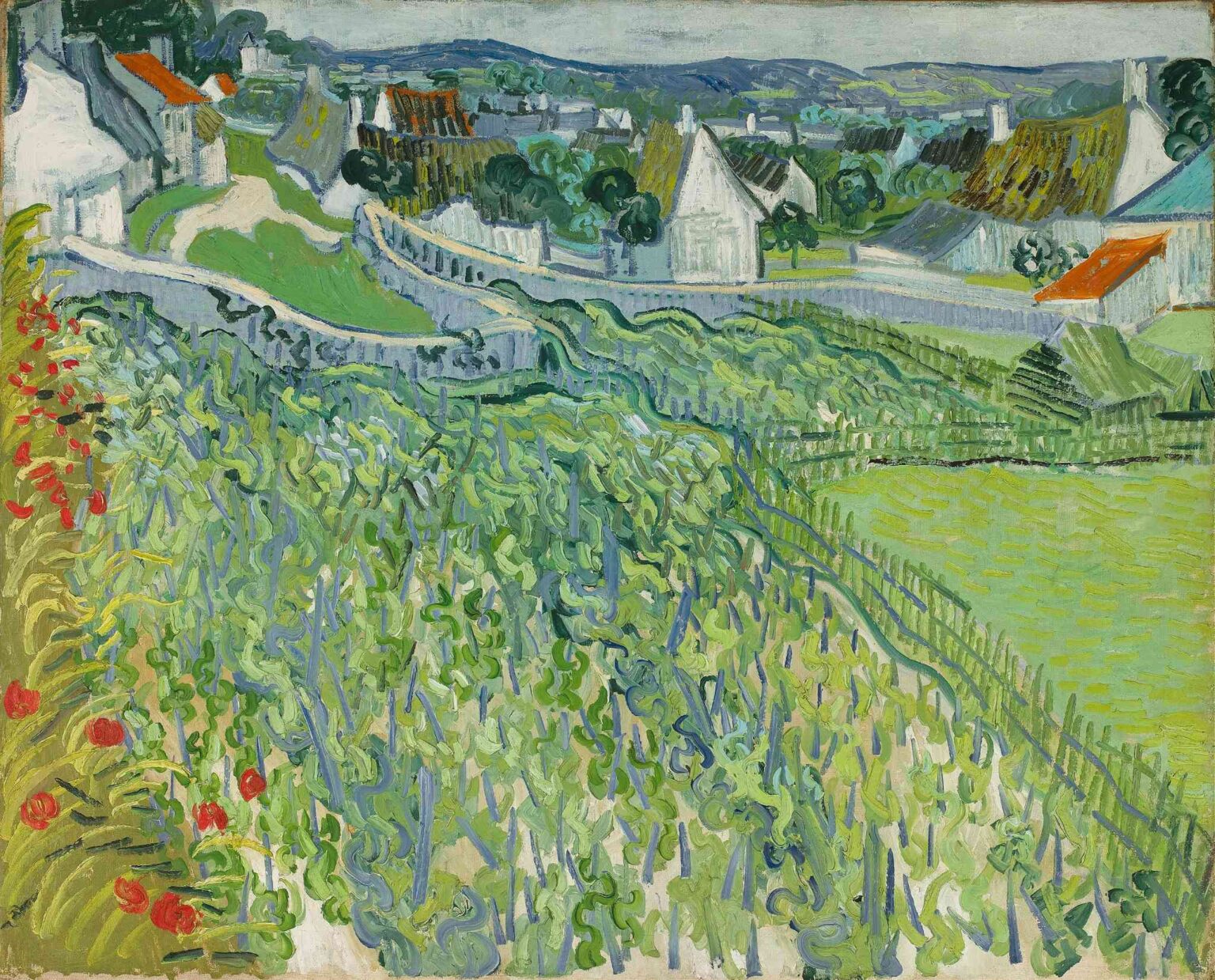

In May 1890, following a year of intense creativity at the Saint-Rémy asylum, Vincent van Gogh relocated to the village of Auvers-sur-Oise, just north of Paris. Under the care of Dr. Paul Gachet, Van Gogh embarked on a final creative surge, producing over seventy canvases in seventy days. His subjects ranged from church spires to wheatfields, from peasants’ cottages to the winding Oise River. “Vineyards at Auvers,” painted in June or early July 1890, reflects this period of effervescent output. The painting captures the cultivated vines that clung to the rolling hillsides around Auvers, offering Van Gogh—ever drawn to agrarian motifs—a new stage on which to explore his late-period style: bold color juxtapositions, animated brushwork, and a heightened sensitivity to light and atmosphere.

The Subject Matter: A Verdant Patchwork of Vines

“Vineyards at Auvers” portrays a hillside vineyard in full leaf, its rows of vines woven into a tapestry of greens, blues, and ochres. In the foreground, the vines march toward the viewer in undulating parallels, their trunks and canes rendered as rhythmic vertical strokes. Bright red hollyhocks or poppies cluster along the left margin, their warm tones contrasting with the cool foliage. Beyond the vineyard, a curving stone wall demarcates the cultivated land from a manicured lawn and the whitewashed cottages of Auvers perched along the ridge. The distant hills fade into pale lavender and gray, suggesting a summer haze. By focusing on both close-up vegetation and its broader setting, Van Gogh unites the intimate and the expansive, inviting viewers to contemplate vine and village as parts of a single living landscape.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Van Gogh arranges the scene along a sweeping diagonal from the lower right to the upper left. This diagonal organizes the vineyard rows, the stone wall, and the winding path that leads past the cottages. The foreground vines dominate, their sinuous lines breaking through the picture plane, while the middle ground settles into the orderly geometry of the wall and lawn. The background cottages and distant hills form horizontal bands, calming the composition’s momentum. Vertical accents appear in the vine stakes, tree trunks, and hollyhocks, counterbalancing the dominant diagonals. Through this interplay of directional forces, Van Gogh creates a living rhythm: the eye is drawn first to the lively vine rows, then guided upward toward the village, and finally rested on the tranquil horizon.

Palette and Light: Harmonizing Greens, Blues, and Warm Accents

In “Vineyards at Auvers,” Van Gogh employs a spring-to-early-summer palette of fresh greens, pale blues, and subtle yellows. The vineyard’s foliage ranges from deep viridian in shadowed rows to light chartreuse in sunlit leaves, often outlined in cobalt blue to heighten visual contrast. The lime-green lawn beyond the stone wall glows in midday light, while the white cottages reflect diffuse sunlight. Touches of madder lake and cadmium red punctuate the left margin through hollyhocks or poppies, providing vibrant focal points amid the cooler hues. The distant hills, painted in muted ultramarine and lavender, recede beneath a pale sky streaked with ivory and gray. Van Gogh’s color choices convey both the warmth of the season and the refreshing coolness of the vine canopy, achieving a dynamic but balanced harmony.

Brushwork and Texture: A Symphony of Directional Strokes

Van Gogh’s late-period technique is on full display in “Vineyards at Auvers.” Each element is built from short, energetic brushstrokes that echo the subject’s own movements: the vines’ twisting canes, the hollyhocks’ trembling blooms, and the stone wall’s rough surface. In the vineyard rows, Van Gogh applies thick impasto in vertical strokes to form vine trunks, while horizontal dashes suggest the tilled soil between them. The hollyhocks consist of curved, looping marks that evoke petal forms. The cottages are rendered in broader, more fluid strokes, their walls and roofs outlined with confident lines. Even the sky is alive with directional smears of light and shadow. Altogether, these strokes create a vibrant surface that captures the tactile essence of vine leaves and field soil, transforming paint into living matter.

Light, Atmosphere, and Seasonal Ambiguity

Rather than depicting a single moment of the day, Van Gogh evokes the general luminosity of a late‐spring or early‐summer afternoon. The absence of strong cast shadows suggests either an overcast sky or the soft diffusion of light through thin cloud cover. Highlights on leaves and lawns are achieved through impasto applied directly with the brush, catching gallery light and imparting a sense of shimmering air. Cooler tones in the vine crowns and distant hills counterbalance the warmth of sun-lit greens, creating an atmospheric depth. The painting’s combination of climatic freshness and gentle heat evokes the fleeting threshold between spring’s renewal and summer’s fullness, a temporal ambiguity that resonates with Van Gogh’s own transient hopes and anxieties.

Symbolism and Thematic Resonance

Vineyards carried layered meanings for Van Gogh. As symbols of cultivation and human partnership with nature, they represented the fruits of labor tempered by the cycles of growth, harvest, and dormancy. In Christian iconography, the vine often symbolizes spiritual nourishment and communal festivity—a motif Van Gogh, the son of a pastor, would have recognized. Here, the sturdy vines and vibrant hollyhocks embody resilience and vitality, while the stone wall and neatly kept cottages speak to order imposed upon the wild. Yet the painting’s gestural dynamism and shifting color fields remind us that all cultivation is provisional, subject to seasons, weather, and time. In this sense, “Vineyards at Auvers” meditates on the balance between human endeavor and nature’s overarching rhythms.

Relation to Van Gogh’s Other Auvers Landscapes

Painted within weeks of “Green Wheat Fields, Auvers”, “Wheatfield with Crows,” and “Thatched Cottages in the Garden,” “Vineyards at Auvers” forms part of Van Gogh’s final landscape suite. While wheatfields explore the tension between sky and earth, and cottages emphasize built form amidst greenery, vineyards fuse both approaches: the intimate vegetal close-up extends into the architectural and topographical expanse. The hollyhocks echo the flowerbeds in his 1883 Dutch works, yet here they stand amid new chromatic freedom. Together, these late canvases map Van Gogh’s relentless experimentation with perspective, color, and emotional tone—culminating in a singularly personal vision of the Auvers countryside that transcends mere naturalism.

Technical Examination and Conservation Insights

Scientific analysis of “Vineyards at Auvers” confirms Van Gogh’s use of lead white, chrome yellow, viridian, cobalt blue, and red lake pigments—consistent with his Paris and Arles periods. Infrared reflectography reveals minimal underdrawing, indicating the artist’s reliance on direct brush composition. Microscopic examination shows varied impasto thickness: the largest buildup occurs in the vine foliage and hollyhocks, while the stone wall and rooftops are executed in flatter passages. Conservation records note fine craquelure in heavily textured areas, typical of Van Gogh’s rapid application techniques. A recent cleaning removed yellowed varnish layers, reestablishing the painting’s original brilliance, particularly in the lime-green lawn and cobalt-blue outlines.

Provenance and Exhibition History

After Van Gogh’s death in July 1890, “Vineyards at Auvers” passed to his brother Theo and then to Theo’s widow, Jo van Gogh-Bonger. It featured in early retrospectives—Amsterdam 1892, Brussels 1893—and was acquired by a Belgian collector in the early twentieth century. The painting changed hands several times among private European collections before entering a major North American museum in the mid-1900s. Its exhibition in landmark Van Gogh retrospectives—particularly those focusing on his Paris and Auvers periods—has cemented its reputation as a key work for understanding the artist’s final evolution.

Critical Reception and Scholarly Perspectives

Early critics admired the painting’s fresh palette and rhythmic handling but sometimes regarded it as secondary to Van Gogh’s more dramatic Provence canvases. Mid-century scholarship reevaluated “Vineyards at Auvers” as a pivotal transitional work, demonstrating his fully assimilated color theory and the emergence of pure expressive brushwork. Psychoanalytic readings interpret the robust vines and blooming hollyhocks as symbols of resilience amid Van Gogh’s inner turmoil. More recent eco-critical studies explore the painting’s depiction of human-nature interdependence and its relevance to contemporary dialogues on sustainable agriculture. Across these lenses, scholars recognize “Vineyards at Auvers” as both an aesthetic triumph and a fertile field of interpretive possibility.

Legacy and Influence on Landscape Painting

“Vineyards at Auvers” continues to inspire landscape artists seeking to blend botanical detail with gestural freedom. Expressionist and Post-Expressionist painters cite its vibrant color contrasts and animated brushstrokes as foundational. Contemporary plein-air practitioners emulate Van Gogh’s compositional diagonals and his ability to convey seasonal light through pigment alone. In design and popular culture, imagery of vineyards often references Van Gogh’s idiosyncratic style—curvilinear vines, bold outlines, and luminous fields. As a touchstone for merging natural subject matter with personal expression, “Vineyards at Auvers” maintains its status as a masterclass in capturing the essence of cultivated landscapes.

Conclusion: A Harmonious Fusion of Cultivation and Expression

Vincent van Gogh’s “Vineyards at Auvers” stands as a culminating testament to his lifelong fascination with agricultural motifs and his late-period breakthroughs in color and brushwork. Through a masterful composition of diagonals, a balanced yet vibrant palette, and lively impasto, he transforms a simple hillside vineyard into a dynamic panorama of growth, labor, and seasonal renewal. Painted in the final days of his career, the canvas resonates with both serenity and underlying vigor—mirroring Van Gogh’s own interplay of hope and anxiety. As viewers wander among the painted vine rows and hollyhocks, they experience not only the Auvers countryside but the living spirit of an artist who saw in every cultivated field a reflection of the human journey.