Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

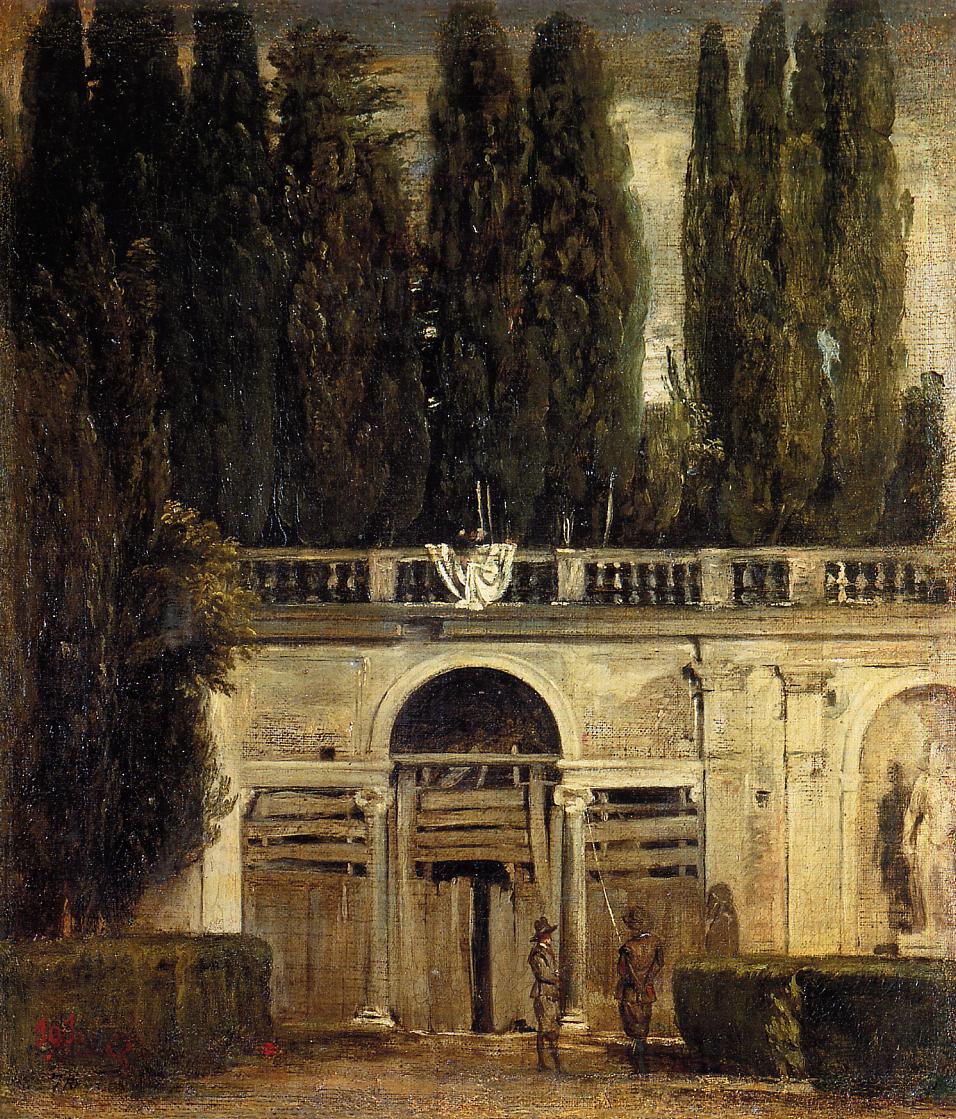

Diego Velázquez’s “Villa Medici in Rome (Facade of the Grotto Logia)” is a small painting with a large horizon. At first glance it seems an informal note taken in the garden: a pale arcade boarded up for repairs, two guards at ease beside clipped hedges, and a balustrade crowned by heavy cypresses that press upward into the sky. Look longer and the panel becomes a study in how light, air, and time shape architecture. Velázquez compresses the sensation of standing in front of the grotto loggia at the Villa Medici—smelling resin from the trees, squinting at sun on plaster, catching voices echoing beneath the arch—into a few inches of oil. This is the painter as attentive traveler, using a Roman subject to refine a language of atmosphere that would later support his grandest court scenes.

Historical Moment

Painted during Velázquez’s first Italian journey in 1629–31, the panel belongs to a tiny set of outdoor studies made at the Villa Medici. Rome offered him antique sculpture and Renaissance masters, but it also taught him the grammar of open air: how daylight flattens detail at noon and deepens it at dusk, how foliage swallows sound, how stone records seasons. Rather than produce a monumental veduta, he made intimate notes from life. These studies were not souvenirs; they were laboratories. The grotto loggia view registers the artist testing how swiftly he can fix a truthful impression without sacrificing structure—a question that would haunt European painting for two centuries.

The Site and Its Character

The grotto loggia sits on a terrace screened by hedges, its central arch flanked by smaller openings and crowned by a balustrade. At the time Velázquez painted it, the opening was boarded and braced as if under maintenance. Above the parapet, cypress trees rise like organ pipes, their dark verticals vibrating against the pale sky. The place is both garden and stage: a spot designed for coolness and display, where sculpture, water, and shade conspire to make a Roman afternoon bearable. Velázquez renders that dual identity—nature drilled into order, architecture softened by air—with sympathetic clarity.

Composition and Pictorial Architecture

The composition is built on steadfast symmetry and measured interruption. The central arch anchors the painting, a near-perfect semicircle whose dark mouth is shuttered by slats. Two lesser arches balance it, but Velázquez refuses strict mirroring; patches of plaster, repairs, and stains interrupt the rhythm so the facade feels lived-in rather than diagrammatic. A clipped hedge frames the bottom edge like a stage apron, ushering the two staff-bearing figures into the picture. Above, the balustrade runs as a cool horizontal, only once broken by a lump of drapery hung to dry. The dark cypresses form a second tier of verticals, their varied crowns keeping the top of the panel from hardening into a straight line. Everything aligns around the central void, yet every element retains its own tempo.

Light and Atmospheric Logic

The light is unmistakably Roman: chalky, high, and exacting. It falls broadly from the right, describing the columns as cylinders with a few unlabored strokes and throwing short shadows that hug their bases. The boarded arch is subdued, its slats absorbing light without drama, but the white lip of the arch catches a clean highlight that makes the curve ring. Across the balustrade, morning or late-afternoon illumination strikes the molded tops of the posts, while the cypresses swallow brightness into velvet. This measured distribution tells you the hour more convincingly than any clock. The air is dry and breathable; the transitions from light to shade occur in half-tones rather than in sudden cliffs of darkness, a hallmark of observation rather than studio invention.

Palette and Tonal Temper

Velázquez limits himself to greens, stony creams, and soft grays, with the warm tan of the ground peeking through to keep the surface alive. The facade reads as lime-washed plaster burned slightly by the sun; its color is not one flat recipe but a patchwork of warm and cool variations that echo real weathering. The trees are painted in a handful of greens that shift temperature with exposure—olive where sun catches the needles, bottle green where shade thickens. Sky is a pale, dry blue, as if pigment had been wiped thin to let the ground participate. The overall key is low and dignified. Nothing shouts; everything breathes.

Brushwork that Moves Like Weather

The panel is a lesson in doing much with little. Velázquez drags semi-dry paint across the facade to mimic the chalky drag of stucco. He strikes the cypress masses with short, broken touches that sit on the surface like clusters of needles, never dissolving into formlessness. The hedges are scumbled in darker, denser strokes, their squared tops achieved with two decisive passes rather than ornamental trimming. The guards’ uniforms are indicated by a few weighted notes: a hat brim, a gleam along a sleeve, the taper of a pike. Everywhere the brushwork assumes the viewer’s intelligence; it trusts that suggestion, when honestly calibrated, persuades more deeply than enumeration.

Architecture in a State of Becoming

The boarded loggia is more than a visual curiosity; it is the painting’s moral center. In a garden famous for its classical serenity, Velázquez chooses a facade interrupted by work. Wooden slats and props crisscross the void where visitors might expect sculpture and shadow. This makes the picture a meditation on maintenance and time. Even the most refined settings require care; even antique poise needs carpenters and clamps. The painter’s decision preserves a state between states—neither ruin nor perfection—giving the panel its distinctive modernity.

Figures as Instruments of Scale and Narrative

Two small figures stand near the central opening, pikes slanting across the facade. They are not true soldiers so much as custodians of decorum, embodied exclamation points in a sentence of stone. Their scale calibrates the architecture; without them, it would be difficult to feel the loggia’s human size. Their presence also shifts the mood from pure landscape to inhabited space. One figure seems to converse with the other, perhaps exchanging the slow gossip of an afternoon watch. Their lazy diagonals rhyme with the verticals of cypresses and columns, weaving people into the compositional fabric.

Depth, Interval, and the Rhythm of Space

The painting is shallow by design, a narrow proscenium backed by trees. Yet Velázquez creates interval by layering planar events. The hedge projects into our space, the figures occupy the immediate ground, the facade recedes a step, and the cypresses push hard against the sky. The eye walks through these tiers without strain because edges have been tuned carefully: the hedge is crisp at its top and soft at its sides; the columns are firm where lit and dissolve gently in shadow; the trees are feathery at their lit edges and dense within. This orchestra of edges makes space without resorting to linear perspective tricks.

The Intelligence of Edges

Velázquez’s control of edge is where his realism becomes poetic. The parapet’s highlight is drawn with a sure line that narrows toward the center, making the balustrade breathe. The cypress silhouettes are chiselled here and ragged there, imitating wind-flutter or uneven growth. The boarded arch takes a softer boundary against the darkness inside, avoiding the theatricality a sharp outline would bring. These shifts make the image feel observed rather than constructed, and they lend the facade the dignity of something encountered, not designed for a painting.

Sound, Heat, and the Senses Beyond Sight

Although nothing moves in the panel, it hums with implied sensation. You can almost hear cicadas in the trees and the dull knock of a pike butt on paving. The hedge suggests the cool smell of clipped greenery; the facade radiates heat back into the viewer’s face. These associations rise because the optical notes are correct: when light is right on stone and foliage, other senses rush in to complete the memory.

Comparison with the Other Villa Medici Views

In the companion garden study where an arched opening gives onto distant cypresses, Velázquez stages space as a walk through successive thresholds. Here he stages stillness under guardianship. The two paintings teach complementary lessons: one about recession and atmosphere, the other about planar solidity and the poetry of surface. Together they unveil a painter inventing a new genre for himself—small, direct encounters with places that hold history without demanding allegory.

Relation to the Broader Tradition

The facade study converses with the Venetian habit of painting architecture as light-catching stage and with Roman classicism’s love of measured order. Yet it avoids both the decorative sweetness of some Venetian vedute and the stiffness of archaeological record. Instead, Velázquez treats the loggia like a person sitting for a portrait—warts, repairs, and all—letting its character emerge from weathered surfaces and the discipline of looking. In doing so he anticipates later painterly studies by Corot and the oil sketches of Constable and lays a quiet foundation for the plein-air ambition of the nineteenth century.

Technique and Making

The panel likely began with a warm-toned ground over which Velázquez placed the big shapes in quick, thin washes. He then reinforced architecture with semi-opaque passages, saved the brightest whites for the parapet and column highlights, and tangled the cypresses with layered, broken strokes. The boards and props of the arch were probably drawn late, their darker values locking the composition’s center. Throughout he kept medium sparing, letting the weave of the support speak where stucco needed grain. The pace of the painting feels like an afternoon’s concentrated work, guided by sight rather than by studio recipes.

Ideas About Time Embedded in the Image

The boarded arch, the drapery flung over the balustrade, and the guards’ idle stance collect three different timescales. There is the quick time of a cloth hung to dry, the seasonal time of maintenance and repair, and the long time of cypresses growing and architecture standing. The painting lets these durations overlap without comment, trusting viewers to feel the coexistence of the transient and the durable. In that sense the panel is a philosophy of history written in sunlight.

What the Painting Meant for Velázquez

These Roman studies were not detours from grand history; they were calibrations of perception that enabled it. The confidence with which Velázquez later sets living bodies inside architecture—most famously in “Las Meninas”—owes much to the Villa Medici experiments. The way he distributes half-tones across flesh and stone, the discretion with which he sharpens or softens edges, and the conviction that the world’s plain surfaces can carry profound meaning all find rehearsal here.

The Viewer’s Journey Through the Panel

The eye enters along the hedge, meets the two figures, and slides to the boarded arch. It rests on the cool semicircle, wanders across the balustrade, pauses at the cloth, and then climbs the cypress columns to the pale roof of sky. Each stop is brief, each transition smooth, because Velázquez has tuned contrasts with musical care. The painting asks to be seen as one might stroll and linger in an actual garden: unhurried, attentive, receptive to small differences.

Enduring Modernity

For all its classical subject, the panel feels modern because it presents a fact of experience without narrative crutches. A facade under repair, two men on watch, trees and sky above—nothing more, nothing less. The claim to our attention is not theatrical but ethical: the world is worth looking at when the looking is honest. Many larger, louder pictures from the same decade have aged into history; this modest one still feels like weather passing in front of us.

Conclusion

“Villa Medici in Rome (Facade of the Grotto Logia)” is an essay in truthful seeing. Velázquez builds a world from a boarded arch, a run of balustrade, two quiet figures, and a screen of cypresses, then lets Roman light do the eloquence. The small scale makes the accomplishment clearer: with spare means and no rhetoric, he records not only how the place looked but how it felt to stand before it for an hour—the brightness of plaster, the depth of green, the patient geometry of architecture resisting time. What might have been a travel sketch becomes a compact statement about attention itself.