Image source: wikiart.org

A Face That Arrives Like Weather

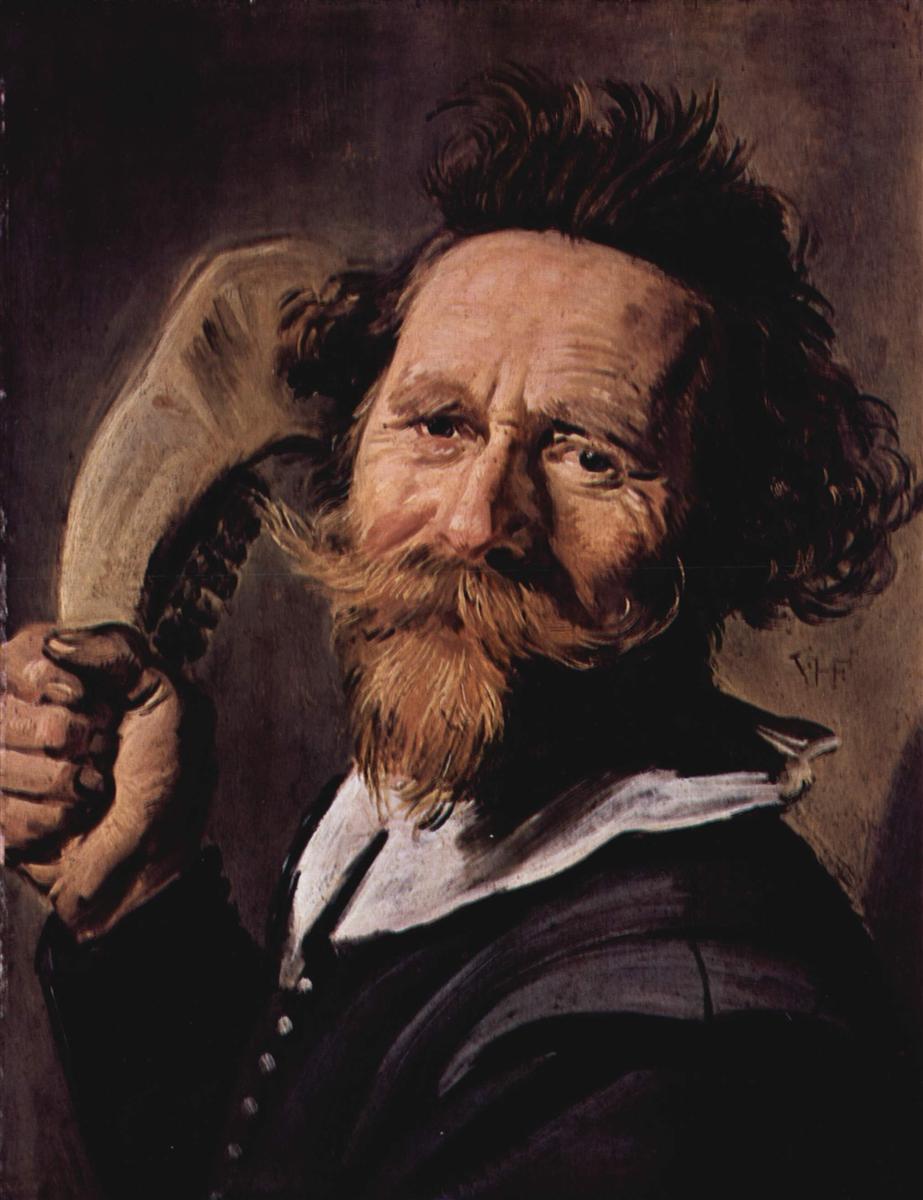

Frans Hals’s Verdonck (1627) feels less like a posed portrait and more like a sudden change in the room. The sitter turns toward us with a bracing directness, his head angled, his eyes bright and slightly narrowed, as if he has just stepped into the light and is measuring whoever stands before him. The effect is immediate and physical. Hals makes the painted surface behave like a threshold, and the man on the other side of it feels close enough to speak.

What strikes first is the collision of opposites. The expression carries a hint of roughness, a lived-in creasing around the eyes, the kind of face that seems shaped by outdoors air and strong opinions. Yet the gaze is controlled, almost appraising, with a steady intelligence behind it. Hals often paints sitters who appear caught in a moment between stillness and motion, and here that moment is charged, as if the sitter is mid-turn, half engaged with someone off to the side, half deciding how to meet us.

The portrait is also unusual in how it handles theatricality. There is no elaborate interior, no background story, no decorative clutter. Instead, the drama is concentrated into three elements: the face, the gesture, and the formidable curved blade held up near the head. In Hals’s hands, that blade is not simply an object. It becomes a visual amplifier, a prop that sharpens the sitter’s presence and turns the encounter into a test of nerve.

The Turn of the Body and the Trap of the Cropping

Hals builds intensity through cropping and rotation. The sitter is pushed close to the picture plane, cut off at the shoulders and chest, leaving no comfortable distance. The body twists away while the head turns back, creating a spiral that feels active, not arranged. This twist is one of Hals’s most effective strategies because it implies interruption. Something has happened. Someone has spoken. The sitter has responded.

The background is plain and dark, but not empty. It is a worked field of paint, a shallow space that holds the figure without explaining him. This emptiness forces the viewer to focus on the human signal of the face, and it also makes the weapon read more starkly. With no surrounding details to soften its presence, the blade becomes part of the portrait’s grammar of immediacy.

Cropping also magnifies the psychological stakes. In a full-length portrait, the viewer can read posture, costume, and setting as a social argument. Here, Hals denies us those comforts. We are given a close encounter with a man who looks as if he has been caught mid-gesture. The closeness makes the gaze feel personal and slightly confrontational, not in a hostile way, but in a way that insists on attention.

The twist of the body is reinforced by the diagonal of the raised arm and the angled blade. Those diagonals slice through the composition, turning the portrait into a web of directional forces. The viewer’s eye is pulled from the hand to the weapon to the face, then back to the eyes, repeating the circuit. Hals uses structure to create a rhythm that feels like a heartbeat.

The Curved Blade as Prop and Signal

The raised blade is the portrait’s most dramatic feature, and it is important to read it as both literal and symbolic. It suggests a martial identity or at least an association with readiness and strength. It may evoke a soldier, a guard, or a figure who performs toughness as part of his public role. In Dutch painting of the period, weapons could function as markers of civic service or masculine authority, especially in contexts connected to militias and civic pride.

Yet Hals also treats the blade as a compositional device. Its curve echoes the roundness of the sitter’s hair and the arc of the raised elbow. The weapon becomes a sweeping shape that frames the head and intensifies the turn of the face. It is less a threat than a graphic flourish, a bold mark that adds to the portrait’s sense of motion.

The blade’s pale surface catches light, creating a bright counterpoint to the darker background. This contrast makes it read immediately, and it also helps balance the portrait, preventing the face from becoming the only point of brightness. Hals is careful in how he distributes light, placing highlights where the painting needs emphasis: forehead, cheekbones, moustache, collar, and the weapon’s edge.

At the same time, the blade introduces ambiguity. Is the sitter presenting it proudly, as a sign of profession or personal flair, or is Hals borrowing the object to build a character study that borders on theatrical role playing? Hals often enjoyed the edge between true portrait and expressive type. In Verdonck, the weapon pushes the painting toward performance, but the gaze pulls it back toward individuality. The tension between those two readings gives the portrait its bite.

Hair, Moustache, and the Wildness of Identity

One of the portrait’s pleasures is the sitter’s hair. It erupts upward and outward in unruly masses, giving the head a stormy silhouette. Hals paints this hair not as a tidy hairstyle but as a living texture. The strokes are quick and directional, suggesting strands and clumps rather than counting every detail. The effect is energetic and slightly untamed, as if the sitter has stepped in from wind or exertion.

The moustache is equally expressive. It is thick, curled, and emphatic, almost a personality in itself. Hals uses the moustache as a tool for character. It frames the mouth and shapes the expression, turning what could be a simple gaze into something more complicated: amused, skeptical, hardened, or playful. The moustache also creates a strong horizontal element across the face, stabilizing the composition against the vertical rise of the hair.

The beard, lighter and more ragged, catches highlights in a way that makes it feel tactile. Hals’s touch is confident. He suggests individual hairs with swift strokes, then steps back into broader masses. This combination of specificity and suggestion gives the facial hair weight without fussiness.

These features create an impression of a man who is not polished into courtly elegance. He is expressive, slightly rough, and proud of it. Hals does not attempt to smooth him into an ideal. Instead, he makes the sitter’s particularity the source of authority.

The Eyes and the Psychology of Being Met

The eyes do most of the portrait’s emotional work. They are directed toward the viewer with a frankness that feels immediate. Hals paints the gaze as active, not simply present. The eyelids and brow suggest a subtle narrowing, the look of someone assessing rather than merely posing.

This assessment changes how the viewer behaves. Many portraits allow us to look without feeling looked at. Hals does the opposite. He makes the sitter’s gaze responsive, creating the sensation that the portrait is aware of our attention. This creates a relationship rather than a one-way viewing.

The slight asymmetry of the expression adds to this. The mouth does not settle into a neutral line. It hints at a half-smile or a knowing tension, as if the sitter is about to speak. That ambiguity keeps the portrait from becoming a simple statement of toughness. We can read humor here, perhaps even a kind of mischievous confidence.

Hals’s genius is that he does not define the emotion too narrowly. The sitter can be read as proud, amused, wary, or simply alert. The portrait remains open enough for the viewer’s experience to shape it, which is part of why Hals’s faces feel perpetually alive.

Light, Shadow, and the Sculpting of a Rough Face

The lighting is strong and directional, carving the face with clear highlights and deep shadows. Hals uses this contrast to emphasize texture: the creases at the forehead, the planes of the cheeks, the ridge of the nose, the softness of the moustache. The face feels sculpted by light, as if it has been weathered into shape.

The shadow side of the face is not dead. It holds warm undertones, suggesting blood and flesh beneath the darkness. Hals avoids the trap of turning shadow into flat brown. Instead, he lets it breathe with subtle color variation. This gives the face a physical presence, a sense of volume that feels immediate even at a glance.

The collar and shirt are painted with broad, confident strokes, bright but not pristine. The fabric reads as lived-in, slightly softened, more practical than ceremonial. That practicality harmonizes with the sitter’s overall impression. This is not a portrait of immaculate courtliness. It is a portrait of forceful presence.

The background remains subdued so the lighting can do its work. By keeping the space behind the sitter simple, Hals makes the light feel more concentrated, as if it is spotlighting the encounter. The portrait becomes a stage with one actor, fully illuminated where it matters.

Color and the Portrait’s Earthy Heat

The palette is warm and earthy. Browns, deep purples, and muted blacks create a dark atmosphere, while flesh tones and the pale weapon introduce brighter notes. The warmth of the skin is especially important. Hals paints the face with reds and ochres that suggest vitality, a pulse beneath the surface.

This warmth helps prevent the portrait from feeling merely severe. Even with the blade and the intense gaze, the face remains human and approachable. The skin is not idealized into smooth perfection. It shows texture, and that texture is part of the portrait’s honesty.

The hair and moustache carry warm highlights, especially around the beard where light catches the edges. This creates a halo-like effect around the lower face, not a religious halo, but a painterly one that draws attention to the mouth and expression.

The weapon’s pale tone is a compositional counterweight. It breaks the darkness and gives the painting a bold graphic element. In a restrained palette, a single bright object can dominate, and Hals embraces that dominance to heighten drama.

Brushwork as Character, Not Decoration

Hals’s brushwork is not merely a stylistic signature. It is the mechanism by which the portrait becomes alive. The strokes in the hair are fast and directional, creating the sense of movement and volume. The strokes in the face are layered, building form through shifts in tone rather than through tight outlines.

This approach gives the portrait a vibrating quality. From a distance, the image coheres into a convincing presence. Up close, it dissolves into marks, as if the painter’s hand is still visible in the moment of creation. That oscillation between illusion and paint is part of Hals’s power. He lets us see both the person and the act of painting the person.

The weapon is handled with broad confidence. Hals suggests its surface and edge without turning it into a polished still life. The point is not the object’s precise material description. The point is how it behaves in light and how it contributes to the sitter’s presence.

The clothing is painted with economy. Hals indicates structure and shadow, but he does not linger on decorative detail. This keeps attention on the face and gesture, where the portrait’s psychological energy lives.

Portrait, Character Study, and the Edge of Performance

Verdonck sits on the boundary between portrait and character study. The specificity of the face suggests an individual, yet the dramatic prop and the close theatrical staging evoke the world of expressive types. Hals often painted figures who feel like they could be someone specific and also someone symbolic, an embodiment of cheer, swagger, skepticism, or bravado.

This ambiguity is not a weakness. It is a source of richness. If the painting is a portrait of a particular man, the weapon and wild hair may reflect personal identity, a public role, or a chosen self-image. If it is a character study, then Hals is using the figure to explore how expression, costume, and gesture can create a vivid human impression.

In either case, the painting is about presence. Hals is less interested in telling us a biography than in making the sitter feel near. The viewer does not walk away with facts. The viewer walks away with the sensation of having met someone.

That sensation is intensified by the sitter’s confidence. The raised arm and the turned head create a posture that feels self-possessed. He does not look like someone who is being displayed. He looks like someone who is choosing to be seen.

The Viewer’s Role in the Painting’s Drama

Hals designs the portrait so the viewer becomes part of the event. The sitter’s gaze addresses us directly. The turn of the head implies we have arrived or spoken. The raised weapon suggests a moment of display, perhaps a playful showing-off, perhaps a sign of readiness. The portrait does not define our role, which makes the encounter feel open and slightly unpredictable.

This unpredictability is one reason Hals’s lively portraits remain compelling. They behave like conversations, not monuments. The painting feels capable of change, as if the sitter’s expression could shift in the next second, the arm could lower, the head could turn away.

The portrait also plays with intimidation and charm. The blade could suggest danger, but the face carries warmth and intelligence. The sitter looks fierce in silhouette, yet human in detail. Hals keeps both readings alive, which creates an emotional complexity that rewards repeated viewing.

The result is a portrait that engages the viewer’s instincts. You do not simply analyze it. You react to it. You feel its energy before you name it.

Frans Hals in 1627 and the Confidence of Risk

By 1627, Hals’s style had matured into a language of boldness and immediacy. He had the confidence to paint faces that were not polished into ideal calm, and he had the skill to make fleeting expression feel stable enough to last. Verdonck shows that confidence in how unapologetically vivid it is.

The portrait is risky because it depends on immediacy. If the gaze were slightly wrong, the expression could collapse into caricature. If the weapon were painted too literally, it could distract from the face. If the brushwork were too loose, the image could lose coherence. Hals balances all of these dangers. He keeps the expression believable, the composition tight, and the paint alive.

This balancing act is what makes the portrait feel modern. It values presence over polish. It trusts the viewer to complete the illusion, to step back and let the marks cohere into life. Hals paints not only what the sitter looks like, but how the sitter registers as a force in space.

Conclusion: A Portrait That Holds Its Ground

Verdonck (1627) is a portrait that confronts and charms in the same breath. Through a twisting pose, a vivid gaze, unruly hair, and the dramatic curve of a raised blade, Frans Hals creates an image that feels like an encounter rather than a static record. The painting’s power comes from its compression. There is no elaborate setting to soften the impact. Everything is concentrated into face, gesture, and light.

Hals makes the sitter feel independent and self-possessed. He meets the viewer without apology, and he remains emotionally complex, capable of warmth and severity at once. The brushwork keeps the surface alive, and the composition keeps the drama tight. The result is a work that does not simply depict a man. It stages presence, turning paint into a living exchange that still feels immediate centuries later.