Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

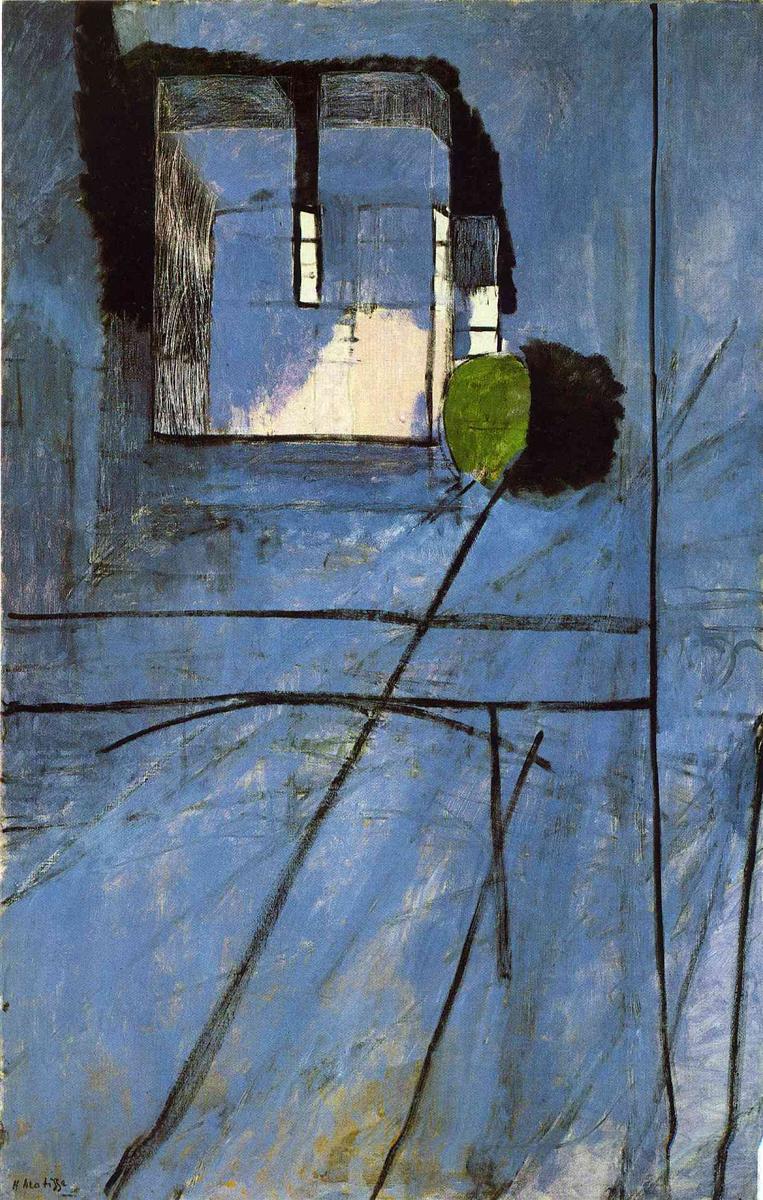

Henri Matisse’s “View of Notre Dame” (1914) is one of the most radical paintings in his long engagement with the window motif. From his studio on the Quai Saint-Michel, the artist looks toward the cathedral; yet what we receive is not a descriptive vista but a distilled structure: a cool blue field, a rectangular apparition of the façade, a few adamant black bars that stand for muntins and balcony rails, and a single rounded green shape that reads as a leafed tree or a cipher for life. With almost nothing in the way of detail, Matisse makes a full experience—interior and exterior, surface and space, memory and immediacy—vibrate within a single plane. The picture is both a view and an assertion that a painting is its own object, built from relations of color, line, and interval.

Historical Context

The canvas belongs to Matisse’s extraordinary pre–First World War year of 1914, a period in which he deliberately pared his language after the saturated revelations of Fauvism and the luminous order of his Moroccan travels. In works from this season—“French Window at Collioure,” “Woman on a High Stool,” “Gray Nude with Bracelet,” and “Interior with a Bowl with Red Fish”—he tests how little is needed to hold a picture together. “View of Notre Dame” is a keystone in that suite. The motif is familiar: a window in a studio, the city beyond. The treatment is new: the view becomes an arrangement of planes and edges that affirms the autonomy of the painted surface even as it evokes the world outside.

First Impressions

Seen from a distance, the painting reads as a large, cool-blue panel animated by a pale central rectangle and stitched by a few black lines. At the top center-left, a light façade sits within a dark surround—the cathedral simplified to a block of chalky light under a dark roofline. Vertical black bars announce the frame of the window; horizontal bars cut across the lower register like the shadow of a balcony rail. A single leaf-shaped green oval nests against a dark tuft, a compact note that arrests the flow of blue. The entire surface feels open and breathable, with thin scrapes and scumbles that keep the field alive. What first appears minimal quickly turns complex: the blue is many blues, the whites many whites, the lines various in pressure and intent.

Composition and the Architecture of the Window

Matisse organizes the composition as a cruciform of forces. The central rectangle of the cathedral holds the vertical axis; the lowest horizontal band, insistent and slightly off-level, secures the base. Additional horizontals arc or bend, hinting at the geometry of the balcony and the river’s sweep. At right, a long vertical boundary—perhaps the end of the wall—contains the plane while keeping the interior palpable. The rectangular apparition of Notre-Dame is framed by a dark band like a proscenium, reminding us that we are inside looking out. The small green oval, set just where exterior meets frame, operates as the pivotal accent, a hinge between constructed interior order and lived nature beyond.

Color, Temperature, and Tonal Architecture

The palette is sharply reduced yet richly tuned. The prevailing blue field ranges from slate to ultramarine to a smoky, violet-leaning tone, laid in dry, translucent veils that allow the canvas to breathe. Against that climate Matisse places a luminous white that stands for the sun-struck stone of the cathedral; around it a near-black roof silhouette and deepened window reveals sharpen the contrast. Black is not merely outline; it is temperature as well, cooling the adjacent blue and making the white vibrate. The single green note is saturated enough to register like a living thing—leaf, topiary, or emblem—and its warmth quietly counters the cooler blues without breaking the harmony. Color here is structural: blue sets the room’s air, white fixes the focal plane, black declares the edges, and green establishes life.

The Window as Idea and Object

For centuries painting was metaphorically a window onto the world. Matisse literalizes the metaphor and then interrogates it. He keeps the casement bars, the ledge, the wall seam—facts that make the interior present—while thinning the exterior to a light-filled slab and a roofline. The result is a view that admits its own framing. We can feel the thickness of the wall and the proximity of glass; we can also feel the claim of the surface, its refusal to dissolve into illusion. In this balance between opening and objecthood, “View of Notre Dame” states a modern credo: a painting can be at once a view and a thing.

Space Without Illusionism

Depth is conveyed through adjacency and value rather than through classical perspective. The light rectangle sits forward because it shines against a darker surround; the balcony bars cross in front of the field by virtue of opacity and line weight; the wall seam at right advances as a firm boundary. The blue expanse doubles as interior shadow and exterior air; the painting exploits this ambiguity to keep the surface unified. There is just enough recession to believe in a distant building; there is just enough insistence on flatness to make the painting own the room in which it hangs.

Drawing, Line, and Pressure

Line in this picture is a record of thought. The casement bars are laid with a loaded brush that leaves a dark ridge; the balcony’s horizontals are dragged more dryly, and their slight wavering registers the painter’s arm span. Thin, exploratory scratches—almost etched into wet paint—dart across the blue near the bottom, suggesting revisited placements or the tremor of reflected light. Around the cathedral shape, darker hatching knits the mass to its surround. The variety of pressure is the grammar of the painting: thick means certainty, thin means search, drag means atmosphere.

Negative Space and the Poetics of Omission

Matisse refuses detail. He does not render buttresses, statues, or tracery; he suggests windows with a short vertical slot, a crossbar, a narrow light. He does not spell out a river or bridge; he leaves angled traces that might be read as their proxies. These omissions are not signs of haste; they are instruments of clarity. By resisting the lure of description, he allows the simplest shapes—the rectangular light of the façade, the solid bars of the frame—to carry maximal meaning. Negative space becomes active; the untouched blue between lines reads as air and as interior shadow simultaneously.

The Green Oval

That single green oval is a linchpin. It reads first as a clump of foliage seen just beyond the balcony. Its location overlaps the window geometry and the dark tuft at the right, fusing space and surface. Chromatically it is the picture’s only major warm accent; compositionally it offsets the cathedral’s pale mass and stabilizes the right-hand side. Symbolically, the green stands for the world’s ongoing life amid the painting’s rigorous reduction. It is a quiet declaration that, even within severity, grace persists.

Time of Day and Weather

Though highly abstracted, the picture conveys weather: the blue field suggests early evening or a cool morning light that blue-shifts the room. The cathedral’s light block implies a sun-facing façade, bleached and bright, the kind of glare that washes detail. The dry scumbles at the bottom carry a hint of street dust and textured floor; the upper darks feel like the thick shadow of an awning or roof. Matisse records not meteorology but climate—a mood of cool air and pale shine that aligns with the painting’s emotional reserve.

Relations to “French Window at Collioure” and the 1914 Suite

“French Window at Collioure,” painted the same year, nearly cancels the view, turning the window into three vertical color planes and a diagonal wedge of floor. “View of Notre Dame” restores more of the outside world but in the same spirit of economy. Where the Collioure window asserts closure, this painting offers a permeable threshold; where the Collioure palette leans toward black-brown and acid green, here the blues and whites dominate. Together the canvases map Matisse’s inquiry into how a picture can be both decorative panel and lived experience.

Process, Revisions, and Surface Truth

Close looking reveals pentimenti—subtle ghosts where lines were shifted or wiped. The lower horizontals show earlier placements; the dark halo around the cathedral suggests that its edges were redrawn for balance. Scraped passages let previous layers speak through, keeping the blue from feeling monotonous. The material surface carries the history of decision, so that final clarity reads as earned rather than imposed. This candor about process is crucial to the painting’s modernity.

Scale, Bodily Address, and Viewing Distance

At human scale, the painting feels like an actual window; the bars meet the eye at roughly chest level, and the wall seam at right suggests the body’s proximity to architecture. The central light rectangle is large enough to register as a façade without minuteness. The viewer’s body is implicated—you stand before it as before an opening—and that bodily knowledge supplies much of the painting’s authority. From across a room the structure reads at once; at arm’s length the drag of the brush and the weave of the canvas become present, confirming the objecthood of the scene.

Rhythm, Ornament, and the Decorative Ideal

Though nearly abstract, the picture is deeply ornamental. The horizontals and verticals establish a measured grid; slanted underlines arc gently, creating a faint rhythmic counterpoint; the green oval acts as a medallion within the field. Matisse’s “decorative” is not mere embellishment but an ethics of balance—no single area dominates, and all parts contribute to the whole. Even the empty blue carries a light pulse through scumble and scratch, as if the surface were woven rather than painted.

Interpreting the View as Memory

“View of Notre Dame” also reads as a memory image, not of facts but of essential relations. The painting tells what most mattered in repeated looking from the studio: the regular assertion of the window bars, the pale shine of stone, the cool enveloping air, a dot of green life. Like a poem that omits conjunctions, the canvas strings nouns together and trusts the viewer to supply connectives. The result is not a snapshot but a durable mental map.

Influence and Afterlife

The painting’s discipline prefigures mid-century abstraction: Barnett Newman’s zips, Robert Motherwell’s bars, Helen Frankenthaler’s stained fields. Yet unlike many later canvases, Matisse anchors his reduction in lived perception; the picture remains a view before it becomes a pattern. Its logic of large planes and decisive edges also anticipates the cut-paper work of the 1940s, where windows and silhouettes become colored shapes pinned to a field. In museums today, “View of Notre Dame” still looks startlingly fresh because it speaks two languages at once—seeing and making—with equal fluency.

How to Look

Begin by letting the big relations settle: the light center, the cool surround, the black grid. Then follow each bar with your eyes, noticing where pressure increases and where the brush lifts. Linger at the green oval and feel how it balances the page; then drift upward into the pale façade and register the way small window slots suffice to conjure architecture. Step back until the painting locks as a view; step close until it returns to woven paint. Allow the surface to alternate between opening and object, understanding that this oscillation is the work’s true subject.

Conclusion

“View of Notre Dame” compresses a Parisian vista into a lucid arrangement of planes, lines, and one resonant accent of green. It is a view that stages the experience of looking rather than cataloging what is seen. The window does not simply frame a world; it becomes the painting’s grammar—vertical, horizontal, interval, and light. By refusing descriptive excess and trusting a few tuned relationships, Matisse achieves a rare equilibrium: the canvas is at once serene and alert, severe and generous, abstract and anchored in place. More than a century later, it continues to teach how a painting can breathe with almost nothing, provided that each mark is necessary and each color is just.