Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

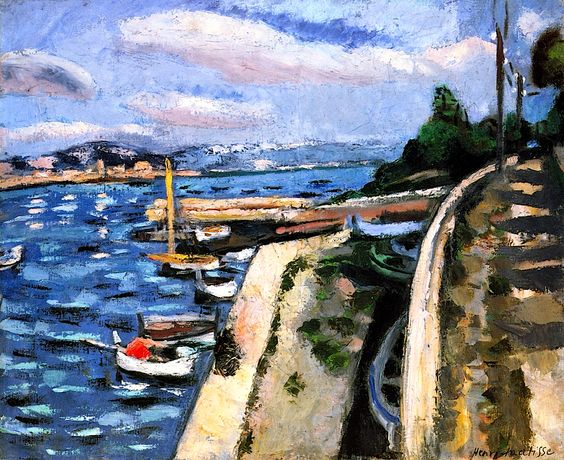

Henri Matisse’s “View of Antibes” (1925) offers a radiant glimpse of the Riviera at a moment when the artist’s Nice period was in full stride. The canvas looks outward from the curve of a sea wall toward a small harbor filled with bobbing boats, a bright jetty extending into the water, and distant headlands dissolving into layered blues. Everything in the scene—stones, surf, rigging, shadows, clouds—has been simplified and tuned into an orchestration of color and rhythm. Rather than presenting a topographical record of Antibes, Matisse creates a visual chord that conveys the town’s maritime spirit while revealing his mature belief that harmony arises from relations carefully set across a shallow, breathing plane.

The Riviera As Studio

Matisse’s Nice years are best known for interiors and odalisques, yet he frequently turned his attention outward to the coast. “View of Antibes” is the sea-side counterpart to those patterned rooms. Where wallpaper and drapery once supplied repeating motifs, the Mediterranean gives him parallel ripples of water, tiled strokes of light, and the long, curving line of the promenade wall. The Riviera becomes a studio without a ceiling: a controllable set of relationships rather than a landscape that dictates realism. This approach allows Matisse to pursue the same serenity and measure he sought indoors while keeping the liveliness of air and light.

Composition And The Curve That Conducts

The composition is built on a strong curve that sweeps from the bottom right corner along the sea wall and up toward the top edge. This arc is the painting’s conductor. It guides the eye past moored boats, around the harbor, and into far distances, then returns it to the foreground. Against that curve, Matisse places stabilizing horizontals: the line of the jetty, the distant horizon of the sea, and the soft band of clouds. Short, vertical accents—the mast of a boat, a post along the wall—keep the rhythm from becoming languid. The interplay of sweeping curve and measured horizontals gives the scene its controlled motion: the sense of slow tidal circulation rather than dramatic surge.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

Although the view promises depth, Matisse keeps space shallow and legible. The sea wall presses forward like a painted stripe; the water is a patterned plane; the distant promontory is an interlocking block of blues and mauves. Overlaps and changes in scale supply just enough depth for the eye to navigate, but the surface remains emphatically pictorial. This productive flatness allows water, land, and architecture to interact as colored shapes that hold the canvas together. The viewer experiences both a believable harbor and a decorative field whose pleasures are on the surface.

Color As Temperature And Architecture

Color is the true structure of the painting. The water is a chorus of blues—indigo, cobalt, ultramarine—broken by white and turquoise strokes that flicker like reflected sun. The sea wall is a warm chord of pale creams and ochres with gray-green shadows, against which a few decisive blacks draw the edge. The jetty and the moored craft introduce small, saturated accents—yellows, reds, cut pieces of orange—that are placed not to describe specific boats so much as to enliven the field. The distant landmass is handled in soft blue-violet, cool enough to recede but harmonized with the sea. Above, a sky of milky blues carries thin, rose-tinted clouds that repeat the warmth of the wall in a higher register. The palette is coastal without being literal, tuned to balance hot and cool across the painting’s curve.

Drawing, Contour, And The Breathing Edge

Matisse’s drawing is economical and decisive. The sea wall is a single long contour that thickens and thins as it turns, giving the stone its rounded weight. The boats are boats because a few essential lines—hull curve, stern notch, mast—are placed exactly where the eye expects them. Clouds are slung across the sky with soft-edged arcs that barely separate from blue. In each case, line functions like phrasing in music: it shapes a passage, articulates a pause, and sets a tempo without overexplaining. The result is an image that feels both constructed and spontaneous, as if the edges were discovered in the act of looking.

Water As Pattern And Motion

The surface of the sea is built from strokes that are short, angled, and layered, often set at slight diagonals to catch light. These marks create a pattern that reads simultaneously as glitter and depth. In places, Matisse drags a lighter brush over darker blue, letting bristles separate so that wet-on-dry paint breaks into bright threads. Elsewhere, he drops fat notes of white to indicate foam or sun-flash. The boats, set into this field, appear to bob because the water around them is restless. This treatment turns the Mediterranean into what it felt like to Matisse: a panel of living color that never stops shifting but remains legible as a single substance.

Architecture, Wall, And The Human Trace

The harbor wall is both architecture and walkway, a human trace that embraces the sea. Its long curve introduces a sense of security—a man-made order layered onto the natural rhythms of waves. Matisse suggests the wall’s construction with economically placed bricks of color: pale planes for sun-struck upper surfaces, slightly greener grays for damp shadow, and thin dark lines for structural joints. At the far right, poles or lampposts stride into the distance like a vanishing procession, adding a measured beat to the curve. This built presence reminds us that Antibes is not merely scenery; it is a working place where people move, moor, and make connections.

Sky, Clouds, And The Breath Of Distance

The sky is treated with the same measured simplicity. Matisse lays in a cool blue streaked with soft rose and gray, letting the clouds carry the warm echo of the sea wall into the upper register of the painting. The shape of the clouds rhymes with the curving harbor; they slip from left to right in a gentle counter-sweep. This upper band contributes air without pulling attention away from the harbor. It offers the viewer a place to rest before re-entering the orchestration below.

Boats As Accents And Actors

Each boat is an accent and an actor in the painting’s drama. Some are rendered as white hulls with a quick dark line; others carry small notes of red or yellow that ping against the blues. The boat with a red flourish near the lower left draws the eye, acting as a pivot on the water’s field, but Matisse resists making it a protagonist. These vessels are part of the rhythm, not sentimental portraits. Their variety of scale and angle keeps the harbor lively while affirming the overall design.

Brushwork, Material Presence, And Evidence Of Process

The surface of “View of Antibes” retains the vitality of its making. Paint is laid thickly in places—along the wall’s sunlit edge, in certain boat highlights—and thinly elsewhere, where scumbled layers let earlier blues peep through. The quickness of the brush is visible in the water’s diagonal swipes and the sky’s broad, soft pulls. Occasional pentimenti—a shifted contour on the wall, a boat’s hull adjusted at the waterline—remain, giving the scene time and honesty. These traces do not disrupt calm; they deepen it by showing the decisions that shaped the final chord.

Light, Hour, And Atmosphere

The painting reads as late morning or early afternoon, an hour when the Riviera’s light is abundant but not harsh. Shadows are cool, never black; color is saturated yet breathable. The atmosphere is crystalline, but Matisse avoids descriptive fuss—no tiny glitters or hard glints. Light is embedded in the palette rather than laid on top as a special effect. The viewer senses heat radiating from stone and a breeze running across the bay, but both are conveyed through color relationships, not meteorological detail.

Relation To Fauvism And To Classic Calm

“View of Antibes” inherits the Fauvist liberation of color while tempering it with Nice-period poise. The water’s intense blues and the freely brushed clouds recall the early experiments of 1905–06, yet the present painting’s intervals are measured, its conflicts reconciled. This is not shock color; it is a tuned chord. The curve of the sea wall, the gentle horizon, and the well-placed accents establish a modern classicism that can house vibrant sensation without letting it spill into chaos.

Sense Of Place Without Anecdote

Matisse avoids anecdotal description—the names of boats, the clothes of figures on the promenade, the signage of harbor life. Yet Antibes is unmistakable in spirit: a fortified curve meeting an open bay, a small fleet tugged at by wind and tide, distant landforms stepping back in blue. The omission of anecdote is a strategy to keep attention on relations. Every specific detail he chooses to exclude becomes energy available for the composition’s harmony, which in turn communicates the place more memorably than any inventory could.

Movement And The Time Of Looking

The painting choreographs how the viewer moves. The eye begins on the bright foreshortened wall at the bottom right, rides the curve to the boats, reaches the jetty, leaps to the horizon, glances at the rose cloud, and returns by way of the distant headland to the start. That loop is the painting’s tempo—neither hurried nor languid. It is akin to a promenade: a measured walk along the water during which one notices small variations in wind, light, and surface. Matisse offers a memory of that walk held still on the canvas.

The Ethics Of Attention

What shines through “View of Antibes” is an ethics of attention. The image is not about spectacle; it is about care in placement and nuance in tone. The curve is held; the colors are tuned; the accents are sparing; the touch is present but not showy. The harbor becomes a lesson in how looking can produce well-being. This is the Nice period’s ambition in a maritime key: to show that calm is not emptiness but a structure achieved by respecting relations.

Why The Painting Endures

The painting endures because its pleasures are structural and renewable. Each return to the image yields a new hinge: a soft violet in the distant promontory answering a gray in the wall’s shadow; a diagonal slash of white wake echoing a cloud’s bright edge; a tiny red accent on a boat balancing the warm pulse of the sea wall; a broken, bristled stroke of blue that both describes water and insists on paint. “View of Antibes” offers an inexhaustible loop of recognition in which the viewer alternately inhabits a harbor and reads a modern composition.

Conclusion

In “View of Antibes,” Matisse extends the decorative intelligence of his interiors to the open air. The curve of a wall takes the place of a patterned screen; the sea becomes a living textile of blues; boats and jetty provide accents comparable to vases and instruments on a table. What emerges is a serene, modern statement about balance—between hot and cool, curve and horizon, motion and rest. The painting is not a postcard; it is a structure of feeling in which the Mediterranean’s clarity is rendered as a measured chord on a luminous surface. It invites the viewer to breathe at its tempo, to follow the harbor’s loop with patient eyes, and to discover in that movement a durable sense of harmony.