Image source: wikiart.org

Setting the Scene in the South: Matisse Arrives in Saint-Tropez, 1904

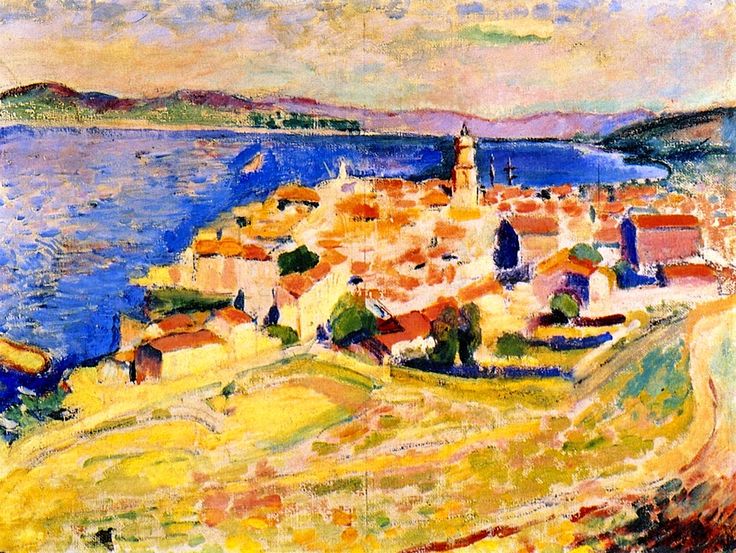

Henri Matisse’s “View of Saint Tropez” of 1904 captures the Côte d’Azur at the exact moment his art was shedding the last restraints of 19th-century naturalism and moving toward the audacity that would soon be called Fauvism. Painted from an elevated vantage on the hillside above the harbor, the picture takes in the town’s ocher ramparts, its scatter of red-tiled roofs, the vertical accent of the bell tower, and the intense, mineral blue of the Mediterranean. This is not a literal postcard. Instead Matisse builds the scene from brisk strokes of high-key color that record how the southern light feels, not simply how it looks. The view is recognizably Saint-Tropez, but the painting’s real subject is radiance.

Why Saint-Tropez Mattered to Matisse

The year 1904 is crucial in Matisse’s trajectory. In Saint-Tropez he absorbed the lessons of Paul Signac and other Neo-Impressionists who had settled along the coast to chase a purer light. Matisse experimented with Divisionist color—placing small strokes of unmixed pigment next to one another so that the eye blends them at a distance—while refusing the strict pointillist dot. His touch is freer, the marks larger and more varied. Saint-Tropez gave him a laboratory in which to test how broken color could carry structure, tone, and atmosphere all at once. “View of Saint Tropez” is among the clearest statements of that research: a sunstruck panorama organized not by exact drawing but by calibrated intervals of hue.

Composition from Above: The Hillside as a Natural Stage

The composition begins with the sweep of the pale, sun-blasted hillside at the lower right that curves like a ramp toward the town. This sloping foreground accomplishes three things. It establishes a tilted stage that energizes the whole picture; it bathes the scene in reflected yellow light; and it funnels the eye to the central cluster of roofs and the bell tower. From there the gaze moves left and out toward the sea, where the harbor’s cobalt plain stabilizes the composition with a wide horizontal. The distant headlands along the horizon act as a low parapet, preventing the eye from sliding off the canvas. Without resorting to rigid perspective, Matisse builds a dynamic promenade through the image, letting color zones—yellow, orange, green, blue—function as pathways.

Drawing with Color Instead of Lines

At first glance the painting appears loosely drawn, yet its forms are legible because Matisse uses color contrasts to do the work of contour. Roofs snap into place as warm red-oranges braced against cool lavender shadows. Streets materialize as cream ribbons edged by violet. The famous bell tower rises not because of a precise outline but because its warm ocher shaft is set against the snap of deep blue sea and the lilac of distant mountains. By making color carry the architecture, Matisse untethers description from line. This shift is foundational to the freedom of his later work: the world can be held together by relationships of hue.

A Palette Tuned to Mediterranean Light

The palette is pitched to the Mediterranean at noon. Sunlit walls read as lemon, straw, and pale peach; shadows are not gray but violet, turquoise, and cool green; the sea passes from cobalt to ultramarine with flashes of turquoise near the shore; red-orange roofs and pink trackways provide hot counterpoints to the marine cool. Rather than use black, Matisse darkens colors with their complements—violet against yellow, blue against orange, green against red—so that even the shadowed zones seem to vibrate. This complement strategy intensifies luminosity while keeping the surface breathable. The entire town seems constructed from pure daylight.

Touch, Stroke, and the Feel of Sun

Matisse lays paint in quick, directional strokes that echo the topography: lateral sweeps for the sea, short climbing dashes for the hillside, blockier touches for roofs, and stubby verticals for trees and cypresses. In places you can see him scumble a thin veil of one color over another, allowing underlayers to sparkle through like heat haze. The variety of touch gives different materials distinct identities—stone feels dry and granular, water dense and cool, vegetation elastic. Crucially, the touch is never fussy. The clarity of the scene comes from aggregation: dozens of confident marks collect into convincing forms. This is painting that favors decisions over details.

Light as the Architect of Space

Space in this picture is constructed chromatically rather than by strict perspective. Foreground yellows are saturated and thick; mid-distance houses are slightly cooled and thinned; mountains at the horizon are reduced to pale bands. The eye reads these temperature shifts as depth. Atmospheric perspective—the way distant forms cool and lighten—becomes a color scale Matisse manipulates with precision. The bell tower’s warmth pins it to the town; the sea cools into a vast plane that sits behind everything yet gleams forward through its intensity; the sky’s broken pastels sit lightest of all, a translucent lid over the scene. The result is a space you feel with your eyes rather than measure with a ruler.

The Bell Tower as Visual Axis and Civic Emblem

The vertical bell tower near the center is a fulcrum. It interrupts the horizontal force of the harbor and the diagonal sweep of the hill, providing an architectural note of steadiness within a composition animated by slants and ripples. Its position is not exactly central, which keeps the picture from becoming static. In terms of color, the tower is a warm torch amid surrounding cools, ensuring that the town’s civic heart is also the chromatic center. The choice is astute: viewers unfamiliar with Saint-Tropez still read that tower as the emblem of place.

The Sea as a Broad Field of Breath

Matisse treats the Mediterranean as a single, moving field. Instead of describing small waves or reflections, he varies the blue across width and depth: darker and denser near the left edge, lighter where the water catches the sky, and greener toward the shore. Tiny accents—a boat, a few vertical masts—are suggested rather than drawn, their minimalism keeping the expanse uncluttered. This broad plane of sea is more than scenery. It is the painting’s breath. Its coolness ventilates the hot town, and its calm horizontal stabilizes the diagonal pull of the land.

Rhythm and Repetition: Roofs, Trees, and Shadows

Look closely at the town’s interior and a rhythm reveals itself. Red roofs recur at uneven intervals, almost like musical beats. Between them, small green notes of cypress and umbrella pine rise and fall. Shadows, cast as streaks of lavender and blue, create a counter-rhythm that gives the streets direction. The painting’s vitality derives from these patterned alternations. It is not just a view; it is a cadence of sunlit shapes marching toward the sea.

The Courage to Simplify

One of the painting’s modern qualities is its refusal to narrate every brick and window. Large swaths of the hillside are allowed to remain washes of lemon and pale orange, enlivened by the texture of the canvas. Facades become simple planes set at different angles to the sun. Boats are abbreviated to slivers. This simplification is not laziness; it is a deliberate strategy to keep the eye on the essential sensation of light and heat. By withholding detail, Matisse invites viewers to complete the picture, and in that invitation lies the work’s contemporary freshness.

Lessons Borrowed and Transformed

Matisse’s months in the South brought him into direct contact with Signac’s color theories and the broken touch of Neo-Impressionism. But he diverges in key ways. Where strict pointillism forms an even optical mesh across the surface, Matisse lets stroke size expand or contract with the form being described. Where Signac often maintains a cool, analytic harmony, Matisse courts temperature extremes—hot yellows crashing into deep ultramarines—to heighten drama. And where many Divisionists construct space with almost architectural precision, Matisse allows the composition to tilt and sway slightly, reinforcing the bodily sensation of standing on a hillside under fierce light. The painting thus honors its sources while announcing an independent temperament.

The Psychology of Color Temperature

Color here does more than describe; it sets mood. The yellows of the hillside are not merely sunlight; they are warmth itself, the tactile memory of heat on skin. The blues of the sea suggest relief, depth, and distance all at once. The reds of the roofs supply energy and human presence. The lilac clouds read as warmth dissipating into evening, even if the scene remains largely a midday blaze. Because these temperatures are organized across the picture plane—warm land against cool sea, warm tower against cool sky—viewers sense a balance between shelter and openness, habitation and nature. Matisse composes an emotional climate as carefully as he composes a topographical one.

Movement Without Figures

There are almost no clearly rendered people in this view, yet the scene feels animated. Directional brushstrokes create a sense of traffic through the streets; the diagonal hillside draws the body downhill; the shifting blues of the water imply currents and breezes; the angled masts hint at boats rocking in the roadstead. The absence of figures is thus an advantage. Activity is generalized and continuous, not localized and anecdotal, which preserves the painting’s clarity.

The Role of the Canvas Surface

The painting’s brilliance relies on the surface as much as on color. Where Matisse spreads thin paint over the primed canvas, the tooth peeks through and flickers, adding a dry, sun-baked feel to the hillside. Where he piles pigment to describe roofs or the sea’s darker patches, the impasto catches light and seems to thicken the form. Throughout, the alternation of thin and thick, dry and glossy, behaves like another system of contrasts parallel to warm and cool. Surface becomes a second way of telling the story.

From This View to Fauvism

Within a year of this canvas, Matisse’s color would leap further in intensity at Collioure and the 1905 Salon d’Automne, where viewers encountered the shocking heat of his Fauvist palette. “View of Saint Tropez” foreshadows that break by establishing the main principles: color as structure, simplification of form, exaltation of local sensation, and a belief that a painting is a living field rather than a faithful transcript. You can already feel the Fauvist courage in the unmodulated yellows of the hill and the unapologetic ultramarines of the sea. The seeds of the revolution are here, germinating under the southern sun.

Reading the Painting Today

For contemporary viewers, the canvas offers a layered experience. On one level, it is a joyous panorama of a beloved coastal town. On another, it is a document of a historical pivot in European art. And at a more intimate level, it demonstrates how a painter can look at a complex place and choose a small set of decisive relationships—warm against cool, slant against horizontal, near against far—to make the complexity legible. Its optimism is earned. Matisse does not prettify; he clarifies. The picture’s clarity is why it still feels fresh more than a century later.

Focal Passages Worth Studying

Certain passages reward close attention. The thin, chalky lavender strokes suspended in the sky keep the high register from becoming sugary; they cool the heat rising from the land. The seawall on the far left is described with just a few darker blue strokes, enough to assert a hard edge against the water. The bell tower’s highlight—one small stroke of pale lemon—locks its geometry without resorting to linear drawing. A diagonal shadow that cuts through the hillside, painted in a mix of violet and green, quietly secures the tilt of the ground plane. These touches show Matisse’s economy: one carefully placed mark can do the work of many.

The Ethics of Looking

There is a generosity in the way this painting asks to be seen. It does not demand the viewer decode a symbol system or submit to a rigid perspective. It invites a slower pleasure: noticing how one color qualifies another, how the eye makes a roof from three strokes, how a town can be imagined from temperature differences. That generosity reflects Matisse’s larger ethic of painting: to create an art that brings calm and joy without sacrificing intelligence. “View of Saint Tropez” does precisely that.

A Coastal City Rebuilt from Light

Ultimately, the painting rebuilds Saint-Tropez from its light. The land is a set of warm mirrors reflecting the sky; the sea is a deep reserve of coolness pushing gently back; the town is the arena where the two meet in useful harmony. Matisse’s innovation is to let that harmony do the descriptive work. As a viewer you recognize roofs and streets and coastline, but what you really experience is a climate translated into paint. That translation is the achievement of 1904: a new language for seeing that will power the audacity of the years to come.